The story of a remarkable Hindu temple in Pretoria's inner city

Built by Tamil immigrants almost 100 years ago, the temple has survived apartheid and urban decay to remain at the heart of its community.

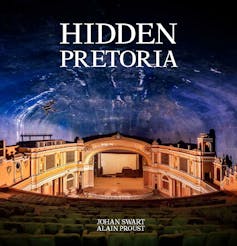

Apart from Pretoria’s legacy of grand institutional buildings, South Africa’s capital city and historical seat of the apartheid government, also contains some unique architectural masterpieces that have been built and cared for by various religious communities. These buildings reflect the stories, traditions and resilience of diverse community groups. Also made visible are the precarious conditions that have threatened the conservation of these special places over time. And the continuous efforts of community groups to preserve their buildings and their cultural identities. A number of these sites have recently been documented by architect Johan Swart and photographer Alain Proust in a publication called Hidden Pretoria. This is an edited extract from the book.

Among a variety of remarkable religious buildings in Pretoria’s inner city are the likes of the iconic Gereformeerde Kerk Pretoria (or Paul Kruger Church), built by the republican founding fathers of the city in the late 1800s, still utilised today by a small Dutch Reformed congregation for Sunday services. The busy Queen Street Mosque, on the other hand, is hidden among the densely packed high-rise buildings of a city block. Abandoned in the inner city is also the Old Synagogue, the early home of Pretoria’s Jewish community that was later appropriated by the apartheid state to house the treason trial of Nelson Mandela and his co-accused. Perhaps the most remarkable of the religious sites, though, is the Mariamman Temple, the home of Pretoria’s Tamil League and located in the historical and turbulent suburb of Marabastad.

The Mariamman Temple

The Mariamman Temple is a small complex of buildings constructed from 1928 onwards within the fine urban grain of the Asiatic Bazaar. This is a historical part of Marabastad that managed to survive apartheid-era clearances in the area. A visible landmark is the gopuram or entrance portal on 6th Street, considered the most impressive of its kind in South Africa. Especially since its renovation in the early 1990s and the subsequent reintroduction of colour and detail by the Tamil community.

Groups from India arrived in the Natal Colony on South Africa’s east coast as indentured labourers as early as the 1860s, and settled in the Pretoria region in central Sough Africa from the 1880s onwards.

After its establishment in the early 1890s, the Asiatic Bazaar became home to most of Pretoria’s Indian communities. The Tamil-speaking Hindu community founded the Pretoria Tamil League here in the early 20th century. They developed the temple complex as the heart of their community life and still act as custodians.

Marabastad developed in parallel to the ‘white’ inner city as a mixed-race precinct. But, as with other ‘non-white’ suburbs it fell victim to demolitions and forced removals of the apartheid-era government in their enforcement of racial segration as dictated by legislation such as the Slum Clearance Act of 1934 and the Group Areas Act of 1950.

Over time, the residents of Marabastad were moved to areas designated for various groups which apartheid defined by race and colour. These included Atteridgeville, Eersterust and Laudium. The Asiatic Bazaar, however, was left intact as a non-residential trading area. Historical landmarks such as the Mariamman Temple, Ismaili Mosque and the Orient Cinema have survived to the present.

Harmony with the cosmos

Replacing an earlier structure of wood and iron, the first phase of the current temple was planned around 1928 and constructed in phases. First the sacred elements were erected, the cella (inner area) and arda mandapam (pavilion) which were built according to strict proportional systems. Then the maha (large) mandapam was added to accommodate spiritual gatherings. Lastly, the gopuram was completed in 1938 as the main architectural feature.

The temple was dedicated to the goddess Mariamman. It was built in the south Indian Dravida Style known for its large tiered gopurams (entrance portals) and the close integration of temples and their urban surroundings. Research has shown that the designers, P Govender and G Krishnan, followed strict design norms derived from guidelines or precedent. The building can be seen as a textbook example, achieving its intended mathematical harmony with the cosmos.

Restoration

The Tamil community built a new temple when they were relocated to Laudium. But the Mariamman Temple remained in use, even as parts of the building fell into disrepair. In the early 1990s, an academically researched restoration was executed by architects Schalk le Roux and Nico Botes. They worked in close partnership with the Tamil community who actively contributed to the research and design processes.

A new navakaragam was added while the gopuram structure was repaired and its external tiers returned to their colourful appearance. This prompted the community to commission new murtis (figurative sculptures) which were made by artisans from India and installed over time, a clear sign of continued care and ownership.

Marabastad has declined over the decades and the area seems to be stuck in a development impasse. But, within this context, the Mariamman Temple can be seen as a remarkable success story.

The complex is evidence of the close interaction between architecture and social practices, and the restoration project has shown that architectural conservation is most sustainably done in partnership with communities.

Marabastad is a significant historical area in desperate need of more projects that will contribute to its renewal as a living neighbourhood.

You can order a copy of Hidden Pretoria here.

Johan Swart does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.