NHS plan to share GP patient data postponed – but will new measures address concerns?

The latest NHS data sharing scheme looked set to repeat past mistakes – but the latest postponement provides hope.

July 27, 2021 • 8 min • Source

The UK government has postponed its controversial GP patient data gathering scheme in response to concerns over privacy. The General Practice Data for Planning and Research (GPDPR) scheme had planned to upload the data of England’s 61 million NHS users, in a “pseudonymised” form, to a central database. That database could then be accessed by institutions to advance health research and planning.

GPDPR was heavily criticised for being rushed through without patients being properly informed. The pseudonymised form (with obviously identifiable information removed) in which the patient data would enter the database was also challenged, with researchers pointing out that it did not do enough to guarantee patient privacy.

The government has laid out a series of significant improvements to the data-sharing scheme which will now be carried out before its eventual implementation. But while these proposed changes are welcome, the future of health data in the UK, after years of wrangling and U-turns, is yet to be free of controversy.

The pandemic has called for the productive use of detailed health data, held in the UK by the NHS in a variety of specialised databases. Such data has been used in the OpenSAFELY environment at the University of Oxford, which produced early insights into factors associated with COVID-related deaths without compromising patient privacy.

It’s less clear whether the UK government’s own initiatives were productive, let alone responsible. A comprehensive list of the data sets included in the COVID data store, built by big data company Palantir, was never published. We’re still in the dark about what AI company Faculty and others actually used it for. Meanwhile, stories abounded about senior NHS and government officials talking to tech companies about the sale of NHS data.

Previous data-sharing plans

Then, in spring 2021, the UK government decided to revive a dormant plan. For much of 2013 and 2014, the then-health secretary, Jeremy Hunt, and his team at NHS England had attempted to introduce the “care.data” scheme. This would have gathered GP data from all English GPs, combining it with health databases held by the health service’s IT agency, NHS Digital, to create a large data set for a vaguely defined set of purposes.

The plan was thought to be reckless. There was a backlash from GPs and the wider public, with the press raking up stories of past dubious NHS health data sales. This forced the introduction of opt-outs, definite and indefinite postponements, and eventually the abandonment of care.data in 2016.

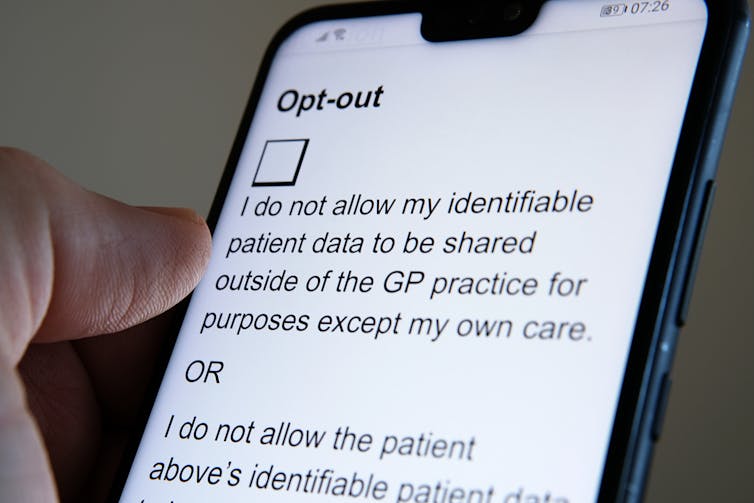

This chaos seemed to be repeating itself in 2021, and at a very high speed. The GPDPR scheme was announced on May 12 2021, catching GPs and the public by surprise. The advocacy group medConfidential quickly unearthed a way for patients to opt out of the scheme, with GPs providing information to help them do so.

The scheme was postponed on June 8 by a few months after objections were raised by various medical associations and the MP David Davis. Meanwhile, health researchers expressed their displeasure at privacy concerns preventing data collection that could one day be used to save lives. So far, this was all very 2014.

But at the end of July 2021, we appear to have reached a point where the officials behind the GPDPR scheme are finally listening to critics’ concerns. We may no longer be headed for a repeat of the complete failure of care.data.

Proposed improvements

GPDPR has now been postponed again until a collection of serious mitigations are put in place. In my view, as a researcher of health data and cybersecurity, the most important of these is that GP data, once uploaded, will only be made available in TREs (trusted research environments) similar to the OpenSAFELY one mentioned above. This means a move from sharing data in a “safe” way to sharing access to data in a way that is verifiably safe through monitoring and transparency.

Much of the care.data debate concerned the safety and legal status of “pseudonymised” data. Individual level health data is considered too rich to be safely anonymised, jeopardising patient privacy. Accessing data sets only within TREs mitigates this issue, and also the problem of data sets being shared onward.

TREs also provide a unique opportunity for transparency. All queries executed against the data can be recorded and monitored – OpenSAFELY even publishes them. This will make it easier to guarantee the welcome promise that the GP data will only be used for improving health and care.

It was clear already that both GPs and NHS Digital, will be legally required to produce data protection impact assessments for the scheme. These will now be published well ahead of the data collection, offering a great opportunity for transparency, consultation and scrutiny.

Another mitigation concerns GPDPR opt-outs, which were initially only intended to apply to data not yet uploaded to the new database. This was in contradiction, at least in spirit, with data protection rights on withdrawing consent and requesting data deletion. The option to opt out of the GPDPR scheme has now been extended for at least another year. Finally, the government has promised better communication to the public before the scheme goes ahead.

An end to the controversy?

Overall, these new measures provide hope. But some concerns remain. First, many of the concerns expressed about GP data also apply to hospital data, which is currently widely shared in pseudonymised form, including for purposes that many would consider commercial. This, and a range of other forms of sharing, make it hard to take the government’s line, “patient data is not for sale and never will be”, entirely seriously.

If the government was serious about protecting health data, it would ensure that hospital data, genomic data, and other centralised databases were also only available through TREs, and only accessible for the purpose of improving health and care.

More generally, the current UK government continues to put forward a narrative of commercialisation and innovation, demanding de-regulation where necessary. In particular, the government’s promises sit awkwardly with the emphasis on innovation in its health data sharing strategy. With these tensions still to be resolved, and a new health and care bill likely to be rushed through shortly, the future of health data in the UK is still highly uncertain.

Eerke Boiten receives funding from various research funding organisations for research projects that are not closely related to the topic of this article.