Empty_tomb

Empty tomb

Christian tradition about the tomb of Jesus

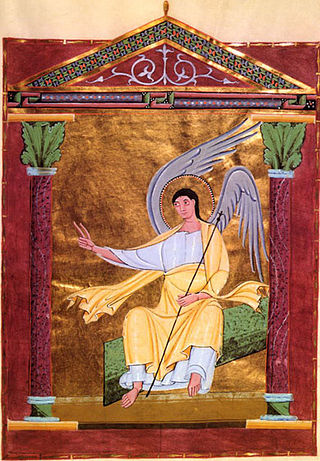

The empty tomb is the Christian tradition that the tomb of Jesus was found empty after his crucifixion.[1] The canonical gospels each describe the visit of women to Jesus' tomb. Although Jesus' body had been laid out in the tomb after crucifixion and death, the tomb is found to be empty, the body gone, and the women are told by angels (or a "young man [...] dressed in a white robe") that he has risen.

Overview

Although the four canonical gospels detail the narrative, oral traditions existed well before the composition of the gospels on the matter.[2] The four gospels were almost certainly not by eyewitnesses, at least in their final forms, but were instead the end-products of long oral and written transmission.[3] Three of the four (Mark, Luke, and Matthew) are called the synoptics (meaning "seeing together"), because they present very similar stories, and it is generally agreed that this is because two of them, Matthew and Luke, have used Mark as their source.[4][5] The earliest of them, Mark, dates probably from around AD 65–70, some forty years after the death of Jesus,[6] while Matthew and Luke date from around AD 85–90.[7] John, the last gospel to be completed, began circulating between 90 and 110,[8] and its narrative of the empty tomb is not merely a different form of the story told in the synoptics, but after John 20:2 differs to such an extent that it cannot be harmonised with the earlier three.[9][10]

In the original ending of the Gospel of Mark, the oldest, three women visit the tomb to anoint the body of Jesus, but find instead a "young man [...] dressed in a white robe" who tells them that Jesus will meet the disciples in Galilee.[11] The women then flee, telling no one. Matthew introduces guards and a doublet where the women are told twice, by angels and then by Jesus, that he will meet the disciples in Galilee.[12] Luke changes Mark's one "young man [...] dressed in a white robe" to two, adds Peter's inspection of the tomb,[13] and deletes the promise that Jesus would meet his disciples in Galilee.[14] John reduces the women to the solitary Mary Magdalene, and introduces the "beloved disciple" who visits the empty tomb with Peter and is the first to understand its significance.[15][16]

The synoptics

Mark 16:1–8 probably represents a complete unit of oral tradition taken over by the author.[17] It concludes with the women fleeing from the empty tomb and telling no one what they have seen, and the general scholarly view is that this was the original ending of this gospel, with the remaining verses, Mark 16:9–16, being added later.[18][11] The imagery of a young man in a white robe, and the reaction of the women, indicates that this is an encounter with an angel.[19] The empty tomb fills the women with fear and alarm, not with faith in the risen Lord,[20] although the mention of a meeting in Galilee is evidence of some sort of previous, pre-Markan, tradition linking Galilee and the resurrection.[21]

Matthew revises Mark's account to make it more convincing and coherent.[12] The description of the angel is taken from Daniel's angel with a face "like the appearance of lightning" (Daniel 10:6) and his God with "raiment white as snow" (Daniel 7:9), and Daniel also provides the reaction of the guards (Daniel 10:7–9).[22] The introduction of the guard is apparently aimed at countering stories that Jesus' body had been stolen by his disciples, thus eliminating any explanation of the empty tomb other than that offered by the angel, that he has been raised.[12] Matthew introduces a doublet whereby the women are told twice, by the angels and then by Jesus, that he will meet the disciples in Galilee (Matthew 28:7–10)—the reasons for this are unknown.[12]

Luke changes Mark's one "young man [...] dressed in a white robe" to two, makes reference to earlier passion predictions (Luke 24:7), and adds Peter's inspection of the tomb.[13] He also deletes the promise that Jesus would meet his disciples in Galilee.[14] In Mark and Matthew, Jesus tells the disciples to meet him there, but in Luke the post-resurrection appearances are only in Jerusalem.[23] Mark and Luke report that the women visited the tomb in order to finish anointing the body of Jesus. While Mark doesn't provide any explanation why they couldn't complete their task on the evening of the crucifixion,[24] Luke explains that the first sundown of sabbath had already begun when Jesus was being buried, and that the women were observant of sabbath regulations.[25] In Matthew the women came simply to see the tomb,[26] and in John no reason is given.[27] John reduces the women to the solitary Mary Magdalene, which is consistent with Mark 16:9. The story ends with Peter visiting the tomb and seeing the burial cloths, but instead of believing in the resurrection he remains perplexed.[28]

The following table, with translations from the New International Version, allows the three versions to be compared.[9] (Luke 24:12, in which Peter goes to the tomb, may be an addition to the original gospel taken from John's version of the narrative).[29]

| Mark 16:1–8 | Matthew 28:1–10 | Luke 24:1–12 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| The women at the tomb | Mark 16:1–4 When the Sabbath was over, Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James, and Salome bought spices so that they might go to anoint Jesus' body. Very early on the first day of the week, just after sunrise, they were on their way to the tomb, and they asked each other, "Who will roll the stone away from the entrance of the tomb?" But when they looked up, they saw that the stone, which was very large, had been rolled away. |

Matthew 28:1–4 After the Sabbath, at dawn on the first day of the week, Mary Magdalene and the other Mary went to look at the tomb. There was a violent earthquake, for an angel of the Lord came down from heaven and, going to the tomb, rolled back the stone and sat on it. |

Luke 24:1–2 On the first day of the week, very early in the morning, the women took the spices they had prepared and went to the tomb. They found the stone rolled away from the tomb, |

| The angelic message | Mark 16:5–7 As they entered the tomb, they saw a young man dressed in a white robe sitting on the right side, and they were alarmed. "Don't be alarmed," he said. "You are looking for Jesus the Nazarene, who was crucified. He has risen! He is not here. See the place where they laid him. But go, tell his disciples and Peter, 'He is going ahead of you into Galilee. There you will see him, just as he told you.'" |

Matthew 28:5–7 His appearance was like lightning, and his clothes were white as snow. The guards were so afraid of him that they shook and became like dead men. The angel said to the women, "Do not be afraid, for I know that you are looking for Jesus, who was crucified. He is not here; he has risen, just as he said. Come and see the place where he lay. Then go quickly and tell his disciples: 'He has risen from the dead and is going ahead of you into Galilee. There you will see him.' Now I have told you." |

Luke 24:3–7 but when they entered, they did not find the body of the Lord Jesus. While they were wondering about this, suddenly two men in clothes that gleamed like lightning stood beside them. In their fright the women bowed down with their faces to the ground, but the men said to them, "Why do you look for the living among the dead? He is not here; he has risen! Remember how he told you, while he was still with you in Galilee: 'The Son of Man must be delivered over to the hands of sinners, be crucified and on the third day be raised again.' " Then they remembered his words. |

| Informing the disciples | Mark 16:8

Trembling and bewildered, the women went out and fled from the tomb. They said nothing to anyone, because they were afraid. |

Matthew 28:8

So the women hurried away from the tomb, afraid yet filled with joy, and ran to tell his disciples. |

Luke 24:9–11

When they came back from the tomb, they told all these things to the Eleven and to all the others. It was Mary Magdalene, Joanna, Mary the mother of James, and the others with them who told this to the apostles. But they did not believe the women, because their words seemed to them like nonsense. |

| The message from Jesus | Matthew 28:9–10

Suddenly Jesus met them. "Greetings," he said. They came to him, clasped his feet and worshiped him. Then Jesus said to them, "Do not be afraid. Go and tell my brothers to go to Galilee; there they will see me." |

||

| Disciples at the tomb | Luke 24:12

Peter, however, got up and ran to the tomb. Bending over, he saw the strips of linen lying by themselves, and he went away, wondering to himself what had happened. |

John

John's chapter 20 can be divided into three scenes: (1) the discovery of the empty tomb, verses 1–10; (2) appearance of Jesus to Mary Magdalene, 11–18; and (3) appearances to the disciples, especially Thomas, verses 19–29; the last is not part of the "empty tomb" episode and is not included in the following table.[30] He introduces the "beloved disciple", who visits the tomb with Peter and understands its significance before Peter.[15] The author seems to have combined three traditions, one involving a visit to the tomb by several women early in the morning (of which the "we" in "we do not know where they have taken him" is a fragmentary remnant), a second involving a visit to the empty tomb by Peter and perhaps by other male disciples, and a third involving an appearance of Jesus to Mary Magdalene.[27] John has reduced this to the solitary Mary Magdalene in order to introduce the conversation between her and Jesus, but the presence of "we" when she informs the disciples may be a remnant of the original group of women,[16] since mourning and the preparation of bodies by anointing were social rather than solitary activities.[16]

| John 20:1–10 Discovery of the empty tomb | John 20:11–18 Appearance of Jesus to Mary Magdalene | |

|---|---|---|

| Mary Magdalene at the tomb | John 20:1 Early on the first day of the week, while it was still dark, Mary Magdalene went to the tomb and saw that the stone had been removed from the entrance. |

John 20:11

Now Mary stood outside the tomb crying. As she wept, she bent over to look into the tomb |

| The angelic message | John 20:12–13

and saw two angels in white, seated where Jesus' body had been, one at the head and the other at the foot. They asked her, "Woman, why are you crying?" "They have taken my Lord away," she said, "and I don't know where they have put him." | |

| Informing the disciples | John 20:2

So she came running to Simon Peter and the other disciple, the one Jesus loved, and said, "They have taken the Lord out of the tomb, and we don't know where they have put him!" |

|

| Disciples at the tomb | John 20:3–10

So Peter and the other disciple started for the tomb. Both were running, but the other disciple outran Peter and reached the tomb first. He bent over and looked in at the strips of linen lying there but did not go in. Then Simon Peter came along behind him and went straight into the tomb. He saw the strips of linen lying there, as well as the cloth that had been wrapped around Jesus' head. The cloth was still lying in its place, separate from the linen. Finally the other disciple, who had reached the tomb first, also went inside. He saw and believed. (They still did not understand from Scripture that Jesus had to rise from the dead.) Then the disciples went back to where they were staying. |

|

| The message from Jesus | John 20:14–18

At this, she turned around and saw Jesus standing there, but she did not realize that it was Jesus. He asked her, "Woman, why are you crying? Who is it you are looking for?" Thinking he was the gardener, she said, "Sir, if you have carried him away, tell me where you have put him, and I will get him." Jesus said to her, "Mary." She turned toward him and cried out in Aramaic, "Rabboni!" (which means "Teacher"). Jesus said, "Do not hold on to me, for I have not yet ascended to the Father. Go instead to my brothers and tell them, 'I am ascending to my Father and your Father, to my God and your God.'" Mary Magdalene went to the disciples with the news: "I have seen the Lord!" And she told them that he had said these things to her. |

Cultural and religious context

Although Jews, Greeks, and Romans all believed in the reality of resurrection, they differed in their respective conceptions and interpretations of it.[31][32][33] Christians certainly knew of numerous resurrection-events allegedly experienced by persons other than Jesus: the early 3rd-century Christian theologian Origen, for example, did not deny the resurrection of the 7th-century BCE semi-legendary Greek poet Aristeas or the immortality of the 2nd-century CE Greek youth Antinous, the beloved of the Roman Emperor Hadrian, but said the first had been the work of demons, not God, while the second, unlike Jesus, was unworthy of worship.[34][35]

Mark Goodacre writes that using "empty tomb" to refer to the disappearance of Jesus' body may be a misnomer since first-century tombs in Judea were built to house multiple bodies. As such, Mark narrates that the women had seen the spot where Jesus was laid while the later gospels state that the tomb was "new" and unused.[36]

"Assumption" or "translation" stories

The composition and classification of the empty tomb story have been the subject of considerable debate.[37][38] Several scholars have argued that the empty tomb story in Mark is similar to "assumption" or "translation" stories, and not a resurrection story, in which certain special individuals are described as being transported into the divine realm (heaven) before or after their death.[39] Adela Yarbro Collins, for example, explains the Markan narrative as a Markan deduction from an early Christian belief in the resurrection. She classifies it as a translation story, meaning a story of the removal of a newly-immortal hero to a non-Earthly realm.[40] According to Daniel Smith, a missing body was far more likely to be interpreted as an instance of removal by a divine agent than as an instance of resurrection or resuscitation.[41] Richard C. Miller compares the ending of Mark to Hellenistic and Roman translation stories of heroes which involve missing bodies.[42]

However, Smith also notes that certain elements within Mark's empty tomb story are inconsistent with an assumption narrative, most importantly the response to the women from the young man at the tomb: ("He is risen" Mark 16:6).[citation needed] Pointing to the existence in earlier Jewish texts both of the idea of resurrection from the grave and of that of a heavenly assumption of the resurrected, Dale Allison argues that resurrection and assumption are not mutually contradicting ideas, and that the empty tomb story probably involved both from the beginning.[43]

Skepticism about the empty tomb narrative

Early on,[when?] the stories about the empty tomb were met with skepticism. The Gospel of Matthew already mentions stories that the body was stolen from the grave.[44] Other suggestions, not supported in mainstream scholarship, are that Jesus had not really died on the cross, or was lost due to natural causes.[45]

The absence of any reference to the story of Jesus' empty tomb in the Pauline epistles and the Easter kerygma (preaching or proclamation) of the earliest church, originating perhaps in the Christian community of Antioch in the 30s and preserved in 1 Corinthians,[46] has led some scholars to suggest that Mark invented it.[according to whom?] Allison, however, finds this argument from silence unconvincing.[47] Other scholars have argued that instead, Paul presupposes the empty tomb, specifically in the early creed passed down in 1 Cor. 15.[48][49]

Most scholars believe that John wrote independently of Mark and that the Gospel of Mark and the Gospel of John contain two independent attestations of an empty tomb, which in turn suggests that both used already-existing sources[50] and appealed to a commonly held tradition, though Mark may have added to and adapted that tradition to fit his narrative.[51] How and why Mark adapts his material is unclear. Smith believes that Mark has adapted two separate traditions of resurrection and disappearance into one Easter narrative.[52]

Empty tomb and resurrection appearances

According to Rudolf Bultmann, "Easter stories [...] fall into two groups – stories of the empty tomb and stories of the appearance of the risen Lord, though there are stories that combine them both (Mt 28:1–8, 9f; Jn 20:1, 11–18)."[citation needed] N. T. Wright emphatically and extensively argues for the reality of the empty tomb and the subsequent appearances of Jesus, reasoning that as a matter of "inference"[53] both a bodily resurrection and later bodily appearances of Jesus are far better explanations for the empty tomb and the 'meetings' and the rise of Christianity than are any other theories, including those of Ehrman.[53][54] Dale Allison has argued for an empty tomb, that was later followed by visions of Jesus by the Apostles and Mary Magdalene, while also accepting the historicity of the resurrection.[55] Christian biblical scholars have used textual critical methods to support the historicity of the tradition that "Mary of Magdala had indeed been the first to see Jesus," most notably the Criterion of Embarrassment in recent years.[56][57] According to Dale Allison, the inclusion of women as the first witnesses to the risen Jesus "once suspect, confirms the truth of the story."[58]

According to Géza Vermes, the empty tomb developed independently from the post-resurrection appearances, as they are never directly coordinated to form a combined argument.[59] While the coherence of the empty tomb narrative is questionable, it is "clearly an early tradition".[59] Vermes rejects the literal interpretation of the story,[60] and also notes that the story of the empty tomb conflicts with notions of a spiritual resurrection. According to Vermes, "[t]he strictly Jewish bond of spirit and body is better served by the idea of the empty tomb and is no doubt responsible for the introduction of the notions of palpability (Thomas in John) and eating (Luke and John)."[61] New Testament historian Bart D. Ehrman rejects the story of the empty tomb, and argues that "an empty tomb had nothing to do with [believe in the resurrection] [...] an empty tomb would not produce faith".[62] Ehrman argues that the empty tomb was needed to underscore the physical resurrection of Jesus.[63]

- Ehrman 1999, p. 24.

- Licona, Mike (2017). Why Are There Differences In The Gospels: What We Can Learn From Ancient Biography. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 170, 184. ISBN 978-0190264260.

- Reddish 2011, p. 13,42.

- Goodacre 2001, p. 56.

- Levine 2009, p. 6.

- Perkins 1998, p. 241.

- Reddish 2011, pp. 108, 144.

- Lincoln 2005, p. 18.

- Adams 2012, p. unpaginated.

- Evans 2009, p. 1246.

- Osiek 2001, p. 206.

- Harrington 1991, p. 413.

- Evans 2011, p. unpaginated.

- Bauckham 2008, p. 138.

- Osiek 2001, p. 211.

- Alsup 2007, p. 93.

- Osborne 2004, p. 41.

- Edwards 2002, p. 493.

- Osborne 2004, p. 38.

- Osborne 2004, p. 40.

- France 2007, p. 407.

- Osiek 2001, p. 207.

- Osiek 2001, p. 209.

- Osiek 2001, p. 208.

- Osborne 2004, p. 79.

- Osborne 2004, p. 66.

- Elliott & Moir 1995, p. 43.

- Sandnes & Henriksen 2020, p. 140.

- Moss, Candida R. “Heavenly Healing: Eschatological Cleansing and the Resurrection of the Dead in the Early Church.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion, vol. 79, no. 4, 2011, pp. 995".

- Wright, N.T. “Jesus' Resurrection and Christian Origins.” Gregorianum, vol. 83, no. 4, 2002, pp. 616.

- Johnston, Sarah Iles. “Many (Un) Happy Returns: Ancient Greek Concepts of a Return from Death and Their Later Counterparts.” Coming Back to Life: The Permeability of Past and Present, Mortality and Immortality, Death and Life in the Ancient Mediterranean, edited by Frederick S. Tappenden and Carly Daniel-Hughes, by Bradley N. Rice, 2nd ed., McGill University Library, Montreal, 2017, pp. 31–32.

- Endsjø 2009, p. 102.

- Henze 2017, p. 151.

- Goodacre, Mark (2021). "How Empty Was the Tomb?". Journal for the Study of the New Testament. 44 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1177/0142064X211023714. S2CID 236233486.

- MacGregor, Kirk Robert (2018). "The ending of the pre-Markan passion narrative". Scriptura. 117. Stellenbosch University: 1–11. doi:10.7833/117-1-1352 (inactive 31 January 2024). hdl:10520/EJC-13fb46c0d3. ISSN 2305-445X.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2024 (link) - Smith 2010, p. 76.

- Smith, D. (2014). ‘Look, the place where they put him’ (Mk 16:6): The space of Jesus’ tomb in early Christian memory. HTS Teologiese Studies / Theological Studies, 70(1), 8 pages

- Harrington 2004, pp. 54–55.

- Smith 2010, p. 61.

- Miller, Richard C (2010). "Mark's Empty Tomb and Other Translation Fables in Classical Antiquity". Journal of Biblical Literature. 129 (4): 759–776. doi:10.2307/25765965. JSTOR 25765965.

- Allison 2021, pp. 156–157, n. 232.

- Ehrman (2014), p. 88.

- Rausch 2003, p. 115.

- Allison 2005, p. 306.

- Resurrection in Paganism and the Question of an Empty Tomb in 1 Corinthians 15. Journal for New Testament Studies., pp. 56-58, John Granger Cook

- The Resurrection of Jesus in the Pre-Pauline Formula of 1 Cor 15.3–5. Journal for New Testament Studies, p.498, James Ware

- Engelbrecht, J. “The Empty Tomb (Lk 24:1–12) in Historical Perspective.” Neotestamentica, vol. 23, no. 2, 1989, p. 245.

- Smith 2010, pp. 179–180.

- Wright 2003, p. 711.

- Wright, Tom (2012). The Resurrection of the Son of God. SPCK. ISBN 978-0281067503.

- Allison 2021, pp. 3, 337, 353.

- Dunn 2003b, pp. 843.

- Richard Bauckham, Gospel Women, Studies of the Named Women in the Gospels (2002), pages 257-258

- Allison 2005, pp. 327–328.

- Vermes 2008a, p. 142.

- Vermes 2008a, p. 143.

- Vermes 2008a, p. 148.

- Ehrman 2014, p. 98.

- Ehrman 2014, p. 90.

- Adams, Edward (2012). Parallel Lives of Jesus: Four Gospels – One Story. SPCK. ISBN 978-0281067725.

- Allison, Dale C. Jr. (2005). Resurrecting Jesus: The Earliest Christian Tradition and Its Interpreters. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0567397454.

- Allison, Dale C. Jr. (2021). The Resurrection of Jesus: Apologetics, Polemics, History. New York: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0567697578.

- Alsup, John E. (2007). The Post-Resurrection Appearance Stories of the Gospel Tradition: A History-of-Tradition Analysis. Wipf and Stock. ISBN 978-1597529709.

- Aune, David (2013). Jesus, Gospel Tradition and Paul in the Context of Jewish and Greco-Roman Antiquity. Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 978-3161523151.

- Bauckham, Richard (2008). "The Fourth Gospel as the Testimony of the Beloved Disciple". In Bauckham, Richard; Mosser, Carl (eds.). The Gospel of John and Christian Theology. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0802827173.

- Brown, R.E. (1973). The Virginal Conception and Bodily Resurrection of Jesus. Paulist Press. ISBN 978-0809117680.

- Dunn, James D. G. (1985). The Evidence for Jesus. Westminster John Knox. ISBN 978-0664246983.

- Dunn, James D.G. (2003b), Jesus Remembered: Christianity in the Making, Volume 1, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing

- Edwards, James (2002). The Gospel According to Mark. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0851117782.

- Ehrman, Bart (1999). Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199839438.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (2003), Lost Christianities: The Battles for Scripture and the Faiths We Never Knew, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0199727124

- Ehrman, Bart (2014), How Jesus Became God. The Exaltation of a Jewish Preacher from Galilea, Harperone

- Elliott, Keith; Moir, Ian (1995). Manuscripts and the Text of the New Testament: An Introduction for English Readers. A&C Black. ISBN 978-0567292988.

- Endsjø, D. (2009). Greek Resurrection Beliefs and the Success of Christianity. Springer. ISBN 978-0230622562.

- Evans, Craig A. (2011). Luke. Baker Books. ISBN 978-1441236524.

- Evans, Mary J. (2009). The Women's Study Bible: New Living Translation Second Edition. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195291254.

- France, R.T (2007). The Gospel of Matthew. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0802825018.

- Goodacre, Mark (2001). The Synoptic Problem: A Way Through the Maze. A&C Black. ISBN 978-0567080561.

- Harrington, Daniel J. (2004). What Are they Saying About Mark?. Paulist Press. ISBN 978-0809142637.

- Harrington, Daniel J. (1991). The Gospel of Matthew. Liturgical Press. ISBN 978-0814658031.

- Henze, Matthias (2017). Mind the Gap: How the Jewish Writings between the Old and New Testament Help Us Understand Jesus. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-1506406435.

- Levine, Amy-Jill (2009). "Introduction". In Levine, Amy-Jill; Allison, Dale C. Jr.; Crossan, John Dominic (eds.). The Historical Jesus in Context. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1400827374.

- Lincoln, Andrew (2005). Gospel According to St John. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1441188229.

- Magness, Jodi (2005). "Ossuaries and the Burials of Jesus and James". Journal of Biblical Literature. 124 (1): 121–154. doi:10.2307/30040993. ISSN 0021-9231. JSTOR 30040993.

- Mccane, Byron (2003). Roll Back the Stone: Death and Burial in the World of Jesus. A&C Black.

- Mettinger, Tryggve N. D. (2001). The Riddle of Resurrection: "Dying and Rising Gods" in the Ancient Near East. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell International. ISBN 978-9122019459.

- Osborne, Kenan (2004). The Resurrection of Jesus: New Considerations for Its Theological Interpretation. Wipf and Stock. ISBN 978-1592445875.

- Osiek, Carolyn (2001). "The Women at the Tomb". In Levine, Amy-Jill; Blickenstaff, Marianne (eds.). A Feminist Companion to Matthew. Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 9781841272115.

- Park, Eung Chun (2003). Either Jew Or Gentile: Paul's Unfolding Theology of Inclusivity. Westminster John Knox. ISBN 978-0664224530.

- Perkins, Pheme (1998). "The Synoptic Gospels and the Acts of the Apostles: Telling the Christian Story". In Barton, John (ed.). The Cambridge companion to biblical interpretation. Westminster John Knox. ISBN 978-0521485937.

- Rausch, Thomas P. (2003). Who is Jesus?: An Introduction to Christology. Liturgical Press. ISBN 978-0814650783.

- Reddish, Mitchell (2011). An Introduction to The Gospels. Abingdon Press. ISBN 978-1426750083.

- Sandnes, Karl Olav; Henriksen, Jan-Olav (2020). Resurrection: Texts and Interpretation, Experience and Theology. Wipf and Stock. ISBN 978-1532695896.

- Seesengood, Robert; Koosed, Jennifer L. (2013). Jesse's Lineage: The Legendary Lives of David, Jesus, and Jesse James. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-0567515261.

- Smith, Daniel A. (2010). Revisiting the Empty Tomb: The Early History of Easter. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-0800697013.

- Vermes, Geza (2008a), The Resurrection, London: Penguin, ISBN 978-0141912639

- Wright, N.T. (2003), The Resurrection of the Son of God, Minneapolis: Fortress Press, ISBN 978-0800626792

- Crossan, John Dominic (2009). Who Killed Jesus?. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0061978364.

- Ehrman, Bart (2014). How Jesus Became God. The Exaltation of a Jewish Preacher from Galilea. Harperone. ISBN 978-0062252197.

- Fredriksen, Paula (2008). From Jesus to Christ: The Origins of the New Testament Images of Jesus. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0281067725.

- Ludemann, Gerd (1995). What Really Happened to Jesus: A Historical Approach to the Resurrection. Westminster John Knox. ISBN 978-0664256470.

- Vermes, Geza (2008). The Resurrection. Penguin. ISBN 978-0141912639.