1930_United_States_Senate_election_in_Illinois

The 1930 United States Senate election in Illinois took place on November 4, 1930.[1]

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

Results by county Lewis: 40–50% 50–60% 60–70% 70–80% 80–90% Hanna McCormick: 40–50% 50–60% | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

Incumbent Republican Charles S. Deneen was unseated in the Republican Party's primary election. Democrat J. Hamilton Lewis, who previously held this Senate seat from 1913 to 1919, won a second nonconsecutive term.

This election was notable as being the first instance in which a major party nominated a female candidate for United States Senate, with Ruth Hanna McCormick, widow of Deneen's predecessor in this seat Medill McCormick, becoming the Republican nominee after defeating Deneen in the Republican party’s primary election.

This was the first time since the Seventeenth Amendment to the United States Constitution made U.S. senators popularly elected that a Democrat won a U.S. Senate election in the state of Illinois.

The primaries and general election coincided with those for House and those for state elections.[1] The primaries were held April 8, 1930.[1]

Background

The U.S. Senate seat in question was held by Democrat J. Hamilton Lewis from 1913 to 1919. He lost the seat in the 1918 election (the first year this seat faced a direct popular vote) to Republican Medill McCormick, the husband of Ruth Hanna McCormick.[2][3] Medill McCormick lost the Republican primary of the 1924 election to Charles S. Deneen. Deneen went on to win the 1924 general election. McCormick, on February 25, 1925, died in what is considered to have been a suicide (though the suicidal nature of his death was not known to the public, contemporarily), widowing Ruth Hanna McCormick. His reelection loss is believed to have contributed to his suicide.[2][4][5][6][7]

In 1927, Medill McCormick's widow, Ruth Hanna McCormick, announced a campaign for one of Illinois' at-large seats in the 1928 election for the U.S. House of Representatives.[6] Campaigning on issues such as her opposition to the World Court, her support of Prohibition, and her support of aid to farmers, she won the election.[6] She won the Republican primary in April 1928 by a nearly 100,000 vote margin-of-victory, which drew significant attention, including being featured on the cover of Time.[6] She received a larger vote share than any other Republican on the ticket in Illinois, besides presidential nominee Herbert Hoover.[8]

J. Hamilton Lewis had remained active in Democratic politics. He had been waiting for an opportunity to stage a political comeback.[5]

The Wall Street Crash of 1929 had started an economic downturn that would ultimately be known as the Great Depression.

In recent history, Republicans had dominated U.S. Senate elections in Illinois, with only Republicans having been elected to the U.S. Senate from Illinois since popular elections were adopted after the 1912 and 1913 United States Senate elections.[6] At the time, Lewis, in 1913, was the last Democrat the state had elected to the U.S. Senate.[6] Some saw the Republican primary for U.S. senate as tantamount to election in Illinois.[6]

Only one woman, Rebecca L. Felton (who served for a single day), had ever served in the U.S. Senate, and none had ever been seated by election.[9]

Candidates

- Harold M. Beach

- James H. Kirby

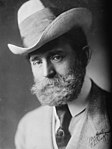

- J. Hamilton Lewis, former U.S. Senator, former Senate Majority Whip

- James O. Monroe, attorney and perennial candidate[10]

- Louis Warner

Campaign

J. Hamilton Lewis declared his candidacy on February 9, 1930.[11]

In his campaign announcement letter to the state and county Democratic committees, he claimed that he had been drafted, writing,

"I did not seek this nomination. It is well known that after I left the Senate I declined office under the Wilson Administration; equally well known that it is that I declined minority appointements [sic?] under the Harding and Coolidge Administrations. The material necessities of life have forced me to take this action. I now respond to the invitation and say that I accept."[11]

Lewis faced only token opposition in the primary, and positioned his campaign to prepare to make his opposition to prohibition the principal issue of the general election campaign.[6] In his announcement letter, he derided Prohibition as, "national tyranny".[11] He declared that he opposed enforcing temperance by law, and preferred it be done by personal will.[11] His announcement letter also advocated for greater relief to farmers.[11] His letter also blamed financial distress experienced in the city of Chicago, and in Cook County as a whole as the fault of the local Republican party.[11]

Results

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | James Hamilton Lewis | 247,420 | 75.59 | |

| Democratic | James O. Monroe | 24,390 | 7.45 | |

| Democratic | James H. Kirby | 23,014 | 7.03 | |

| Democratic | Louis Warner | 19,619 | 5.99 | |

| Democratic | Harold M. Beach | 12,868 | 3.93 | |

| Write-in | Others | 1 | 0.00 | |

| Total votes | 327,312 | 100 | ||

Candidates

- Charles S. Deneen, incumbent U.S. senator

- Ruth Hanna McCormick, U.S. congresswoman

- Adelbert McPherson, candidate for U.S. Senate in 1924[12]

- Newton Jenkins, attorney and candidate for U.S. Senate in 1924[13][14]

- Abe Lincoln Wieler

Campaign

On September 22, 1929, Ruth Hanna McCormick announced her intention to run for the Senate against Republican incumbent Charles S. Deneen, who had won the seat from her husband in 1924.[6][15] She sought the nomination at a time when no woman had ever been elected to the Senate.[16] By October, McCormick had returned to Illinois, visiting the state's various counties to rally support while Deneen was stuck in Washington, D.C., on Senate business.[17]

McCormick formally launched her campaign January 13, 1930.[6] Newton Jenkins, another challenger to Deneen, formally launched his campaign on February 10, 1930, in Aurora, Illinois.[11] Deneen did not launch his campaign until early March 1930.[6]

Both McCormick and Deneen were progressives.[6] Deneen was associated with the "reform" branch of the Republican Party, opposed to Chicago mayor William Hale Thompson.[6] McCormick wanted to also draw a district separation between herself and the Chicago and Cook County Republican political machine, especially after the Pineapple Primary of 1928.[6] She used the slogan "No favors and no bunk".[6]

As an Illinois farm owner, McCormick drew support from farmers in the state, particularly those down-state.[16] However, little attention was paid to by either McCormick or Deneen to the issue of farm cisis, as neither wanted to draw further attention to the economic crisis occurring under the watch of Republican president Herbert Hoover.[6] McCormick campaigned on issues that she felt Deneen was the weakest on, like the question of the League of Nations and World Court.[6][18] She attacked Deneen for supporting the League of Nations.[6] She questioned Deneen's commitment to supporting Prohibition, and alleged that he had ties to anti-Prohibition politicians such as Anton Cermak.[6] In turn, Deneen accused McCormick of having ties to the political machine of Chicago mayor William Hale Thompson, pointing to her embrace of her endorsement from Robert E. Crowe, an ally of Thompson's.[6] In fact, in the primary, McCormick was seen as having received the support of Thompson, who also had a rivalry with Deneen.[19]

Both Deneen and Newton Jenkins attacked McCormick for the vast amounts of wealth she was spending on the race.[6] McCormick later testified that the primary campaign cost $252,572 of her own money (equivalent to $4,606,672 in 2023), with additional funds being raised from relatives.[20] She made speaking engagements in 100 of the state's 102 counties.[6]

While she was a leading women in American politics, McCormick's campaign was not widely embraced as a feminist campaign, in part, because many women's groups resented McCormick's opposition to the League of Nations and World Court.[6]

The primary campaign attracted national interest, with two prominent figures battling each other.[6]

Results

McCormick defeated Deneen in the primary, becoming the first female major party nominee for the United States Senate.[6][18][19][21] The victory showed strong support for McCormick throughout the state, including a surprisingly strong showing in Chicago.[19]

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Ruth Hanna McCormick | 714,606 | 50.66 | |

| Republican | Charles S. Deneen (incumbent) | 496,412 | 35.19 | |

| Republican | Newton Jenkins | 161,261 | 11.43 | |

| Republican | Abe Lincoln Wisler | 19,778 | 1.40 | |

| Republican | Adelbert McPherson | 18,582 | 1.32 | |

| Total votes | 1,410,639 | 100 | ||

Candidates

- George Koop (Socialist), perennial candidate[22]

- J. Hamilton Lewis (Democratic), former U.S. senator

- Ruth Hanna McCormick (Republican), U.S. congresswoman

- James J. McGrath (Liberty)

- Lottie Holman O'Neill (independent Republican), Illinois state representative

- C. Emmet Smith (Anti-League World Court, Anti-Foreign Entanglements)

- Ernest Stout (American National)

- Freeman Thompson (Communist)

- Louis Warner (Peace and Prosperity)

Campaign

Partisan dynamics

Lewis was considered a formidable candidate, and campaigned with vigor.[5] Nevertheless, Illinois had gone Republican in all U.S. Senate elections held since U.S. senators began being popularly elected post-1912, and McCormick was therefore, at the onset of the general election, seen by many as having a partisan advantage.[6]

Contrarily, however, partisan dynamics would ultimately prove to be a factor hindering McCormick's campaign, as the 1930 elections were proved to be difficult for Republican candidates. The difficulty for Republican candidates was due to the stock market crash had occurred the year before under Republican president Herbert Hoover, and with a Republican-controlled House and Senate.[2]

Prohibition issue

One contentious issue in the general election campaign was Prohibition, which McCormick supported and Lewis did not.[18] While she supported prohibition, McCormick pledged during the general election that she would honor what voters voiced in the referendum on whether to repeal the state-level prohibition law (voters ultimately would vote to repeal by 67% to 33%, signaling significant opposition to prohibition).[1][6][23] As a result of McCormick's wavering on the issue of prohibition, the Anti-Saloon League ultimately endorsed independent candidate Lottie Holman O'Neill over McCormick.[6][21]

Despite Lottie Holman O'Neil posturing that she only entered the race to provide voters with a truly anti-prohibition candidate, the Chicago Tribune charged that, because O'Neil was a "bitter political enemy" of McCormick (she had previously made her disdain for McCormick known), her candidacy was, "a spite campaign rather than a dry campaign."[6] It was also speculated by the Tribune that she could act as a spoiler candidate, helping hand Lewis victory.[6] O'Neill ran an aggressive campaign accusing McCormick of corruption and assailing McCormick's inconsistent stance on prohibition.[6]

Scrutiny of McCormick's primary campaign spending

The high cost of McCormick's primary campaign also became a point for attack in the general election, with Lewis accusing McCormick of trying to buy the election.[21]: 198 Republican Senator Gerald Nye, chairman of the Senate Campaign Fund Investigating Committee, investigated campaign expenditures of the Republican primary.[6][18] While he stated, after a preliminary investigation, that there were no apparent discrepancies between what candidates reported to have spent, it was likely that some money spent on their behalf was not reported.[6] He drew attention to the mere $6,000 spent by McCormick in Cook County, where roughly half the voters in the primary were from, and the near $247,000 (equivalent to $4,514,163 in 2023) she spent in the rest of the state.[6] He implied that she had received help from Chicago mayor Thompson.[6] After a hostile June 14 editorial written in The New York Times , McCormick denied any links between her and mayor Thompson, declaring, "My campaign was essentially an anti-machine campaign".[6] McCormick testified before Senator Nye in hearings held in Chicago in mid-July.[6] Her four-hour testimony was well-covered by the press.[6]

Gender and sexism

Lewis made a point not to refer to McCormick by name, instead calling her "the lady candidate".[21]: 189 Hamilton referred to McCormick as a "dollar princess", and remarked, "you cannot buy a landslide nor win an Illinois senatorship by sex appeal".[24]

McCormick refused to make her gender an issue, calling gender differences a personality issue and insisting political party mattered more in the general election.[21]: 201

There was sexist backlash to McCormick's nomination.[6] For instance, Hiram Johnson, a prominent progressive, wrote of her victory in the Republican primary and prospective election, "Some of us consider it a punch in the eye to the Senate, because it means the admission of the first woman."[6][21]

McCormick's candidacy was not widely embraced as a feminist campaign, in part, because many women's groups resented McCormick's opposition to the League of Nations and World Court.[6]

William H. Thompson's support of Lewis

Republican Chicago mayor William H. Thompson, who had been seen as supporting McCormick in the Republican primary, publicly threw his support behind Lewis in the general election.[6][21]: 198 Thompson had a rivalry with the McCormick family, and also blamed the failure of his ambition of clinching the presidential nomination at the 1928 Republican National Convention as having been stymied by Ruth Hanna McCormick's failure to support him as a prospective candidate.[25] Thompson went as far as to, on October 23, 1930, print and distribute a pamphlet which accused McCormick's late husband of having made racist remarks, an attack that McCormick called, "malicious and unjustifiable".[6]

Great Depression

While neither McCormick nor Lewis treated the economic turmoil as a main issue, until the closing days of the campaign, it was ultimately a deciding factor in the election.[6] Chicago was particularly hard-hit at the time by the Great Depression.[6] While she did not originally treat it as the central issue of the campaign, by the end, McCormick admitted that, in the election, rather than prohibition, voters were more focused on the economy, saying, "the question is not whether everybody gets a bottle of beer, but whether everybody gets a job".[6] She argued that Democratic rule would worsen the economic turmoil.[6]

Results

J. Hamilton Lewis won by a broad margin, becoming the first Democrat to be popularly elected to the United States Senate from Illinois.[6] McCormick was the first Republican to lose a popular U.S. senate election in Illinois.[6]

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | J. Hamilton Lewis | 1,432,216 | 64.02 | |

| Republican | Ruth Hanna McCormick | 687,469 | 30.73 | |

| Independent Republican | Lottie Holman O'Neill | 99,485 | 4.45 | |

| Socialist | George Koop | 11,192 | 0.50 | |

| Communist | Freeman Thompson | 3,118 | 0.14 | |

| Peace and Prosperity | Louis Warner | 1,078 | 0.05 | |

| American National | Ernest Stout | 1,060 | 0.05 | |

| Anti-League World Court, Anti-Foreign Entanglements | C. Emmet Smith | 763 | 0.03 | |

| Liberty | James J. McGrath | 723 | 0.03 | |

| Majority | 744,747 | 33.29 | ||

| Turnout | 2,237,104 | |||

| Democratic gain from Republican | ||||

Two years later, in the 1932 United States Senate election in Arkansas, Hattie Wyatt Caraway would become the first woman to be elected to the U.S. Senate.[9]

Illinois’ post-economic crash turn to the Democratic Party (Demonstrated by the 1930 Senate race) continued in 1932, with a Democratic sweep of all statewide races (including races for president, U.S. Senate, at-large U.S. House seats, governor, and lieutenant governor). The 1932 elections also saw Democrats capture several additional U.S. House of Representatives seats in Illinois.[27]

Illinois would have to wait 56 years after 1930 to see another woman nominated for U.S. Senate by a major party, with Judy Koehler being the unsuccessful Republican nominee in the 1986 United States Senate election in Illinois.[28] It took 62 years after McCormick's loss before Illinois actually elected a female United States Senator. In 1992, Democrat Carol Moseley Braun would become the first woman to be elected to the U.S. Senate from Illinois.[9][29] In 2016, Democrat Tammy Duckworth would become the second woman elected to the U.S. Senate from Illinois.[9]

- "OFFICIAL VOTE OF THE STATE OF ILLINOIS CAST AT THE GENERAL ELECTION, NOV. 4, 1930 JUDICIAL ELECTIONS, 1929–1930 PRIMARY ELECTION GENERAL PRIMARY, APRIL 8, 1930" (PDF). Illinois State Board of Elections. Retrieved December 15, 2020.[permanent dead link]

- Rhoads, Mark (October 30, 2006). "Illinois Hall of Fame: Ruth Hanna McCormick". Illinois Review. Retrieved January 4, 2019.

- "Senator McCormick Found Dead in Bed in Hotel Apartment Here". Evening Star. February 25, 1925. p. 2. ISSN 2331-9968. Retrieved January 4, 2019.

- "National Affairs: Medill McCormick". Time magazine. March 9, 1925. Archived from the original on November 22, 2011. Retrieved January 9, 2011.

- Hill, Ray (December 16, 2012). "The Senate's Dandy: James Hamilton Lewis of Illinois – The Knoxville Focus". The Knoxville Focus. Retrieved December 16, 2020.

- "Official Vote of the State of Illinois Cast at the General Election, Nov. 6, 1928 Judicial Elections, 1927–1928 Primary Election General Primary, April 10, 1928" (PDF). Illinois State Board of Elections. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 1, 2022. Retrieved December 16, 2020.

- "U.S. Senate: Women Senators". www.senate.gov. United States Senate. Retrieved December 20, 2020.

- "Our Campaigns – Candidate – James O. Monroe". www.ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved December 20, 2020.

- "J. HAMILTON LEWIS SEEKS SENATORSHIP; Announces Demacratic Candidacy in Illinois—ServedTerm in 1913–19.TAKES DIRECT WET STANDHis "Platform" Also Blames theRepublican Party There for Chicago's Financial Plight. (Published 1930)". The New York Times. February 10, 1930. Retrieved December 16, 2020.

- "OFFICIAL VOTE OF THE STATE OF ILLINOIS CAST AT THE GENERAL ELECTION, NOV. 4, 1924 JUDICIAL ELECTIONS, 1923–1924 JUDICIAL ELECTIONS, 1923–1924 SPECIAL ELECTIONS, 1923–1924 PRIMARY ELECTIONS GENERAL PRIMARY, APRIL 8, 1924 PRESIDENTIAL PREFERENCE, APRIL 8, 1924" (PDF). Illinois State Board of Elections. Retrieved December 19, 2020.[permanent dead link]

- "Our Campaigns – Candidate – Newton Jenkins". www.ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved December 16, 2020.

- "NEWTON JENKINS, 55, LAWYER AND SOLDIER; Defeated for Mayor of Chicago and United States Senator". The New York Times. October 17, 1942. Retrieved December 16, 2020 – via timesmachine.nytimes.com.

- Associated Press (September 23, 1929). "Ruth Hanna McCormick Enters Race for United States Senate". Evening Star. p. 21. ISSN 2331-9968. Retrieved January 2, 2019.

- Hard, William (October 27, 1929). "Mrs. McCormick's Senatorial Campaign Reveals Lack of Interest in the Tariff". Evening Star. p. 2. ISSN 2331-9968. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- Lincoln, G. Gould (October 30, 1929). "Politics at Large". Evening Star. p. 8. ISSN 2331-9968. Retrieved January 6, 2019.

- Pickard, Edward W. (April 18, 1930). "Illinois Republicans Name Ruth Hanna McCormick for U.S. Senator". Maryland Independent. p. 3. Retrieved January 6, 2019.

- "Mrs. M'Cormick Routs Deneen in Illinois Primary". Evening Star. April 9, 1930. ISSN 2331-9968. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- Pickard, Edward W. (May 9, 1930). "Farm Board and Chamber of Commerce of U.S. in Open Warfare". Maryland Independent. p. 3. Retrieved January 5, 2019.

- "Our Campaigns – Candidate – George Koop". www.ourcampaigns.com. Retrieved December 17, 2020.

- "Illinois Prohibition Act Repeal Question (1930)". Ballotpedia. Retrieved December 17, 2020.

- Gunderson, Erica (August 25, 2017). "Historical Happy Hour: A Toast to Ruth Hanna McCormick". WTTW News. Retrieved January 4, 2022.

- "Thompson v. McCormicks". Time. Time, Inc. November 3, 1930. Archived from the original on June 5, 2008. Retrieved May 2, 2008.

- "Statistics of the Congressional Election of November 4, 1930" (PDF). Clerk of the United States House of Representatives. Retrieved July 2, 2014.

- "OFFICIAL VOTE OF THE STATE OF ILLINOIS CAST AT THE GENERAL ELECTION, Nov. 8, 1932 JUDICIAL ELECTIONS, 1931-1932 PRIMARY ELECTIONS GENERAL PRIAMRY, PARIL 12, 1932 PRESIDENTIAL PREFERENCE, APRIL 12, 1932" (PDF). Office of the Illinois Secretary of State. Retrieved January 4, 2022.[permanent dead link]

- Neal, Steve (September 14, 1986). "CAN ROLLING PIN BEAT AL THE PAL FOR SENATE SEAT?". chicagotribune.com. Chicago Tribune. Retrieved December 20, 2020.

- "U.S. Senate: Carol Moseley Braun: A Featured Biography". www.senate.gov. United States Senate. Retrieved December 20, 2020.