Languages_of_South_Africa

At least thirty-five languages are spoken in South Africa, twelve of which are official languages of South Africa: Ndebele, Pedi, Sotho, South African Sign Language, Swazi, Tsonga, Tswana, Venda, Afrikaans, Xhosa, Zulu and English, which is the primary language used in parliamentary and state discourse, though all official languages are equal in legal status. In addition, South African Sign Language was recognised as the twelfth official language of South Africa by the National Assembly on 3 May 2023.[2] Unofficial languages are protected under the Constitution of South Africa, though few are mentioned by any name.

| Languages of South Africa | |

|---|---|

Dominant languages in South Africa:

| |

| Official | |

| Recognised |

|

| Main | English |

| Signed | South African Sign Language |

| Keyboard layout | |

Unofficial and marginalised languages include what are considered some of Southern Africa's oldest[according to whom?] languages: Khoekhoegowab, !Orakobab, Xirikobab, N|uuki, ǃXunthali, and Khwedam; and other African languages, such as SiPhuthi, IsiHlubi, SiBhaca, SiLala, SiNhlangwini (IsiZansi), SiNrebele (SiSumayela), IsiMpondo/IsiMpondro, IsiMpondomise/IsiMpromse/Isimpomse, KheLobedu, SePulana, HiPai, SeKutswe, SeṰokwa, SeHananwa, SiThonga, SiLaNgomane, SheKgalagari, XiRhonga, SeKopa (Sekgaga), and others. Most South Africans can speak more than one language,[3] and there is very often a diglossia between the official and unofficial language forms for speakers of the latter.

The most common language spoken as a first language by South Africans is Zulu (23 percent), followed by Xhosa (16 percent), and Afrikaans (14 percent). English is the fourth most common first language in the country (9.6%), but is understood in most urban areas and is the dominant language in government and the media.[4]

The majority of South Africans speak a language from one of the two principal branches of the native Bantu languages that are represented in South Africa: the Sotho–Tswana branch (which includes Southern Sotho, Northern Sotho and Tswana languages officially), or the Nguni branch (which includes Zulu, Xhosa, Swati and Ndebele languages officially). For each of the two groups, the languages within that group are for the most part intelligible to a native speaker of any other language within that group.[5]

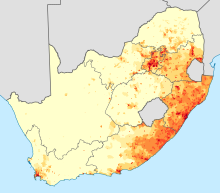

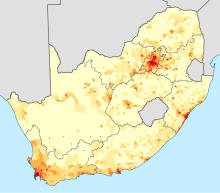

The indigenous African languages of South Africa which are official, and therefore dominant, can be divided into two geographical zones, with Nguni languages being predominant in the south-eastern third of the country (Indian Ocean coast) and Sotho-Tswana languages being predominant in the northern third of the country located further inland, as also in Botswana and Lesotho. Gauteng is the most linguistically heterogeneous province, with roughly equal numbers of Nguni, Sotho-Tswana and Indo-European language speakers, with Khoekhoe influence. This has resulted in the spread of an urban argot, Tsotsitaal or S'Camtho/Ringas, in large urban townships in the province, which has spread nationwide.

Tsotsitaal in its original form as "Flaaitaal" was based on Afrikaans, a colonial language derived from Dutch, which is the most widely spoken language in the western half of the country (Western and Northern Cape). Afrikaans is spoken as first language by approximately 61 percent of whites and 76 percent of Coloured people.[6] This racial term is popularly considered to mean "mixed race", as it represents to some degree a creole population many of whom are descendants of slave populations imported by the Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC) from slaving posts in West and East Africa, and from its colonies of the Indian Ocean trade route.

Political exiles from the VOC colony of Batavia were also brought to the Cape, and these formed a major influencing force in the formation of Afrikaans, particularly in its Malay influence, and its early Jawi literature. Primary of these was the founder of Islam at the Cape, Sheikh Abadin Tadia Tjoessoep (known as Sheikh Yusuf). Hajji Yusuf was an Indonesian noble of royal descent, being the nephew of the Sultan Alauddin of Gowa, in today Makassar, Nusantara. Yusuf, along with 49 followers including two wives, two concubines and twelve children, were received in the Cape on 2 April 1694 by governor Simon van der Stel. They were housed on the farm Zandvliet, far outside of Cape Town, in an attempt to minimise his influence on the VOC's slaves. The plan failed however; Yusuf's settlement (called Macassar) soon became a sanctuary for slaves and it was here that the first cohesive Islamic community in South Africa was established. From here the message of Islam was disseminated to the slave community of Cape Town, and this population was foundational in the formation of Afrikaans. Of particular note is the Cape Muslim pioneering of the first Afrikaans literature, written in Arabic Afrikaans, which was an adaptation of the Jawi script, using Arabic letters to represent Afrikaans for both religious and quotidian purposes. It also became the de facto national language of the Griqua (Xiri or Griekwa) nation, which was a mixed race group.

Afrikaans is also spoken widely across the centre and north of the country, as a second (or third or even fourth) language by Black or Indigenous South Africans (which, in South Africa, popularly means SiNtu-speaking populations) living in farming areas.

The 2011 census recorded the following distribution of first language speakers:[6]

Demographics

| Language | L1 speakers | L2 speakers[7] | Total speakers[7] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Of population | Count | Of population | Count | Of population | |

| Zulu | 11,587,374 | 22.7% | 15,700,000 | 27,300,000 | 46% | |

| Xhosa | 8,154,258 | 16.0% | 11,000,000 | 19,150,000 | 33% | |

| Afrikaans | 6,855,082 | 13.5% | 10,300,000 | 17,160,000 | 29% | |

| English | 4,892,623 | 9.6% | 14,000,000 | 19,640,000 | 33% | |

| Pedi | 4,618,576 | 9.1% | 9,100,000 | 13,720,000 | 23% | |

| Tswana | 4,067,248 | 8.0% | 7,700,000 | 11,770,000 | 20% | |

| Sotho | 3,849,563 | 7.6% | 7,900,000 | 11,750,000 | 20% | |

| Tsonga | 2,277,148 | 4.5% | 3,400,000 | 5,680,000 | 10% | |

| Swati | 1,297,046 | 2.5% | 2,400,000 | 3,700,000 | 6% | |

| Venda | 1,209,388 | 2.4% | 1,700,000 | 2,910,000 | 5% | |

| Ndebele | 1,090,223 | 2.1% | 1,400,000 | 2,490,000 | 4% | |

| SA Sign Language | 234,655 | 0.5% | 500,000 | |||

| Other languages | 828,258 | 1.6% | ||||

| Total | 50,961,443 | 100.0% | ||||

| Language | 2022 | 2011 | 2001 | Change 2011–2022 (pp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zulu | 24.4% | 22.7% | 23.8% | 1.3% |

| Xhosa | 16.3% | 16.0% | 17.6% | 0.3% |

| Afrikaans | 10.6% | 13.5% | 13.4% | -2.9% |

| Sepedi | 10.0% | 9.0% | 9.4% | 1.0% |

| English | 8.7% | 9.7% | 8.3% | -1.0% |

| Tswana | 8.3% | 8.0% | 8.2% | 0.3% |

| Sesotho | 7.8% | 7.6% | 7.9% | 0.2% |

| Tsonga | 4.7% | 4.5% | 4.4% | 0.2% |

| Swati | 2.8% | 2.5% | 2.7% | 0.3% |

| Venda | 2.5% | 2.4% | 2.3% | 0.1% |

| Ndebele | 1.7% | 2.1% | 1.6% | -0.4% |

| SA Sign Language | 0.02% | 0.5% | -0.4% | |

| Other languages | 2.1 | 1.6% | 0.5% | 0.5% |

| Total | 100.0% | 100.0% | 100.0% |

Other significant languages in South Africa

Other languages spoken in South Africa not mentioned in the Constitution, include many of those already mentioned above, such as KheLobedu, SiNrebele, SiPhuthi, as well as mixed languages like Fanakalo (a pidgin language used as a lingua franca in the mining industry), and Tsotsitaal or S'Camtho, an argot that has found wider usage as an informal register.

Many unofficial languages have been variously claimed to be dialects of official languages, which largely follows the Apartheid practice of the Bantustans, wherein minority populations were legally assimilated towards the official ethnos of the Bantustan or "Homeland".

Significant numbers of immigrants from Europe, elsewhere in Africa, China, and the Indian subcontinent (largely as a result of the British Indian indenture system) means that a wide variety of other languages can also be found in parts of South Africa. In the older immigrant communities there are: Greek, Gujarati, Hindi, Portuguese, Tamil, Telugu, Bhojpuri, Awadhi, Urdu, Yiddish, Italian and smaller numbers of Dutch, French and German speakers. Older Chinese tend to speak Cantonese or Hokkien, but recent immigrants mainly speak Mandarin Chinese.

These non-official languages may be used in limited semi-official use where it has been determined that these languages are prevalent. More importantly, these languages have significant local functions in specific communities whose identity is tightly bound around the linguistic and cultural identity that these non-official SA languages signal.

The fastest growing non-official language is Portuguese[8] – first spoken by immigrants from Portugal, especially Madeira[9] and later black and white settlers and refugees from Angola and Mozambique after they won independence from Portugal and now by more recent immigrants from those countries again – and increasingly French, spoken by immigrants and refugees from Francophone Central Africa.

More recently, speakers of North, Central and West Africa languages have arrived in South Africa, mostly in the major cities, especially in Johannesburg and Pretoria, but also Cape Town and Durban.[10]

Angloromani is spoken by the South African Roma minority.[11]

Chapter 1 (Founding Provisions), Section 6 (Languages) of the Constitution of South Africa is the basis for government language policy.

The English text of the constitution signed by president Nelson Mandela on 16 December 1996 uses (mostly) the names of the languages expressed in those languages themselves. Sesotho refers to Southern Sotho, and isiNdebele refers to Southern Ndebele. The Interim Constitution of 1993 referred to Sesotho sa Leboa, while the 1996 Constitution used "Sepedi" for the title of the Northern Sotho language.[12]

The constitution mentions "sign language" in the generic sense rather than South African Sign Language specifically.

- The official languages of the Republic are

- Recognising the historically diminished use and status of the indigenous languages of our people, the state must take practical and positive measures to elevate the status and advance the use of these languages.

- The national government and provincial governments may use any particular official languages for the purposes of government, taking into account usage, practicality, expense, regional circumstances and the balance of the needs and preferences of the population as a whole or in the province concerned; but the national government and each provincial government must use at least two official languages.

- Municipalities must take into account the language usage and preferences of their residents.

- The national government and provincial governments, by legislative and other measures, must regulate and monitor their use of official languages. Without detracting from the provisions of subsection (2), all official languages must enjoy parity of esteem and must be treated equitably.

- A Pan South African Language Board established by national legislation must

- promote, and create conditions for, the development and use of -

and

- all official languages;

- the Khoi, Nama and San languages; and

- sign language;

- promote and ensure respect for

— Constitution of the Republic of South Africa[13]

The following is from the preamble to the Constitution of South Africa:

| English[14] | Afrikaans[15] | isiNdebele[16] | isiXhosa[17] | isiZulu[18] | siSwati[19] | Sepedi[20] | Sesotho[21] | Setswana[22] | Tshivenda[23] | Xitsonga[24] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preamble | Aanhef | Isendlalelo | Intshayelelo | Isendlalelo | Sendlalelo | Ketapele | Ketapele | Pulamadibogo | Mvulatswinga | Manghenelo |

| We, the people of South Africa, | Ons, die mense van Suid-Afrika, | Thina, abantu beSewula Afrika, | Thina, bantu baseMzantsi-Afrika, | Thina, bantu baseNingizimu Afrika, | Tsine, bantfu baseNingizimu Afrika, | Rena, batho ba Afrika Borwa, | Rona, batho ba Afrika Borwa, | Rona, batho ba Aforika Borwa, | Riṋe, vhathu vha Afrika Tshipembe, | Hina, vanhu va Afrika Dzonga, |

| Recognise the injustices of our past; | Erken die ongeregtighede van ons verlede; | Siyakwazi ukungakaphatheki kwethu ngokomthetho kwesikhathi sakade; | Siyaziqonda iintswela-bulungisa zexesha elidlulileyo; | Siyazamukela izenzo ezingalungile zesikhathi esadlula; | Siyakubona kungabi khona kwebulungiswa esikhatsini lesengcile; | Re lemoga ditlhokatoka tša rena tša bogologolo; | Re elellwa ho ba le leeme ha rona nakong e fetileng; | Re itse ditshiamololo tsa rona tse di fetileng; | Ri dzhiela nṱha u shaea ha vhulamukanyi kha tshifhinga tsho fhelaho; | Hi lemuka ku pfumaleka ka vululami ka nkarhi lowu nga hundza; |

| Honour those who suffered for justice and freedom in our land; | Huldig diegene wat vir geregtigheid en vryheid in ons land gely het; | Sihlonipha labo abatlhoriswako ngerhuluphelo lokobana kube khona ubulungiswa netjhaphuluko enarheni yekhethu; | Sibothulel’ umnqwazi abo baye bev’ ubunzima ukuze kubekho ubulungisa nenkululeko elizweni lethu; | Siphakamisa labo abahluphekela ubulungiswa nenkululeko emhlabeni wethu; | Setfulela sigcoko labo labahlushwa kuze sitfole bulungiswa nenkhululeko eveni lakitsi; | Re tlotla bao ba ilego ba hlokofaletšwa toka le tokologo nageng ya gaborena; | Re tlotla ba hlokofaditsweng ka lebaka la toka le tokoloho naheng ya rona; | Re tlotla ba ba bogileng ka ntlha ya tshiamo le kgololosego mo lefatsheng la rona; | Ri ṱhonifha havho vhe vha tambulela vhulamukanyi na mbofholowo kha shango ḽashu; | Hi xixima lava xanisekeke hikwalaho ko hisekela vululami na ntshunxeko etikweni ra hina; |

| Respect those who have worked to build and develop our country; and | Respekteer diegene wat hul beywer het om ons land op te bou en te ontwikkel; en | Sihlonipha labo abasebenzileko ekwakhiweni nekuthuthukisweni kwephasi lekhethu; begodu | Siyabahlonela abo baye basebenzela ukwakha nokuphucula ilizwe lethu; kwaye | Sihlonipha labo abasebenzele ukwakha nokuthuthukisa izwe lethu; futhi | Sihlonipha labo labaye basebentela kwakha nekutfutfukisa live lakitsi; futsi | Re hlompha bao ba ilego ba katanela go aga le go hlabolla naga ya gaborena; mme | Re tlotla ba ileng ba sebeletsa ho aha le ho ntshetsa pele naha ya rona; mme | Re tlotla ba ba diretseng go aga le go tlhabolola naga ya rona; mme | Ri ṱhonifha havho vhe vha shuma vha tshi itela u fhaṱa na u bveledzisa shango ḽashu; na | Hi hlonipha lava tirheke ku aka no hluvukisa tiko ra hina; no |

| Believe that South Africa belongs to all who live in it, united in our diversity. | Glo dat Suid-Afrika behoort aan almal wat daarin woon, verenig in ons verskeidenheid. | Sikholwa bonyana iSewula Afrika ingeyabo boke abandzindze kiyo, sibambisane ngokwahlukahlukana kwethu. | Sikholelwa kwelokuba uMzantsi-Afrika ngowabo bonke abahlala kuwo, bemanyene nangona bengafani. | Sikholelwa ukuthi iNingizimu Afrika ingeyabo bonke abahlala kuyo, sibumbene nakuba singafani. | Sikholelwa ekutseni iNingizimu Afrika yabo bonkhe labahlala kuyo, sihlangene ngekwehlukahlukana kwetfu; | Re dumela gore Afrika-Borwa ke ya batho bohle ba ba dulago go yona, re le ngata e tee e nago le pharologano | Re dumela hore Afrika Borwa ke naha ya bohle ba phelang ho yona, re kopane le ha re fapane. | Re dumela fa Aforika Borwa e le ya botlhe ba ba tshelang mo go yona, re le ngata e le nngwe ka go farologana | U tenda uri Afrika Tshipembe ndi ḽa vhoṱhe vhane vha dzula khaḽo, vho vhofhekanywaho vha vha huthihi naho vha sa fani. | Tshembha leswaku Afrika Dzonga i ya vanhu hinkwavo lava tshamaka eka rona, hi hlanganile hi ku hambana-hambana ka hina. |

- "Africa :: SOUTH AFRICA". CIA The World Factbook. 8 March 2022.

- Alexander, Mary (6 March 2018). "The 11 languages of South Africa - South Africa Gateway". South Africa Gateway. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- The Economist, "Tongues under threat", 22 January 2011, p. 58.

- Mesthrie, Rajend; Rajend, Mesthrie (17 October 2002). Language in South Africa. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-79105-2.

- Census 2011: Census in brief (PDF). Pretoria: Statistics South Africa. 2012. pp. 23–25. ISBN 9780621413885.

- "South Africa". Ethnologue. Retrieved 4 September 2022.

- "A Comunidade dos Países de Língua Portuguesa, com Jorge Couto" [The Community of Portuguese-Speaking Countries, with Jorge Couto] (in Portuguese). Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- "Portuguese Migration to, And Settlement in South Africa: 1510-2013" (PDF). SSIIM (UNESCO Chair on the Social and Spatial Inclusion of International Migrants – Urban Policies and Practices). 10 May 2013. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- Palusci, Oriana (2010). English, But Not Quite: Locating Linguistic Diversity. p. 180. ISBN 9788864580074.

- "Constitution of the Republic of South Africa Act 200 of 1993". www.gov.za. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- "Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 - Chapter 1: Founding Provisions". www.gov.za. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- "Constitution 1996" (PDF). justice.gov.za. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- "Constitution 1998" (PDF). justice.gov.za. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- "Constitution 1996" (PDF). justice.gov.za. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- "Constitution 1996" (PDF). justice.gov.za. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- "Constitution 1996" (PDF). justice.gov.za. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- "Constitution 1996" (PDF). justice.gov.za. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- "Constitution 1996" (PDF). justice.gov.za. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- "Constitution 1996" (PDF). justice.gov.za. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- "Constitution 1996" (PDF). justice.gov.za. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- "Constitution 1996" (PDF). justice.gov.za. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- Introduction to the languages of South Africa

- Ethnologue Listing of South African Languages

- PanAfriL10n page on South Africa

- Statistics SA

- Hornberger, Nancy H. "Language Policy, Language Education, Language Rights: Indigenous, Immigrant, and International Perspectives." Language in Society, Vol. 27, No. 4 (Dec., 1998), pp. 439–458

- Alexander, Mary. The 11 languages of South Africa (January 2018)