Hungarian_raid_in_Spain_(942)

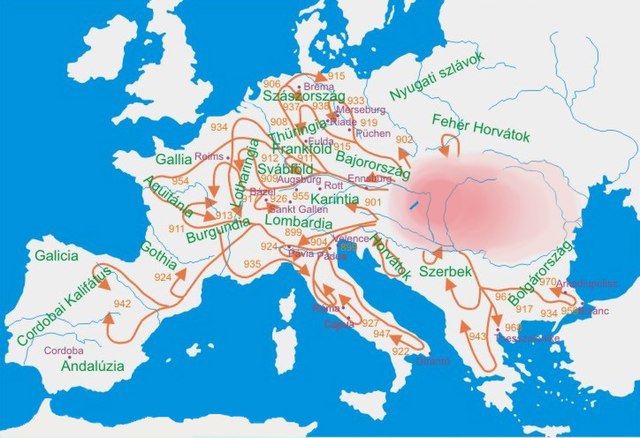

A Hungarian raid in Spain took place in July 942. This was the furthest west the Hungarians raided during the period of their migration into central Europe; although, in a great raid of 924–25, the Hungarians sacked Nîmes and may have got as far as the Pyrenees.[1]

The only contemporary reference to the Hungarians crossing the Pyrenees into Spain is in al-Maʿsūdī, who wrote that "their raids extend to the lands of Rome and almost as far as Spain".[2] The only detailed description of the raid of 942 was preserved by Ibn Ḥayyān in his Kitāb al-Muqtabis fī tarīkh al-Andalus (He Who Seeks Knowledge About the History of al-Andalus), which was finished shortly before his death in 1076. His account of the Hungarians relies on a lost tenth-century source.[3] According to Ibn Ḥayyān, the Hungarian raiding party passed through the Kingdom of the Lombards (northern Italy) and then through southern France, skirmishing along the way. They then invaded Thaghr al-Aqṣā ("Furthest March"), the northwestern frontier province of the Caliphate of Córdoba. On 7 July 942, the main army began the siege of Lleida (Lérida). The cities of Lleida, Huesca and Barbastro were all ruled by members of the Banū Ṭawīl family. The first two were ruled by Mūsa ibn Muḥammad, while Barbastro was under the control of his brother, Yaḥyā ibn Muḥammad. While besieging Lleida, the Hungarian cavalry raided as far as Huesca and Barbastro, where they captured Yaḥyā in a skirmish on 9 July.

The one who reported their matters said that their land is in the far east, and that the Pechenegs neighbour them to the east, that the land of Rome is in the direction of Mecca from them, and that the land of Constantinople is a little bit off to the east from them. To their north is the city of Moravia and the other cities of the Slavs. To the west of them are the Saxons and the Franks. To get to the land of Andalusia they traversed a long distance [a part of which is] desert ... Their way during their march crossed Lombardy, which borders them. There is a distance of eight days between them and Lombardy. Their dwelling places are on the Danube River and they are nomads as the Arabs without towns and houses living in felt tents in scattered halting-places ...[lower-alpha 1][lower-alpha 2] proceeding from the Frankish country, after defeating whomever they found during their passage, attaining the height before Lérida, at the extreme end of the March, on Thursday, ten nights remaining in the month of sawwal; the advances of their cavalry put them in the plain of the valley of Ena, Cerratania and the city of Huesca; and on Saturday, the third day of their encampment, they made captive Yaḥyā ibn Muḥammad ibn aṭ-Ṭawīl, lord of Barbastro.[lower-alpha 3]

Ibn Ḥayyān also names seven Hungarian "leaders"—the word amīr being a generic term for a ruler or governor: "They possessed seven chieftains. Among these the greatest in dignity was called Djila (Gyula). Ecser followed him, after him Bulcsudi, then Bašman, Alpár, Glad and lastly Harhadi."[6][lower-alpha 4] It has been proposed that these were the commanders of the seven contingents that made up the invading army,[8][9] but it is far more likely that Ibn Ḥayyān is merely recording the seven chieftains of the Hungarian tribes. He is perhaps relying on a Byzantine source.[6][10] In later tradition, Alpár and Glad were remembered as defeated enemies of the Hungarians. György Györffy argues that a "reshuffling of power" after 942 caused them to be remembered this way.[6]

The information about the location of Hungary, its leaders and the route of the invading army may have come from five captured Hungarians who, according to Ibn Ḥayyān, converted to Islam and were incorporated into the caliphal guard. Yaḥyā paid a large ransom and was released on 27 July. He subsequently went to Córdoba to do homage to Caliph ʿAbd ar-Rahmān III an-Nasir:

Afterwards they [the captives] became Muslims and he included them in his service. From far Tortosa came notice on the first day of the month of muḥarram the following year 331[lower-alpha 5] [14 September 942] of the rescue of Yaḥyā ibn Muḥammad ibn aṭ-Ṭawīl from the hands of these Turks through a large sum that he paid them, with which God relieved his situation on Wednesday, the tenth of ḏū l-qaʿdah [27 July 942], [after which] he went to the capital to renew his homage to an-Nasir.[lower-alpha 6]

Lacking food stores and finding insufficient forage, the Hungarians retired after a few days. According to Ibn Ḥayyān, it was the news of the raids and the fear they spread among Muslims that inspired King Ramiro II of León to repudiate the treaty he had made with the caliph the year before (941):[12]

When the enemy of God, Ramiro Ordóñez, learned of the appearance of the Turks in the march of Lérida and of the fear of the Muslims of that region, he endeavoured to profit—violating the promises that he had solemnly sworn before the bishops and monks, [thus] limiting the pretexts he could have before the dignitaries of his own religion—by sending the lord of Castile [Qaštlīya], Fernán González [Ibn Gundišalb], with a trained army in support of his son-in-law, García Sánchez, lord of Pamplona, in the war against the Muslims.[lower-alpha 7]

In fact, Count Fernán González, who commanded the border region of Castile, was cooperating with King García Sánchez I of Pamplona in the latter's war with the Caliphate as early as April, months before the Hungarians' arrival. Ramiro's real motivation was probably to prevent a loss of face, since he was married to Urraca, García's sister.[12]

Sometime between 939 and 943, Ermengol, the eldest son of Sunyer, Count of Barcelona, "died in battle at Baltarga childless" (apud Baltargam bello interfectus sine filio) according to the 12th-century Gesta Comitum Barchinonensium. The historian Albert Benet i Clará has suggested that this battle, which is otherwise unknown, must have been against the Hungarians.[14]