To control bedbugs, tell potential tenants about past infestations, study says

It might seem crazy for landlords to tell potential tenants about past bedbug infestations, but Alison Hill believes it will pay off in the long run. In a study, Hill found that while landlords would see a modest drop in rental income in the short term, they would make that money back in a handful of years, and the policies could dramatically slow the spread of the insects.

Pretty much anybody who’s been apartment hunting knows what they’re looking for in a place to live, and bedbugs usually aren’t on that list.

So it might seem like a crazy idea for landlords to tell potential tenants about past bedbug infestations, but Alison Hill believes it will pay off in the long run.

A John Harvard Distinguished Science Fellow, Hill is the co-author of a study that examines a requirement — proposed in a number of cities across the country — that would mandate such notifications. The results show that while landlords would experience a modest drop in rental income in the short term, they would make that money back in just a handful of years, and that the policy could dramatically slow the spread of the insects. The study is described in a paper published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

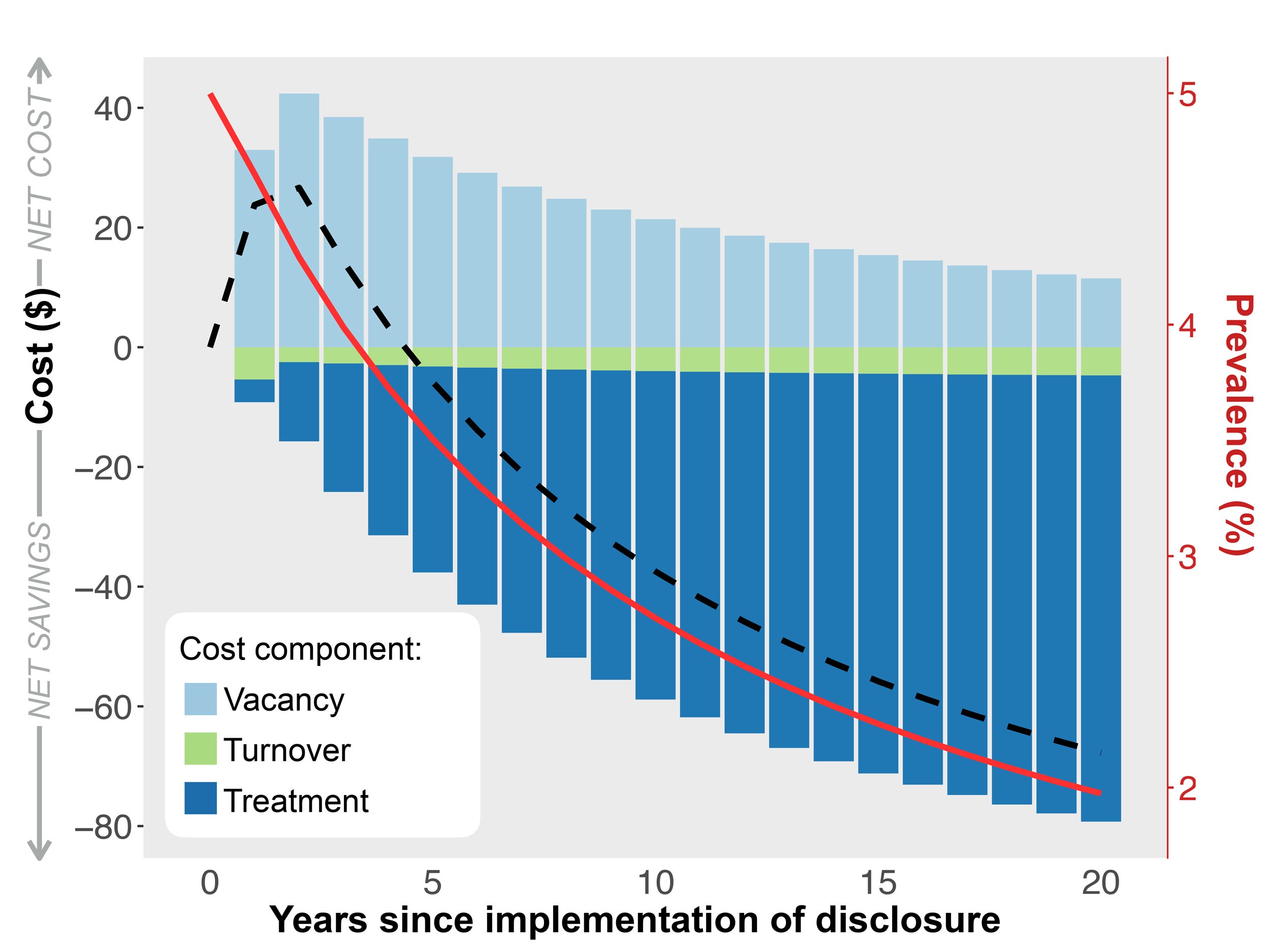

“We find that in most cases, these policies are expected to have some costs to landlords in the first few years after they are enacted,” Hill said. “There will be some lost rent and higher vacancies rates in apartments that have a history of infestation. But those costs all come back as gains later, because we find that these policies are effective at reducing the spread of infestations.”

One way the bugs can spread, Hill said, is during moves. Tenants relocating from infested apartments may inadvertently bring bedbugs to their new place as well as leave them behind at their old one, since the bugs can live in walls and floors as well as in furniture.

The proposed disclosure policy creates an unofficial quarantine period, Hill said, by reducing the chances that an infested unit is rented, allowing landlords time to thoroughly treat the space for bedbugs and decreasing the chances they’ll continue spreading.

“When the overall level of bedbugs decreases,” Hill said, “landlords will spend less on costly pest-control efforts. There is less chance their apartments will be infested, and vacancy rates go back to normal. While for the first few years we predict there is a little extra cost to them — it depends on the rental market, but it’s on the order of 0.2 percent to 2 percent per unit per year — after the five-year mark they’re expected to see gains that are even higher than that.”

The study’s first author, Sherrie Xie, a Ph.D. candidate and veterinary medicine student at the University of Pennsylvania, also developed an online tool to demonstrate how the policy can lead to savings for landlords over time.

While landlords who notify tenants of past bedbug infestations would experience a modest drop in rental income in the short term, they would make that money back in just a handful of years, according to the study.

Courtesy of Alison Hill

While landlords who notify tenants of past bedbug infestations would experience a modest drop in rental income in the short term, they would make that money back in just a handful of years, according to the study.

Courtesy of Alison Hill

The study was sparked, Hill said, by the fact that the re-emergence of bedbugs in recent decades doesn’t fall squarely to any particular governmental agency.

“I’m a public health researcher,” she said. “I study infectious diseases like HIV and how we can control them, so to me bedbugs seem like an issue for public health agencies. But at the same time, it’s a problem that’s related to housing … so maybe people who deal with mice, rats, and cockroaches should be the ones dealing with them.

“But the reality is that in many cities there is not really any agency responsible for bedbugs,” she continued. “So it’s basically a private thing that people have to deal with.”

While that uncertainty has created problems for cities struggling to deal with bedbug outbreaks, it has also created a vacuum for research.

“There’s no government funding agency that’s tasked with funding research on bedbugs,” Hill said. “Which just means there are a lot of unknowns about dealing with bedbugs.”

In an effort to fill that vacuum, the National Science Foundation funded a working group made up of experts from a host of disciplines, including epidemiology, urban planning, economics, and entomology. The group was co-chaired by Michael Levy, an associate professor of epidemiology at the University of Pennsylvania, who initiated the study and is its senior author.

Based on her experience modeling infectious-disease transmission, Hill was invited to join the panel with an eye toward developing models that could make predictions about how best to control the spread of the insects. Another recruit to the team was Chris Rehmann, a professor of civil engineering at Iowa State University, who co-authored the study with Hill, Xie, and Levy.

Going forward, Hill said, researchers are planning to expand the study to incorporate greater variety in the housing market and understand how various policies can drive rents up or down, while other studies are in the works that would examine how bedbugs spread from location to location using data on the bug’s genetics or the relocation patterns of a city’s residents.

Other studies are planned that would focus on the mental health and economic effects of bedbug infestations on residents, she said.

In the meantime, Hill’s co-authors are planning to present their findings to city officials in Philadelphia, where notification requirements are under consideration.

“Our hope is to spread the word that disclosure policies can be a cost-effective way of slowing bedbug spread,” she said, “because while there are a handful of cities that have implemented these policies, many others haven’t. We hope our study provides some extra evidence to help make that decision.”

This research was supported with funding from the National Science Foundation (via the National Socio-Environmental Synthesis Center), the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health.