Kingdom_of_Jeypore

Jeypore Estate

Kingdom of the Kalinga region of India

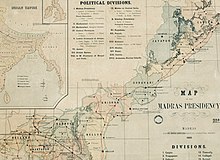

Jeypore Estate[1][2][3] or Jeypore Zamindari[2][4][5] was a Zamindari estate of the Madras Presidency in British India. Historically it was a kingdom known as Jeypore Kingdom, located in the highlands of the western interiors of the Kalinga region that existed from the mid-15th century to 1777 CE. It was earlier a tributary state of the Gajapati Empire and following its decline in 1540, it gained sovereignty and later became a tributary state of the Qutb Shahis until 1671. The kingdom regained degrees of semi-independence until it became a vassal state of the British in 1777. It eventually formed a part of the linguistic Orissa Province in 1936 upon transfer from the Madras Province[6] and became a part of the independent Union of India in 1947.[7][8][9]

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| Jeypore Estate | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kingdom of Jeypore 1443-1777 Zamindari of British India 1777-1947 | |||||||||||

| 1443–1947 | |||||||||||

Jeypore State in the Madras Presidency | |||||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||

• 1911 | 31,079 km2 (12,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||

• 1925 | 38,849 km2 (15,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

• Established | 1443 | ||||||||||

| 1947 | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | Odisha, India | ||||||||||

Origin of Silavamsa of Nandapur

The Earliest mention of the Silavamsa rulers are about a king named Ganga Raja who ruled from Nandapur. His son Viswanadha Raja or Bhairava Raja was married to princess Singamma, the daughter of Jayanta Raju of Matsya dynasty of Odda-Adi in Madugula.[10] The Matsya territory was called 'Vaddadi' (meaning beginning of the Odra Kingdom) and a small village named Vaddadi (170°50' N - 82°56' E) is found even today at the entrance of the hilly tract of Madugula which was under the possession of the Jeypore rulers.[11][12]The Machkund or Matsyakund River[13] (also called Sileru River in Andhra Pradesh) formed the border between the two kingdoms. The Silavamsa and Matsya family were connected by matrimonial alliances[14] and the Vaddadi kingdom of Matsya family was eventually destroyed by Krishna Deva Raya and absorbed into the Nandapur Kingdom.[15]

Viswanadha Raja's son Pratap Ganga Raja gave lands in Bobbili to his generals in 1427 CE. Around 1434 CE, he led an expedition up to the Bay of Bengal. As a Srikurmam temple record dated to 1435 CE states, he "washed his sword in the ocean". He would not have done this for Bhanu Deva IV, the last ruler of Eastern Ganga dynasty. He was subdued by Kapilendra Deva.[14][16]

- Ganga Raja (1353–??)

- Viswanadha Raja or Bhairava Raja

- Pratap Ganga Raja (??–1443)

Both Jainism and Saktism are known to have flourished in the Nandapur kingdom during this period and ruins of Jaina and Sakta temples are still found in the neighbourhood of the village Nandapur.[17]

Vinayak Dev and the advent of a new dynasty

Pratap Ganga Raja only had one daughter, Lilavati. She married Vinayak Dev, the ruler of Gudari and he became the ruler of Nandapur after Pratap Ganga Raja's death.[18] According to myths in the Jeypore chronicles, Vinayak Dev claimed to be the 33rd descendant of Kanakasena of Suryavansha. He was a general and feudatory of the king of Kashmir, left Kashmir for Varanasi and after praying at Kashi Vishwanath migrated to the Nandapur kingdom. But according to the study of the sign-manual at the end of a copper-plate chatter of Raghunath Krishna Dev, then ruler of Jeypore, the new dynasty was founded by one of the feudal vassals of the Gajapati of Cuttack and the crescent seal indicated that they originally claimed to be Somavanshi rulers.[19] According to Gangavamsanu Charitam, a Sanskrit work composed in 1760-61 by Vasudev Ratha,[20] Khajjala-Bhanu was the son of the last Ganga ruler of Cuttack Madhupa-Bhanu (possibly Bhanu Deva IV) and became the ruler of Gudari after Kapileshwara occupied his fathers throne. According to one theory Khajjala-Bhanu was Vinayak Dev. [21][22] Gudari was the capital of Khemundi Ganga rulers for some time[23] and according to family traditions they do claim to be Somavanshis.[24] According to other interpretations he was a Somavanshi Rajput[25] or the Nandapur kingdom was conferred to him by Kapilendra Deva, who also claimed to belong to Suryavansha, to one of the scions of Kapilendra's family as a mark of favor.[26] It is said that at the beginning he was not recognised as a ruler by a section of people who overthrew his rule and he was helped by an influential merchant named Lobinia who provided him with cavalry and infantry and also 10,000 cattle for transport, and with this help he reoccupied Nandapur and suppressed the turbulent enemies.[27][22][28]

Vijaya Chandra's successor Bhairava Dev was a feudatory of Prataprudra Deva who defended Kondapalli Fort against Krishna Deva Raya's invasion in 1516 CE and constructed a reservoir called Bhairava Sagar in Bobbili. His successor Vishwanath Dev Gajapati shifted his capital to Rayagada for better economic prospects in trade and agriculture and built a mud fort. He also constructed many temples along Nagavali River including the Majhighariani Temple. During his reign Shri Chaitanya migrated southwards and the title of Nauna Gajapati[29] or "no less than a Gajapati" was adopted by the royal dynasty of Nandapur, but after the accession of Govinda Vidyadhara he seems to have submitted to the sovereign authority of the Bhoi dynasty.[30][31]

Under Qutb Shahi dynasty

In 1565, the dynasty that had previously succeeded in forcing several "little kings" to be tributaries was itself forced into tributary status by the Shah of Golkunda.[32]

In the mid-17th century, Maharajah Veer Vikram Dev, the eighth king, founded the city of Jeypore and moved his capital there.[33] This move is recorded as taking place because astrologers had determined that the reason each of the preceding six rulers had each fathered only one son was because Nandapur was cursed; however, Schnepel notes that the gradual movement of Muslim invaders from Coastal Andhra into Orissa probably influenced the decision.[34] He died in 1669 and was succeeded by his only son, Krishna Dev.[35]

Narayanapatna was the capital for several rulers, including Vishwambhara Dev II (r. 1713–1752), whom the later panegyrist of the family (himself a member by marriage) said was an ardent follower of the Vaishnavite teachings of Chaitanya. That bhakti sect, which remains popular in Orissa to this day, formed a significant bond between the royal family and their Khond tribal subjects. The bond, however, could be tenuous and the dynasty ruled by consent of their notional subjects. Although the dynasty could rely on support from tribal warriors at times, Schnepel notes, as an example of shaky authority, the unrest in the "quasi-royal estate ... or 'little little kingdom'" of Kalyansingpur. There the Khond people at one point sought to take advantage of a dispute over succession to appeal to the zamindari to appoint a king more local and approachable than the rulers at Jeypore.[36][lower-alpha 1] Schnepel notes of Bissam Cuttack, which was another area within the dynastic realm, that "powerful local rulers ... held a position which was nominally subordinate to the Jeypore kings but in fact was held independently of them".[34]

British India

Jeypore covered an area of around 10,000 sq mi (26,000 km2) and was assessed to pay a tribute of 16,000 rupees in the 1803 permanent settlement. Vikram Dev I (r. 1758–1781) had joined other minor kings of the region in military opposition to the British colonial influence, leading to an attack by the British in 1775 which destroyed the fort at Jeypore. His son, Rama Chandra Dev II (r. 1781–1825) reversed the strategy, preferring co-operation to resistance and was favoured by the British for that reason. An additional factor in the vastly improved status of the dynasty was that the British fell out with Vizianagaram, another minor kingdom and long a rival of Jeypore. Flushed with confidence, Rama Chandra Dev arranged for a new capital and palace to be built at Jeypore, some distance away from the ruined fort.[34]

Vikram Dev III (1889–1920), also known as His Highness Maharajah Sir Sri Sri Vikram Dev, was aged 14 when his father died, and he could not legally assume his responsibilities as ruler until he turned 28. His father had made arrangements for his education to be continued by a Dr. Marsh until that time. He was appointed a Knight Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire (KCIE) and granted the title of His Highness for use by him and his successors.[when?] The British Raj granted him and his successors the right, from 1896, to use the title Maharajah, which was originally held by his ancestors.[clarification needed] In 1893, he was married to the princess of Surguja State. He laid the foundation of the new palace known as Moti Mahal and was a liberal philanthropist, donating to many institutions that helped the public. He funded the construction of bridges over the Kolab and Indravati rivers. He died in 1920.[citation needed]

Ramchandra Dev IV (1920–1931), also known as His Highness Lieutenant Maharajah Ramchandra Dev, ascended the throne in 1920. He received the rank of a Lieutenant for his aid in the First World War by sending his navy's twelve ships and a small unit of his troops. The king died in Allahabad in 1931 without any issue and was succeeded by his uncle, who was also named Vikram Dev. Although he died unexpectedly and young, he is known for building the grand Hawa Mahal, or the Palace of Winds, on the beach of Visakhapatnam.[38]

Vikram Dev IV (1931–1951), known as Sahitya Samrat HH Maharajah Vikram Dev, was crowned as the last king of the kingdom in 1931. He was a scholar, poet, playwright and leader. Being a prolific writer and proficient in five different languages—Telugu, Odia, Hindi, Sanskrit, and English—he earned the literary epithet of Sahitya Samrat, meaning the "Emperor of Literature", and a doctorate degree (D.Litt.) from Andhra University. He donated large amounts to Andhra University and served as the vice-chancellor of Andhra and Utkal universities. He married his daughter to an aristocratic family of Bihar and had his son-in-law Kumar Bidyadhar Singh Deo look after the affairs of his kingdom. His daughter gave birth to two sons and, as per traditional vedic rule, which suggests that the younger son belongs to the mother, eventually Ram Krishna Dev, being the younger prince, was appointed as the crown prince. He was the last king, as the kingdom merged into the newly formed Union of India.[39]

Post-independence India

Ram Krishna Dev was the last king of the estate, as the titles were abolished in independent India soon after its creation with the first amendment to the constitution of India which amended the right to property as shown in Articles 19 and 31.[40][41]

Ram Krishna Dev (1951–2006) became the titular king of Jeypore at his coronation in 1951, following the death of his grandfather. He married Rama Kumari Devi of Sitamau State, in Malwa, and had three children: a daughter, Maharajakumari Maya Vijay Lakshmi; and two sons, Yuvraj Shakti Vikram Dev and Rajkumar Vibhuti Bhusan Dev. The senior prince was married to Mayank Devi and had a daughter named Lalit Lavang Latika Devi; the junior prince was married to Sarika Devi of Nai Garhi royalty and had a son named Vishweshwar Chandrachud Dev. However, after the untimely deaths of both princes in 1997 and 2006, respectively, the right to the throne was disputed.[42]

On 14 January 2013, Vishweshvar Dev was crowned as the Pretending Maharaja of Jeypore. The coronation took place on the auspicious day of Makar Sankranti and the royal rituals were performed by Bisweswar Nanda, a descendant of the early Raj Purohit lineage. On days of cultural importance and festivals, Vishweshvar appears as the Maharaja and conducts the royal ceremonial duties at Dussehra and Ratha Yatra.[43]

The royal genealogical table of Jeypore mentions 25 kings.[44]

1443–1675 (from Nandapur and Rayagada)

| Name | Reign began | Reign ended | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Vinayak Dev | 1443 | 1476 |

| 2 | Vijaya Chandra | 1476 | 1510 |

| 3 | Bhairava Dev | 1510 | 1527 |

| 4 | Vishwanath Dev Gajapati | 1527 | 1571 |

| 5 | Balaram Dev I | 1571 | 1597 |

| 6 | Yashasvan Dev | 1597 | 1637 |

| 7 | Krishna Raj Dev | 1637 | 1637 |

1675–1947 (from Jeypore)

| Name | Reign began | Reign ended | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | Veer Vikram Dev | 1637 | 1669 |

| 9 | Krishna Dev | 1669 | 1672 |

| 10 | Vishwambhar Dev | 1672 | 1676 |

| 11 | Malakimardhan Krishna Dev | 1676 | 1681 |

| 12 | Hari Dev | 1681 | 1684 |

| 13 | Balaram Dev II | 1684 | 1686 |

| 14 | Raghunath Krishna Dev | 1686 | 1708 |

| 15 | Ram Chandra Dev I | 1708 | 1711 |

| 16 | Balaram Dev III | 1711 | 1713 |

| 17 | Vishwambhar Dev II | 1713 | 1752 |

| 18 | Lala Krishna Dev | 1752 | 1758 |

| 19 | Maharajah Vikram Dev I | 1758 | 1781 |

| 20 | Ram Chandra Dev II | 1781 | 1825 |

| 21 | Maharajah Vikram Dev II | 1825 | 1860 |

| 22 | Ram Chandra Dev III | 1860 | 1889 |

| 23 | Vikram Dev III | 1889 | 1920 |

| 24 | Ram Chandra Dev IV | 1920 | 1931 |

| 25 | Vikram Dev IV | 1931 | 1951 |

| 26 | Ram Krishna Dev (titular) (pretender) | 1951 | 2006 |

| 27 | Vishweshvar Dev (pretender) | 2013 | |

Notes

- The date of this incident is unclear. There appears to be either a typographical error in Schnepel's writing or in the Raj gazetteer upon which he relies.[37]

Citations

- Nanda, Chandi Prasad (1997), "MOBILISATION, RESISTANCE AND POPULAR INITIATIVES: Locating The Tribal Perception Of Swaraj In The Jeypore Estate Of Orissa (1937-38)", Indian History Congress, 58: 543–554, JSTOR 44143959,

Jeypore Estate Of Orissa

- Pati, Biswamoy (1980), "Storm over Malkangiri : A Preliminary Note on Laxman Naiko's Revolt(1942)", Indian History Congress, 41: 706–721, JSTOR 44141897,

Jeypore Estate

- "Ramakrishna Deo vs Collector Of Koraput And Anr. on 14 November, 1956". Indian Kanoon. 14 November 1956.

Jeypore Estate

- "CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY OF INDIA DEBATES (PROCEEDINGS)- VOLUME III" (PDF). Lok Sabha. 2 May 1947. p. 11.

Jeypore Zamindari

- "Maharaja Of Jeypore vs Rukmini Pattamahadevi on 12 January, 1919". Indian Kanoon. 12 January 1919.

Jeypore Zamindari

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Madras (presidency)" . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 290.

- MaClean, C. D. (1877). Standing Information regarding the Official Administration of Madras Presidency. Government of Madras.

- Delhi, American Libraries Book Procurement Center, New (1970). Accessions List, India. American Libraries Book Procurement Center. p. 461. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Sciences, Indian Academy of (1949). Proceedings of the Indian Academy of Sciences. Indian Academy of Sciences. p. 35.

- Datt, Senapati & Sahu 2016, p. 36-37.

- Datt 2016a, p. 42.

- Datt 2016b, p. 29.

- The Deccan Geographer Volume 7. Secunderabad: The Deccan Geographical Society. 1969. p. 49. ASIN B000ITU2M4.

- Datt 2016b, p. 32.

- Datt, Senapati & Sahu 2016, p. 37.

- Datt, Senapati & Sahu 2016, p. 88-99, 37.

- Datt, Senapati & Sahu 2016, p. 38.

- Ramdas 1931, p. 8-12, 10.

- Das, G.S. (1953). "The Date of Composition of Gangavamsanu Charitam Champu Kavyam and the Genealogy of its Author". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 16. Indian History Congress: 281–283. JSTOR 44303891.

- Ramdas 1931, p. 12.

- Datt, Dr. Tara (2016c). Odisha District Gazetteers: Gajapati (PDF). Bhubaneshwar: Gopabandhu Academy of Administration. pp. 2, 52.

- Datt 2016c, pp. 4, 52.

- Carmichael, David Freemantle (1869). "Chapter VII - CIVIL DIVISIONS: Section I - Ancient Zamindari Families and Estates: No. 2 - The "Jeypore" family and Estate". A Manual of the District of Vizagapatam, in the Presidency of Madras. The Asylum Press. ISBN 978-1013731358.

- Datt, Senapati & Sahu 2016, p. 37-38.

- Datt, Senapati & Sahu 2016, p. 40.

- Vadivelu, A (1915). The Ruling Chiefs, Nobles and Zamindars of India. G.C. Loganadham. p. 458.

- Datt 2016b, p. 304.

- Datt, Senapati & Sahu 2016, p. 39.

- Mohanty 2013, p. 2.

- "History | Koraput District, Government Of Odisha | India". Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- Datt 2016a, p. 43.

- Schnepel 2020, pp. 198–200.

- Schnepel 2020, pp. 198–199.

- Mahalik, Nirakar. "Vikram Dev Verma" (PDF). Magazines.odisha.gov.in. Odisha Magazine. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- Guha, Ramachandra (2011). India After Gandhi. Ecco. pp. 219–220. ISBN 978-0-330-54020-9.

- Ramusack, Barbara N. (2004). The Indian princes and their states. Cambridge University Press. p. 278. ISBN 978-0-521-26727-4. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- "Jeypore hails its new 'lord'". The Times of India. 15 January 2013. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- Datt 2016a, p. 45.

Bibliography

- Schnepel, Burkhard (1995), Durga and the King: Ethno-historical Aspects of Politico-Ritual Life in a South Orissan Kingdom, Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, ISBN 978-81-86772-17-1, JSTOR 3034233

- Schnepel, Burkhard (2020) [2005], "Kings and Tribes in East India: the Internal Political Dimension", in Quigley, Declan (ed.), The Character of Kingship, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-8452-0290-3

- Mohanty, Indrajit (2013). Jeypore - A Historical Perspective (PDF). Government of Odisha State.

- Datt, Dr. Tara (2016a), Odisha District Gazetteers: Nabarangapur (PDF), Bhubaneshwar: Gopabandhu Academy of Administration

- Datt, Dr. Tara (2016b), Odisha District Gazetteers: Rayagada (PDF), Bhubaneshwar: Gopabandhu Academy of Administration

- Devi, Yashoda (1933). "Chapter XIII - The Dynasties in South Kalinga: Part 33-40". The history of Andhra country (1000 AD - 1500 AD). Gyan Publishing House. ISBN 81-212-0438-0.

- Datt, Dr. Tara; Senapati, Dr. Nilamani; Sahu, Sri Nabin Kumar (2016). Orissa District Gazetteers: Koraput (PDF). Bhubaneshwar: Gopabandhu Academy of Administration.

- Ramdas, G. (July 1931). "The Kechala Copper-Plate Grant of Krishnadeva". Journal Of The Andhra Historical Research Society Volume 6 Part 1. Rajahmundry: Andhra Historical Research Society.

- Schnepel, Burkhard (2002). The Jungle Kings: Ethnohistorical Aspects of Politics and Ritual in Orissa. Manohar. ISBN 978-81-7304-467-0.

- Rousseleau, Raphael (2009). "The King's Elder Brother: Forest King and "Political Imagination" in Southern Orissa". Rivista di Studi Sudasiatici. 4: 39–62. doi:10.13128/RISS-9116.