Action_of_the_Cockcroft,_19_August_1917

Action of the Cockcroft

Military action in WW1

The action of the Cockcroft took place on 19 August 1917, during the Third Battle of Ypres on the Western Front in the First World War. At the Battle of Langemarck (16–18 August 1917) the infantry of the 48th (South Midland) Division (Major-General Robert Fanshawe) and the 11th (Northern) Division (Major General Henry Davies) of XVIII Corps had been stopped well short of their objectives. The British had been shot down by the German garrisons of blockhouses and pillbox outposts of the Wilhelmstellung (the third German defensive position). At a conference called by General Hubert Gough, the Fifth Army commander, on 17 August, Gough and the corps commanders arranged for local attacks to be made at various points, to reach a good jumping-off line for another general attack on 25 August.

| Action of the Cockcroft, 19 August 1917 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Third Battle of Ypres of the First World War | |||||||

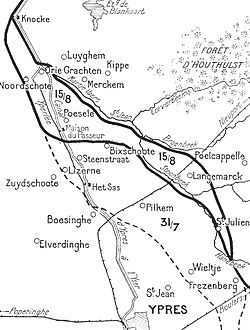

Front line after Battle of Langemarck, 16–18 August 1917 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Sir Douglas Haig Hubert Gough |

Crown Prince Rupprecht Sixt von Armin | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

1/8th Battalion Royal Warwick G Battalion, 1st Tank Brigade | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1 infantry battalion, 11 tanks | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

infantry: 15 wounded tank crews: 2 killed, 13–14 wounded | c. 100 and 30 POW | ||||||

St Julien (Saint-Julien/Sint-Juliaan), a hamlet in the municipality of Langemark-Poelkapelle in West Flanders | |||||||

The commanders of XIX Corps and XVIII Corps were ordered to arrange advances to within about 200 yd (180 m) of the Wilhelmstellung, to come into line with the XIV Corps on the left flank; II Corps, further south, was to capture Inverness Copse on 22 August. At 4:45 a.m. on 19 August, five tanks of the 1st Tank Brigade broke down or ditched; seven others advanced up the St Julian–Poelcappelle road behind a smoke barrage, their noise smothered by low-flying British aircraft. The tanks were followed by parties of the 1/8th Battalion, Royal Warwickshire Regiment, ready to occupy the strong points and pillboxes as their garrisons were overcome by the tanks.

At most of the pillboxes, the German occupants retreated as soon as they saw the tanks; at Triangle Farm, Maison du Hibou and the Cockcroft, the garrisons stood their ground, suffering about 100 casualties and thirty men taken prisoner. Two of the tanks were knocked out and two crew were killed along with 13 to 14 wounded; fifteen Royal Warwicks were also wounded. In 1996, Prior and Wilson wrote that the method was hard to repeat and created unrealistic expectations of the tanks. In 2017, Nick Lloyd wrote that the attack had been "a remarkable exercise in ingenuity and imagination" which raised Tank Corps morale.

German defensive tactics

In July 1917, the system of defence in depth of the German 4th Army (General der Infanterie Sixt von Armin) began with a front system of three breastworks Ia, Ib and Ic, about 200 yd (180 m) apart, garrisoned by the four companies of each front battalion, with listening-posts in no-man's-land. About 2,000 yd (1,800 m) behind was the Albrechtstellung (the second or artillery protective line), the rear boundary of the forward battle zone (Kampffeld). About 25 per cent of the battalions in support were divided into Sicherheitsbesatzungen (security crews) to hold strong-points, the remainder being Stoßtruppen (storm troops) to counter-attack towards them from the back of the Kampffeld.[1] Dispersed in front of the line were divisional Scharfschützen (machine-gun armed marksmen) in the Stützpunktlinie (strongpoint line) a line of machine-gun nests prepared for all-round defence. The Albrechtstellung also marked the front of the main battle zone (Grosskampffeld) which was about 2,000 yd (1,800 m) deep, containing most of the field artillery of the Stellungsdivisionen (ground holding divisions), behind which was the Wilhelmstellung. In the pillboxes of the Wilhelmstellung were reserve battalions of the front-line regiments, held back as divisional reserves, ready to counter-attack.[2]

Battle of Langemarck

At the Battle of Langemarck, (16–18 August), XVIII Corps (Lieutenant-General Ivor Maxse) had attacked at 4:45 a.m. with the 145th Brigade of the 48th (South Midland) Division and 34th Brigade of the 11th (Northern) Division, supported by eight tanks. The tanks were ordered to keep off the roads, but the approach to the front line was so boggy that the tanks were cancelled and sent back. The 145th Brigade eventually captured the last house at the north end of St Julien, taking forty prisoners and a machine-gun. The advance resumed; as the first wave went over a rise 200 yd (180 m) east of the Steenbeek, it was caught in crossfire from Hillock Farm and Maison du Hibou 200 yd (180 m) beyond. Border House and the gun pits, either side of the north-east bearing St. Julien–Winnipeg road, were captured; attempts to press on were costly failures. Parties that reached Springfield Farm disappeared and the 145th Brigade suffered 911 casualties.[3]

The 145th Brigade consolidated on a line from the village to the gun pits, Jew Hill and Border House. At 9:00 a.m., German troops massed around Triangle Farm and made an abortive counter-attack at 10:00 a.m.[4] Another counter-attack after dark was repulsed at the gun pits and at 9:30 p.m., a counter-attack from Triangle Farm was defeated. The Germans in Maison du Hibou and Triangle Farm, opposite the 48th (South Midland) Division, caught the right of the 34th Brigade, 11th (Northern) Division in enfilade as it was being fired on from pillboxes to its front. The 34th Brigade captured Haanixbeer Farm and the cemetery nearby but lost the barrage and was unable to capture the Cockcroft and Bülow Farm. On the right, the troops dug in facing Maison du Hibou and Triangle Farm to the east and on the left, the brigade dug in 100 yd (91 m) north-east of Langemarck, opposite the White House and Pheasant Farm, having suffered 781 casualties.[4] German artillery-fire, directed by observers on higher ground to the east, inflicted many casualties on the British troops holding the new line beyond Langemarck.[5]

Fifth Army

Major-General Oliver Nugent (36th [Ulster] Division), reported that German artillery could not bombard advancing British troops in the German forward zone, in which the German defensive positions were lightly held and distributed in depth. The advance of British troops following up had been much easier to obstruct; helping the foremost infantry was more important than counter-battery fire, even if it had failed to suppress the German guns. Nugent wanted fewer field guns in the creeping barrage and the surplus used to fire sweeping (side-to-side) barrages. Shrapnel shells should be fuzed to burst higher up, to hit the insides of shell holes; creeping barrages should be slower, with more and longer pauses, during which the barrages from field artillery and 60-pounder guns should sweep from side to side and search (move back-and-forth).[6]

The infantry should change formation from skirmish lines to mobile company columns, equipped with a machine-gun and Stokes mortar, advancing on a narrow front, since skirmish lines were impractical in muddy crater fields and broke up under machine-gun fire.[6] Tanks to help capture pillboxes had bogged down behind the British front-line and air support had been restricted by the weather, particularly by low cloud early on and a lack of aircraft. One aircraft per corps had been reserved for counter-attack patrol and two aircraft per division for ground attack; only eight aircraft had been available to cover the Fifth Army front and engage German counter-attacks.[7] Signalling had failed at vital moments and deprived the infantry of artillery support, making German counter-attacks much more effective where the Germans had artillery observation. The 56th (London) Division report recommended that the depth of the advance be shortened to give more time for consolidation and to minimise the organisational and communication difficulties being caused by the muddy ground and wet weather.[8] Artillery commanders asked for two aircraft per division exclusively to conduct counter-attack patrols.[9]

British preparations

| Date | Rain mm |

°F | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16 | 0.0 | 68 | dull |

| 17 | 0.0 | 72 | fine |

| 18 | 0.0 | 74 | fine |

| 19 | 0.0 | 69 | dull |

| 20 | 0.0 | 71 | dull |

During the Battle of Langemarck, German machine-gunners in the blockhouses and pillbox outposts of the Wilhelmstellung on the XVIII Corps front (Hillock Farm, Maison du Hibou, Triangle Farm and the Cockcroft to the British) had shot down the infantry of the 48th (South Midland) Division and 11th (Northern) Division well short of their objectives. At a conference with the Fifth Army corps commanders on 17 August, Gough complained that troops had failed to hold captured ground and considered court-martialling some NCOs and officers. Gough also thought that divisions had been relieved too frequently, which had exhausted fresh divisions before the attack.[12] The corps commanders were asked to propose attacks to reach the final objectives, where their divisions had fallen short on 16 August. Lieutenant-General Claud Jacob (II Corps) wanted to attack the brown line and then the yellow line, Lieutenant-General Herbert Watts (XIX Corps) wanted to attack the purple line; Maxse (XVIII Corps) preferred to attack the dotted purple line, preparatory to attacking the yellow line along with XIX Corps.[13]

The proposed attacks on the plethora of "lines" marked on staff maps were intended to reach good jumping off points for an attack by II, XIX and XVIII corps on 25 August. Attacking in different places and at different times, risked defeat in detail; if the artillery failed sufficiently to suppress German machine-gunners when the infantry were struggling through mud and waterlogged shell-holes, the tactics used by the infantry would be irrelevant.[13] During the conference, patrols of the 48th (South Midland) Division advanced towards Springfield Farm and Hillock Farm to look for posts containing parties from the attack on 16 August. A line of outposts were discovered south of Maison du Hibou and a German post was found 40 yd (37 m) west of Hillock Farm; no British posts were found near Springfield. The reconnaissance clarified the position of the front line, which made it possible to bring a bombardment for the next attack closer to the British posts.[14]

XVIII Corps plan

After the Battle of Langemarck, the British outpost line in the XVIII Corps area ran east and north of St Julien; about 1,000 yd (910 m) beyond, the north bearing St Julien–Poelcapelle road and the Zonnebeke–Langemarck road, running north-west, crossed. The roads formed a triangle with a road eastwards out of St Julien, which cut the Zonnebeke–Langemarck road at the Winnipeg strong point. There was another east–west road 250 yd (230 m) from the point of the triangle. The objectives were inside the triangle except for Maison du Hibou to the west, 300 yd (270 m) along the fourth road and the Cockcroft, 450 yd (410 m) further north, up the Zonnebeke–Langemarck road.[15] British artillery had made many attempts to destroy the German fortifications; field-gun shells were ineffective and heavy artillery was inaccurate.[16]

A dry spell had begun on 16 August and some of the fortifications were near roads, which the Germans had kept in good condition, making it possible for tanks to drive on them and engage the strong points.[17] Maison du Hibou, a fortified farm building, had an eighty-man garrison and the Cockcroft, another fortified farm, even more; Triangle and Hillock farms were somewhat smaller. Maxse was told by the 48th (South Midland) Division brigadier-generals (Gerald Sladen, Herbert Done and Donald Watt) to expect 600–1,000 casualties in an attack on the strong points. In June, the 1st Tank Brigade (Colonel Christopher Baker-Carr) had been allotted to XVIII Corps, the 3rd Tank Brigade to XIX Corps and the 2nd Tank Brigade to II Corps.[18] Maxse consulted Baker-Carr, who claimed that a tank attack could take the farms and blockhouses for half the cost in casualties, provided that there was a smoke barrage instead of artillery-fire.[19] At meetings on 17 and 18 August, the tank and infantry commanders agreed that the tanks, seven of which had already been moved into St Julien and camouflaged, would drive forward under a smoke barrage and silence the German machine-gunners in the blockhouses and pillboxes.[20]

Baker-Carr formed a composite company from G Battalion, 1st Tank Brigade and held rehearsals in which the tanks attacked the fortifications from the rear, where they were most vulnerable and the lines of retreat of their garrisons could be blocked.[19] The infantry was to follow in platoons 250 yd (230 m) behind each tank, waiting for a signal (a shovel waved out of the manhole in the roof) as the signal to move up to the strong point.[21] The gun pits, Hillock Farm, Vancouver, Triangle Farm, Maison du Hibou and the Cockcroft were to be attacked by one tank each; two more tanks were to attack Winnipeg Cemetery and Springfield; a floater and four tanks in reserve at California Trench were to be ready for contingencies.[22][lower-alpha 2] Once the tank crews sent the signal, a company of the 1/8th Worcestershire Regiment (1/8th Worcester) from the 144th Brigade would rush forward and occupy Maison du Hibou and Triangle Farm, as a company of the Birmingham Rifles (1/5th Battalion, Royal Warwickshire Regiment [1/5th Warwick]), 143rd Brigade, was to capture Hillock Farm.[23] The smoke barrage was due to begin at 4:45 a.m. on 19 August as the tanks drove out of St Julien up the St Julien–Poelcappelle road; aircraft were to fly low overhead to drown the sound of the tanks.[24]

German defences

On 31 July, the German front line north of the Ypres–Roulers railway and the Kampffeld had been overrun and the garrisons lost. The new front line was between the Albrechtstellung and the Wilhelmstellung, behind which was the rearward battle zone (rückwärtiges Kampffeld). The main defensive engagement had been fought in the Grosskampffeld by the reserve regiments and Eingreif divisions of the 4th Army, against depleted, tired and disorientated attackers, whose advance had been slowed by the forward garrisons. The new German front was a line of shell holes backed by the fortified farms, strong points and pillboxes of the Grosskampffeld in front of the Wilhelmstellung.[25] On 16 August, the British had tried to capture the Wilhemstellung; in the XVIII Corps area, the British artillery had destroyed few of the pillboxes and fortified farms in the Grosskampffeld or overcome the German artillery, which inflicted 81 per cent of the wounds suffered by the infantry of the 11th (Northern) Division. The division had captured most of its objectives, but the 48th (South Midland) Division on the right barely advanced 100 yd (91 m).[26] After 16 August, the Germans increased the size of regimental sectors to make more room to disperse and divided the field artillery, one part to be kept hidden and used only during big attacks.[27]

Only seven tanks of the composite company, one male tank and six female tanks, were operational when the attack began at 4:45 a.m. the others having already broken down or bogged.[28][lower-alpha 3] The tanks drove out of St Julien, one at a time towards Hillock Farm, about 550 yd (500 m) up the road, which took until 6:00 a.m.; the farm was found to be empty and was occupied by the 1/8th Warwick. Tank G. 29 (Second-Lieutenant A. G. Barker) reached the road junction at Triangle Farm but could not turn left down the road for Maison du Hibou, as the road had been obliterated. G. 29 was driven another 125 yd (114 m) along the Poelcappelle road, which brought the tank to the rear of the strong point. The crew tried to drive cross-country and at 250 yd (230 m), opened fire with the 6-pounder in the left sponson. After firing forty times, about sixty Germans fled from Maison du Hibou, half being shot down and the remainder taken prisoner by the 1/8th Warwick. From the road, the crew of tank G. 31 engaged the blockhouse with its Lewis guns but then returned to the rally-point with engine trouble.[22]

G. 29 bogged but was able to engage the Germans in the Wilhemstellung with the gun in the right sponson, until the tank sank too far into the mud to bring the gun to bear. At about 11:15 a.m., the crew disabled the 6-pounders, dismounted the Lewis guns and handed them to the 1/8th Warwick.[22] The Germans in Triangle Farm held their ground until the 1/8th Warwick, covered by a tank (possibly G. 31), got inside and fought the garrison hand-to-hand. Tank G. 34 (Second-Lieutenant Coutts) headed for the Cockcroft, the most distant objective, 2,400 yd (1.4 mi; 2.2 km) from St Julien, up the Zonnebeke–Langemarck road and it took until 6:45 a.m. to reach the fortification. The crew and the garrison exchanging machine-gun fire for about 15 minutes, until about fifty Germans emerged from the Cockcroft and dugouts nearby, only to be shot down by machine-gun fire from the tank.[29]

G. 34 ditched south of the Cockcroft soon after and the crew set up their Lewis guns in shell-holes nearby. As the 1/8th Warwick were nowhere to be seen, Coutts sent a messenger pigeon back with the news and two of the crew to find the troops. The 1/8th Warwick refused to advance until Coutts came back and found an officer to order sixty men forward and dig in along the Lewis gun cordon. The crew remained until 5:25 p.m. then retired after putting a guard of three rifle-bombers in the tank and camouflaging it. At the other fortified farms and strong points, merely the arrival of tanks induced the garrisons to run and the British were able to establish their own line of outposts up the west side of the St Julien–Poelcappelle road; five of the seven tanks engaged surviving to reach the rally-point. The 1/8th Warwick suffered only 15 wounded and the tank crews two men killed and eleven wounded, inflicting about 100 casualties on the Germans and taking 30 prisoners.[29][lower-alpha 4]

Analysis

After the action, Lieutenant-Colonel J. F. C. Fuller wrote a memorandum Minor Tank and Infantry Operations against Strong Points (23 August 1917). Fuller described conventional minor tactics, combined with the methods used by the Tank Corps, that had succeeded during the battles around Ypres and which became influential in the adoption of the Single File Drill.[31] In 1919, Williams-Ellis and Williams-Ellis wrote that the action was memorable and that a German officer had been found hanged by his men in one of the strongpoints and in 1931, Hubert Gough called the attack a "very successful little operation...".[32] In 1995, J. P. Harris called the attack on the pillboxes "One brilliant little feat of arms....", which justified the decision made by Haig, to keep some tanks in Flanders, even after the heavy rains began in August.[33]

In 1996, Prior and Wilson wrote that in just over two hours Maxe's "novel stratagem" had captured five formidable fortified posts, yet the method was not feasible in most of the salient. On 22 August, XVIII Corps attacked with tanks again; the objectives were too far from the roads and the tanks ditched when the crews tried to drive closer.[34] In 2008, J. P. Harris described the operation as "brilliant" and of "amazingly low cost".[35] In 2014, Robert Perry wrote that the operation was spectacularly successful but that it created unrealistic expectations of what the tanks could do.[29] In 2017, Nick Lloyd wrote that the action had been "a remarkable exercise in ingenuity and imagination" and that the success raised the morale of the Tank Corps.[36]

Casualties

In 1919, Williams-Ellis recorded fifteen wounded and two killed among the infantry; fourteen wounded among the tank crews.[37] In the official history volume (1948), James Edmonds, the official historian, recorded slight infantry casualties with three killed and two of the seven tanks in the attack lost.[38] In 1996, Prior and Wilson wrote that the British had fifteen infantry and thirteen Tank Corps casualties.[17]

Subsequent operations

On 20 August, a special gas and smoke bombardment took place on Jehu Trench, beyond Lower Star Post on the front of the 24th Division (II Corps). The 61st (2nd South Midland) Division (XIX Corps) took a German outpost near Somme Farm and on 21 August, the 38th (Welsh) Division (XIV Corps), pushed forward its left flank.[39] At 4:45 a.m. on 22 August, XIX Corps and XVIII Corps attacked again to close up to the Wilhemstellung, ready for the general attack due on 25 August. The three-brigade attack on the XIX Corps front by the fresh 15th (Scottish) Division and the 61st (2nd South Midland) Division, was a costly failure. Four tanks to support the 45th Brigade on the right flank of the 15th (Scottish) Division ditched short of the front line on the Frezenberg–Zonnebeke road and four of the six survivors, starting west of the Pommern Redoubt, ditched in the front line. The 15th Division advance was soon stopped by fire from the Potsdam, Vampir, Borry Farm and Iberian Farm blockhouses; infantry who pressed on closer to the objective disappeared.[40]

On the left flank, troops of the 44th Brigade managed to advance some way up the slope of Hill 35, assisted by two tanks, until stopped short by machine-gun fire from Gallipoli Farm. The 184th Brigade of the 61st (2nd South Midland) Division managed to advance about 600 yd (550 m) and captured Pond Farm, Somme Farm and Hindu Cottage. On the XVIII Corps front, the 48th (South Midland) Division and the 11th (Northern) Division were to have advanced in a thin skirmish line preceded by tanks. Ten tanks were allotted to the 48th (South Midland) Division. Behind the British front line, on the St Julien–Poelcappelle road, six of the tanks bogged down or were hit by shells and knocked out. The remaining four tanks assisted the 143rd Brigade to capture Keerselare, Vancouver Farm and Springfield Farm, the latter being re-taken soon after; two tanks helped troops of the 33rd Brigade, 11th (Northern) Division capture Bülow Farm.[40]

- Rainfall measured at Vlamertinghe, temperature at Ypres.[11]

- The account by Robert Perry (2014) is derived from the War Diary of the 1st Brigade (WO95/98), held at the National Archives and has been given precedence in this article over accounts by earlier authors, who did not have access to official records.[28]

- In Tanks in the Great War, 1914–1918 by J. F. C. Fuller (1920) eleven tanks reached St Julien at 4:45 a.m., three ditched and eight emerged on the St Julien–Poelcappelle road. Hillock Farm was captured at 6:00 a.m. and fifteen minutes later Maison du Hibou fell when a tank got within 80 yd (73 m) and fired fifty shells, forcing the garrison of twenty men to run out. Half were killed by machine-gun fire from a female tank and the rest captured. Triangle Farm was overrun soon afterwards, when tanks drove the garrisons under cover, where they were unable to engage the infantry, which were following close behind the tanks. A female tank ditched 50 yd (46 m) from the Cockcroft at 6:45 a.m. and about a hundred German soldiers ran out of the buildings and dug outs nearby, most being killed or captured. The tank crews had 14 casualties and the infantry 15, instead of the expected 600.[30]

- Wynne 1976, p. 292.

- Wynne 1976, p. 288.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 199; McCarthy 1995, p. 53.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 199.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 199; McCarthy 1995.

- Falls 1996, pp. 122–124.

- Dudley Ward 2001, pp. 160–161.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 201.

- Perry 2014, pp. 203, 230.

- Perry 2014, p. 203.

- Prior & Wilson 1996, p. 105.

- Simpson 2006, p. 101.

- Mitchinson 2017, p. 170.

- Browne 1920, pp. 197–198.

- Perry 2014, p. 225; Williams-Ellis & Williams-Ellis 1919, p. 148.

- Prior & Wilson 1996, p. 106.

- Fuller 1920, p. 117.

- Mitchinson 2017, p. 171.

- Browne 1920, p. 197.

- Perry 2014, p. 225.

- Mitchinson 2017, p. 171; Perry 2014, p. 225.

- Williams-Ellis & Williams-Ellis 1919, p. 149; Perry 2014, p. 225.

- Wynne 1976, pp. 289, 303.

- Prior & Wilson 1996, p. 102.

- Wynne 1976, p. 303.

- Perry 2014, pp. 224–226.

- Perry 2014, pp. 226–227.

- Fuller 1920, pp. 122–123.

- Hammond 2005, p. 168.

- Williams-Ellis & Williams-Ellis 1919, pp. 149, 151; Gough 1968, pp. 205–206.

- Harris 1995, p. 106.

- Prior & Wilson 1996, pp. 106–107.

- Harris 2008, p. 370.

- Lloyd 2017, pp. 143–144.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 202.

- McCarthy 1995, pp. 55–58.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 202–203.

Books

- Browne, D. G. (1920). The Tank in Action (online scan ed.). Edinburgh: W. Blackwood. OCLC 699081445. Retrieved 24 July 2017 – via Archive Foundation.

- Dudley Ward, C. H. (2001) [1921]. The Fifty Sixth Division 1914–1918 (1st London Territorial Division) (facs. Naval and Military Press ed.). London: Murray. ISBN 978-1-84342-111-5.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1991) [1948]. Military Operations France and Belgium, 1917: 7 June – 10 November. Messines and Third Ypres (Passchendaele). History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. Vol. II (facs. Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). Nashville, TN: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-89839-166-4.

- Falls, C. (1996) [1922]. The History of the 36th (Ulster) Division (Constable ed.). Belfast: McCaw, Stevenson & Orr. ISBN 978-0-09-476630-3. Retrieved 24 July 2017 – via Project Gutenburg.

- Fuller, J. F. C. (1920). Tanks in the Great War, 1914–1918 (online scan ed.). New York: E. P. Dutton. OCLC 559096645. Retrieved 24 July 2017 – via Archive Foundation.

- Gough, H. de la P. (1968) [1931]. The Fifth Army (repr. Cedric Chivers ed.). London: Hodder & Stoughton. OCLC 59766599.

- Harris, J. P. (1995). Men, Ideas and Tanks: British Military Thought and Armoured Forces, 1903–39. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-4814-2.

- Harris, J. P. (2008). Douglas Haig and the First World War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89802-7.

- Lloyd, N. (2017). Passchendaele: A New History. London: Viking. ISBN 978-0-241-00436-4.

- McCarthy, C. (1995). The Third Ypres: Passchendaele, the Day-By-Day Account. London: Arms & Armour Press. ISBN 978-1-85409-217-5.

- Mitchinson, K. W. (2017). The 48th (South Midland) Division 1908–1919 (hbk. ed.). Solihull: Helion. ISBN 978-1-911512-54-7.

- Perry, R. A. (2014). To Play a Giant's Part: The Role of the British Army at Passchendaele. Uckfield: Naval & Military Press. ISBN 978-1-78331-146-0.

- Prior, R.; Wilson, T. (1996). Passchendaele: the Untold Story (online scan ed.). London: Yale. ISBN 978-0-300-07227-3 – via Archive Foundation.

- Simpson, A. (2006). Directing Operations: British Corps Command on the Western Front 1914–18. Stroud: Spellmount. ISBN 978-1-86227-292-7.

- Williams-Ellis, A.; Williams-Ellis, C. (1919). The Tank Corps (online scan ed.). New York: G. H. Doran. OCLC 317257337. Retrieved 29 March 2014 – via Archive Foundation.

- Wise, S. F. (1981). Canadian Airmen and the First World War. The Official History of the Royal Canadian Air Force. Vol. I. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-2379-7.

- Wynne, G. C. (1976) [1939]. If Germany Attacks: The Battle in Depth in the West (Greenwood Press, Westport, CT ed.). Cambridge: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-8371-5029-1.

Theses

- Hammond, C. B. (2005). The Theory and Practice of Tank Co-operation with other Arms on the Western Front during the First World War (PhD). University of Birmingham. OCLC 911156915. EThOS uk.bl.ethos.433696. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

Books

- Foerster, Wolfgang, ed. (1939). Der Weltkrieg 1914 bis 1918: Die Militärischen Operationen zu Lande Zwölfter Band, Die Kriegführung im Frühjahr 1917 [The World War 1914 to 1918, Military Land Operations Twelfth Volume, Warfare in the Spring of 1917] (in German). Vol. XII (online scan ed.). Berlin: Verlag Ernst Siegfried Mittler und Sohn. OCLC 248903245. Retrieved 29 June 2021 – via Die digitale landesbibliotek Oberösterreich.

- Histories of Two Hundred and Fifty-one Divisions of the German Army which Participated in the War (1914–1918). Document (United States. War Department) number 905. Washington D.C.: United States Army, American Expeditionary Forces, Intelligence Section. 1920. OCLC 565067054. Retrieved 24 July 2017.

- Liddle, P. H., ed. (1997). Passchendaele in Perspective: The Third Battle of Ypres. Barnsley: Pen & Sword. ISBN 978-0-85052-588-5.

- Rawson, A. (2017). The Passchendaele Campaign 1917 (1st ed.). Barnsley: Pen & Sword. ISBN 978-1-52670-400-9.

Theses

- Simpson, Andrew (2001). The Operational Role of British Corps Command on the Western Front 1914–18. discovery.ucl.ac.uk (PhD thesis). London: London University. OCLC 53564367. EThOS uk.bl.ethos.367588. Retrieved 13 March 2017.