King's_Cross_railway_accident

The King's Cross railway accident occurred on 4 February 1945, at London King's Cross railway station on the East Coast Main Line of the London & North Eastern Railway. Two passengers were killed and 25 injured, as well as the train attendant.

| King's Cross railway accident | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Details | |||

| Date | 4 February 1945 18:11 | ||

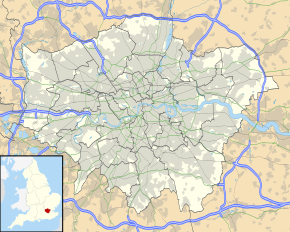

| Location | London King's Cross railway station | ||

| Country | England | ||

| Line | East Coast Main Line | ||

| Operator | London and North Eastern Railway | ||

| Cause | Mishandling of engine by driver | ||

| Statistics | |||

| Trains | 1 | ||

| Deaths | 2 | ||

| Injured | 26 | ||

| |||

| List of UK rail accidents by year | |||

The situation

The exit from Kings Cross station is through Gasworks Tunnel, which has three bores, each of which had two tracks at the time of the accident. The centre bore had the No. 1 down main line on its western side, and the up relief line on its eastern side. Trains from platforms 5, 6 or 7[1] gained the no. 1 down main line via a crossover from the up relief line, which was controlled by points no. 145. One end of this crossover was inside the tunnel. When points 145 were "reversed", the no. 1 down main line could be reached from platforms 5, 6 or 7; when points 145 were "normal", this line was reached from platforms 8 to 17. The signal box controlling this was situated at the end of platforms 5 & 6.[2]

The track is level through platform 5; it then dips at 1 in 100 (1%) for 146 yards (134 m), to a point 51 yards (47 m) inside the tunnel, where the line passes beneath Regent's Canal; it then rises at a gradient of 1 in 105 (0.95%) through the tunnel for a total of 1.25 miles (2.01 km).[2] Because of the gradient in the tunnel, it had been the practice since December 1943 for heavy trains to be assisted for the first 100 yards (91 m) by being propelled by the locomotive which had hauled the empty coaches into the platform.[3]

During the night and morning of 3–4 February 1945, the worn rails of no. 1 down main line had been replaced with new ones as part of routine maintenance; this line had been in use since 12:45 on 4 February.[4] The newly laid rails had lower adhesion, and the first (empty) train to travel on them slipped to a stand on the incline.[5]

The train

On 4 February 1945, the 18:00 service from Kings Cross to Leeds was formed of 17 coaches hauled by locomotive no. 2512 Silver Fox.[3][6]

The locomotive, Class A4 4-6-2 no. 2512 Silver Fox, had been built in 1935.[7] It was in normal condition but some trouble had been experienced that day with the sanding gear.[4]

The rearmost coach was a Vestibuled Brake Composite, no. 1889,[8] which had been built at Doncaster in 1941 as part of an order for ten (authorised in 1939 against order no. 999).[9] The design, known as Diagram 314, used a steel underframe 60 feet (18 m) long, mounted on two bogies each having a wheelbase of 8 ft 6 in (2.59 m), spaced at 43-foot (13 m) centres. The body was 61 feet 6 inches (18.75 m) long, 9 ft 3 in (2.82 m) wide, and built largely of wood, principally teak.[10] It consisted of two first-class compartments in the centre seating six each, flanked on one side by three third-class compartments also seating six each, and on the other side by a brake section for the guard. There was a side corridor, and unlike other pre-war designs of brake composite on the LNER, the external doors in the body sides were in vestibules close to the ends, instead of in the compartments;[11] a feature which had been gradually introduced from 1930.[12]

Events

On this occasion the train was not assisted, because the coaches had been propelled, rather than hauled, into the platform, and so there was no locomotive at the rear as was the usual arrangement.[3] The train left platform 5 at King's Cross station five minutes late, and entered Gasworks Tunnel.[13] When it reached the rising gradient at the far end of the tunnel the locomotive began to slip badly on a section of newly replaced rail. In the absence of an assisting locomotive and with its own sanding equipment not working fully, no. 2512 was unable to grip the rail and eventually came to a stand. Preoccupied with his tasks at the controls and operating in darkness the driver didn't notice when the train slowed to a stop, and then began to run backwards.[3]

Meanwhile, the points behind the train (no. 145) had been set for the next departure, which was to be from Platform 10. The coaches for this service, the 19:00 Aberdonian to Aberdeen, were already in the platform.[14] The signalman became aware of the 18:00 train rolling back and operated the points again in order to route it into unoccupied platform 15, but he was too late; the first bogie of the rear coach (BCK no. 1889) had already passed. This caused the two bogies to take different tracks. The rear of the train collided with the front of the coaches in platform 10. The rear coach rose into the air and struck a signal gantry,[15][14][16] crushing one of the two first-class compartments in the middle of the coach.[13] Two passengers were killed,[3] one of whom was Cecil Kimber, the former managing director and co-founder of the MG car company.[17]

After the accident

The signal gantry demolished in the collision carried shunting discs and platform indicators in addition to main aspect signals. In an emergency measure hand signallers were introduced to control main line trains using platforms 6 to 17, as well as movements to and from the locomotive yard. Suburban services were terminated and turned round at Finsbury Park.[15][14][16]

Coach no. 1889 was so severely damaged that it was written off. It had been scheduled to be renumbered 10153, but that number then remained unused.[9]

Two weeks later, the signal gantry was replaced,[15][16] but complete services were not restored until 23 February 1945.[15][14]

The accident has variously been described as "somewhat bizarre"[3] and "stupid".[18]

The Inspecting Officer, Col. Wilson, concluded in his report that the main fault lay with the driver. Although it was difficult for him to tell which direction he was moving in the tunnel, he should have anticipated the possibility that he might roll back after the prolonged slipping. He did not realise for some minutes after the train had stopped that a collision had occurred. [4]

A similar accident occurred at Glasgow Queen Street in 1928, involving a lighter train but on a much steeper gradient.

- the present-day platforms 4, 5 & 6

- Wilson 1945, pp. 3, 14.

- Hughes 1987, p. 125.

- Wilson 1945, p. 3.

- Wilson 1945, p. 14.

- Wilson 1945, pp. 1, 3.

- Boddy, Neve & Yeadon 1973, p. 94.

- Wilson 1945, p. 2.

- Harris 1995, p. 151.

- Harris 1995, pp. 34–36, 151.

- Harris 1995, pp. 48, 151.

- Harris 1995, p. 42.

- Wilson 1945, p. 1.

- Cooke 1958, p. 512.

- The Railway Magazine 1945, p. 176.

- Bonavia 1985, p. 36.

- Boddy, M.G.; Neve, E.; Yeadon, W.B. (April 1973). Fry, E.V. (ed.). Part 2A: Tender Engines - Classes A1 to A10. Locomotives of the L.N.E.R. Kenilworth: RCTS. ISBN 0-901115-25-8.

- Bonavia, Michael R. (1985) [1983]. 3. The Last Years, 1939-48. A History of the LNER. London: Guild Publishing/Book Club Associates. CN 5280.

- Cook, Jean (1993). "The Man who Lived His Dream". In Haining, Peter (ed.). MG Log: A Celebration of the World's Favourite Sports Car. London: Souvenir Press. ISBN 0-285-63144-6.

- "Notes and News: A Collision at Kings Cross". The Railway Magazine. 91 (557). Westminster: Railway Publishing Company. May–June 1945.

- Cooke, B.W.C., ed. (July 1958). "The Why and the Wherefore: Collision at Kings Cross". The Railway Magazine. 104 (687). Westminster: Tothill Press.

- Harris, Michael (1995). LNER Carriages. Penryn: Atlantic Books. ISBN 0-906899-47-8.

- Hughes, Geoffrey (1987) [1986]. LNER. London: Guild Publishing/Book Club Associates. CN 1455.

- Wilson, G.R.S. (29 May 1945). "Report on the Accident at King's Cross on 4th February 1945". Retrieved 9 February 2010 – via The Railways Archive.