Minor_Rock_Edicts

Minor Rock Edicts

Ancient rock inscriptions in India attributed to Mauryan emperor Ashoka

The Minor Rock Edicts of Ashoka (r. 269–233 BCE)[1] are rock inscriptions which form the earliest part of the Edicts of Ashoka, and predate Ashoka's Major Rock Edicts. These are the first edicts in the Indian language of Emperor Ashoka, written in the Brahmi script in the 11th year of his reign. They follow chronologically the Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription, in Greek and in Aramaic, written in the 10th year of his reign (260 BCE),[2][3] which is the first known inscription of Ashoka.[4]

| Minor Rock Edicts of Ashoka | |

|---|---|

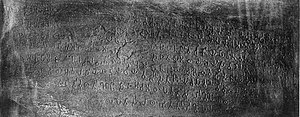

Minor rock edict of Sasaram. | |

| Material | Rock, stone |

| Created | 3rd century BCE |

| Discovered | 1893 |

| Present location | India |

There are several slight variations in the content of these edicts, depending on location, but a common designation is usually used, with Minor Rock Edict N°1 (MRE1)[5] and a Minor Rock Edict N°2 (MRE2), which does not appear alone but always in combination with Edict N°1), the different versions being generally aggregated in most translations. There is also a minor edict No.3, discovered in Bairat, for the Buddhist clergy.[6]

The inscriptions of Ashoka in Greek or Aramaic are sometimes also categorized as "Minor Rock Edicts".

The Minor Pillar Edicts of Ashoka refer to five separate Edicts inscribed on columns, the Pillars of Ashoka. These edicts are preceded chronologically by the Minor Rock Edicts and may have been made in parallel with the Major Rock Edicts.

The Minor Rock Edicts were written quite early in the reign of Ashoka, from the 11th year of his reign at the earliest (according to his own inscription, "two and a half years after becoming a secular Buddhist", i.e. two and a half years at least after the Kalinga conquest of the eighth year of his reign, which is the starting point for his gradual conversion to Buddhism). The technical quality of the engraving of the inscriptions is generally very poor, and generally very inferior to the pillar edicts dated to the years 26 and 27 of Ashoka's reign.[7]

The Minor Rock Edicts therefore follow the very first inscription of Ashoka, written in year 10 of his reign, the Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription established at Chilzina, Kandahar, in the center of Afghanistan.[8] This first inscription was written in Classical Greek and Aramaic exclusively.

The Minor Rock Edicts maybe slightly earlier than the Major Rock Edicts established to propagate the Dharma, from the 12th year of Ashoka's reign.[9] These Ashoka inscriptions are in Indian languages with the exception of the Kandahar Greek Edict of Ashoka inscribed on a limestone stele.[8] It was only later, during the 26th and 27th years of his reign, that Ashoka wrote new edicts, this time on majestic columns, the pillars of Ashoka.[9][7]

The different variations of edicts on rock 1 and 2 are usually presented in the form of a compilation.[10] There is also a minor edict on Rock No.3, discovered in Bairat only, addressing not the Ashoka officers as the first two edicts, but the Buddhist clergy, with the recommendation to study a very specific list of Buddhist scriptures.[11]

In the Minor Rock Edicts, Ashoka makes explicit mention of his religious affiliation by presenting himself as a "lay disciple" or "disciple of the Buddha" according to the versions, and speaking of his proximity to "the order" (samgha), which is far from the case in most other edicts where he is only promulgating the moral laws of "Dharma".

- Association of Ashoka with the title "Devanampriya" ("Beloved-of-the-Gods")

There are slight variations between each of the versions of the Minor Rock Edicts. The Maski version of Minor Rock Edict No.1 was historically especially important in that it confirmed the association of the honorific title "Devanampriya" with Ashoka:[12][13]

[A proclamation] of Devanampriya Asoka.

Two and a half years [and somewhat more] (have passed) since I am a Buddha-Sakya.

[A year and] somewhat more (has passed) [since] I have visited the Samgha and have shown zeal.

Those gods who formerly had been unmingled (with men) in Jambudvipa, have how become mingled (with them).

This object can be reached even by a lowly (person) who is devoted to morality.

One must not think thus, — (viz.) that only an exalted (person) may reach this.

Both the lowly and the exalted must be told : "If you act thus, this matter (will be) prosperous and of long duration, and will thus progress to one and a half.

In the Gujarra Minor Rock Edict also, the name of Ashoka is used together with his titles: "Devanampiya Piyadasi Asokaraja".[15]

- Pre-existence of pillars

In the Minor Rock Edicts, Ashoka also mentions the duty to inscribe his edicts on the rocks and on the pillars ("wherever there is a pillar or rock"). This has led some authors, especially John Irwin, to think that there were already pillars in India before Ashoka erected them. For John Irwin, examples today of these pillars prior to Ashoka would be the bull pillar of Rampurva, the elephant pillar of Sankissa, and the Allahabad pillar of Ashoka.[16] None of these pillars received the inscription of the Minor Rock Edicts, and only the pillar of Allahabad has inscriptions of Ashoka, which weakens this theory, since, according to the orders of the same of Ashoka, they should have been engraved with his Minor Rock Edicts.

- Language of the edicts

Several edicts of Ashoka are known in Greek and Aramaic; by contrast the many minor edicts on rock engraved in southern India in Karnataka use the Prakrit of the North as the language of communication, with the Brahmi script, and not the local Dravidian idiom, which can be interpreted as a kind of intrusion and authoritarianism in respect to the southern territories.[17]

Full texts of the Minor Rock Edicts

- Minor Rock Edict No.1

In this Edict, Ashoka describes himself as a Buddhist layman (Upāsaka)[18] /a Buddha-Śaka[19] /a Saka,[20] and also explains he has been getting closer to the Sangha and has become more ardent in the faith.

| English translation | Prakrit in Brahmi script |

|---|---|

|

- Minor Rock Edict No.2

Only appears in a few places, in conjunction with Minor Edict No.1

| English translation | Prakrit in Brahmi script |

|---|---|

|

- Minor Rock Edict No.3

Only appears at Bairat, where it was discovered in front of the Bairat Temple, possibly the oldest free-standing temple in India. The Edict is now located in the Museum of The Asiatic Society, Calcutta, and because of this is sometimes called the "Calcutta-Bairāṭ inscription".[22][23] Also known as the Bhabru Edict.[24] Ashoka claims "great is my reverence and faith in the Buddha, the Dharma (and) the Samgha", and makes a list of recommended Buddhist scriptures that Buddhist monks as well as the laity should repeatedly study.

| English translation | Prakrit in Brahmi script |

|---|---|

|

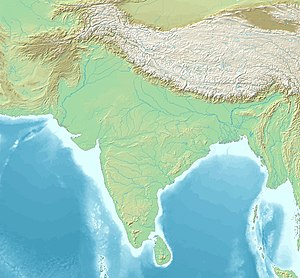

The minor rock edicts of Ashoka are exclusively inscribed on rock. They are located throughout the Indian subcontinent. Edict N°1 appears alone in Panguraria, Maski, Palkigundu et Gavimath, Bahapur/Srinivaspuri, Bairat, Ahraura, Gujarra, Sasaram, Rajula Mandagiri, Rupnath, Ratampurwa and in conjunction with Edict N°2 at Yerragudi, Udegolam, Nittur, Brahmagiri, Siddapur, Jatinga-Rameshwara.[25]

The traditional Minor Rock Edicts (excluding the miscellaneous inscriptions in Aramaic or Greek found in Pakistan and Afghanistan) are located in central and southern India, whereas the Major Rock Edicts were located at the frontiers on Ashoka's territory.[26]

| Name | Location | Map | Overview | Rock | Rubbing / Close-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bahapur | Location of Srinivaspuri near Kalkaji Temple, in the Kailash Colony, near the Bahapur area, South Delhi Minor rock edict # 1 only.[25] 28.55856°N 77.25662°E / 28.55856; 77.25662 Local 3D view |  | |||

| Gujarra | Near Jhansi, Datia district, Madhya Pradesh. Minor rock edict # 1 only.[25] Here, the name of Ashoka is used together with his titles: "Devanampiya Piyadasi Asokaraja".[15][27]Full inscription 25.57699°N 78.54594°E / 25.57699; 78.54594 The authenticity of this inscription has been doubted.[28] |

||||

| Saru Maru/ Panguraria | Sehore District, Madhya Pradesh. Minor rock edict # 1 only[25][30] 22.729949°N 77.519910°E / 22.729949; 77.519910 In Saru Maru/Panguraria there is also a commemorative inscription referring to the visit of Ashoka as a young man, while he was still viceroy of Madhya Pradesh:[31][32]

|

||||

| Udegolam | Bellary District, Karnataka. Minor rock edict n°1 and n°2[25] 15.52000°N 76.83361°E / 15.52000; 76.83361 | ||||

| Nittur | Bellary District, Karnataka. Minor rock edicts #1 and #2[25] 15.54717°N 76.83270°E / 15.54717; 76.83270 | ||||

| Maski | Maski, Raichur district, Karnataka. Minor rock edict #1 only[25] "[A proclamation] of Devanampriya Asoka." "Two and a half year [and somewhat more] (have passed) since I am a Buddha-Sakya..." Full inscription 15.95723°N 76.64122°E / 15.95723; 76.64122 |

||||

| Siddapur | Near Brahmagiri, Karnataka (14°48'49" N 76°47'58" E). Minor rock edicts # 1 and #2[25] Full inscription 14.81361°N 76.79944°E / 14.81361; 76.79944 | ||||

| Brahmagiri | Chitradurga district, Karnataka. Minor rock edicts n°1 and n°2[25] Full inscription 14.81361°N 76.80611°E / 14.81361; 76.80611 | . | |||

| Jatinga-Rameshwara | Near Brahmagiri, Karnataka. Minor rock edicts n°1 and n°2[25] Full inscription 14.84972°N 76.79083°E / 14.84972; 76.79083 | . | |||

| Palkigundu and Gavimath | Main article: Palkigundu and Gavimath, Koppal Palkigundu and Gavimath (also called "Gavi Matha Koppal"), Koppal district, Karnataka. Minor roc edict #1 only[25] 15.34416°N 76.13694°E / 15.34416; 76.13694 15.33729°N 76.16213°E / 15.33729; 76.16213 | ||||

| Rajula Mandagiri | Near Pattikonda, Kurnool district, Andhra Pradesh. Minor rock edict #1 only[25] 15.43500°N 77.47166°E / 15.43500; 77.47166 | ||||

| Yerragudi | Gooty, near Guntakal, Anantapur, Andhra Pradesh. Minor rock edicts n°1 and n°2.[25] The Major Rock Edicts are also present here.[33] 15.20995°N 77.57688°E / 15.20995; 77.57688 | ||||

| Sasaram / Sahasram | Rohtas District, Bihar. The edict is located near the top of the terminal spur of the Kimur Range near Sasaram.[34] Minor rock edict #1 only[25] "...And where there are stone pillars here in my dominion, there also cause it to be engraved." Full inscription 24.94138°N 84.03833°E / 24.94138; 84.03833 | ||||

| Rupnath | On Kaimur Hills near Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh; ASI page "Two and a half years [and somewhat more] (have passed) since I am openly a Sakya..." Full inscription 23.64083°N 80.03194°E / 23.64083; 80.03194 | Image | |||

| Bairat | Found on a very large rock, on the hill north of Bairat, Rajasthan. Minor rock edict #1 only[25] Full inscription 27.45188°N 76.18499°E / 27.45188; 76.18499 | ||||

| Calcutta/Bairat | An inscription found on the hill about one mile southwest of Bairat, Rajasthan, on a block of granite on the platform between the Bairat Temple and the large cannon-shaped rock in front of it.[37][38] The edict was discovered by Captain Burt in 1840,[38] and transferred to the Museum of the Asiatic Society of Bengal at Calcutta, hence the name "Calcutta-Bairat", also called the Bhabra or Bhabru Edict.[39] Contains Minor rock edict #3 only, in which Ashoka gives a list of Buddhist scriptures to study.[25] "...It is known to you Sirs, how great is my faith and reverence in the Buddha, the Dharma and the Sangha..." Full inscription In this inscription, Ashoka is referred to as "Piyadasi Raja Magadhe" ("Piyadasi, king of Magadha").[40] 27.417124°N 76.162569°E / 27.417124; 76.162569 |

Modern image in the Asiatic Society | |||

| Ahraura | Mirzapur District, Uttar Pradesh. Minor rock edict #1 only[25] · [41] 25.02000°N 83.02000°E / 25.02000; 83.02000 | Image | |||

| Ratampurwa | Kaimur District, Bihar. Identical to the Sasaram rock edict.[42] 25.018067°N 83.341657°E / 25.018067; 83.341657 | Images | |||

Some Ashoka inscriptions in Greek or Aramaic, or the inscriptions of the Barabar Caves, are difficult to categorize, and are sometimes included in the "Minor Rock Edicts".

This is sometimes also the case with the Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription (the designation of "Minor Rock Edict No.4" was proposed), although its nature is quite different from other edicts and it is the oldest of Ashoka's inscriptions (10th year of his reign).[43]

The inscriptions in Aramaic, especially the Aramaic Inscription of Laghman and the Aramaic Inscription of Taxila are also often catalogued among the minor rock edicts, although their character of edict is not very clear, and if the first was inscribed on rock, the second was inscribed on an octagonal marble pillar.

The inscriptions of the Barabar Caves are purely dedicatory, without moral content.

| Name | Location | Map | Overview | Rock | Rubbing/ Close-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription | Chil-Zena Hill, Kandahar, Afghanistan Original bilingual Greek-Aramaic edition, sort of a summary or introduction of the Edicts of Ashoka. Sometimes categorized as "Minor Rock Edict No. 4", due to its more recent discovery, although it is the oldest of all Ashoka inscriptions (year 10 of his reign). Two Major Rock Edicts, the Kandahar Greek Edict of Ashoka, were also discovered in Kandahar. | ||||

| Aramaic Inscription of Laghman | Valley of Laghman, Afghanistan Short moral injunction accompanied by information for the journey to Palmyra. | ||||

| Aramaic Inscription of Taxila | Greek city of Sirkap, Taxila, Pakistan. Not perfectly identified inscription, engraved on a marble architectural block, mentioning "Our Lord Priyadasi" (Ashoka) twice . |  | |||

| Inscriptions of Ashoka (caves of Barabar) | Barabar Caves, Bihar |

- Le Huu Phuoc, Buddhist Architecture. Grafikol 2009. ISBN 978-0-9844043-0-8.

- Valeri P. Yailenko Les maximes delphiques d'Aï Khanoum et la formation de la doctrine du dharma d'Asoka. Dialogues d'histoire ancienne vol.16 n°1, 1990, pp. 239–256.

- Phuoc 2009, p.30

- Valeri P. Yailenko Les maximes delphiques d'Aï Khanoum et la formation de la doctrine du dharma d'Asoka Dialogues d'histoire ancienne vol.16 n°1, 1990, p.243

- Minor Rock Edict 1

- John Irwin, "The True Chronology of Aśokan Pillars", in:Artibus Asiae, Vol. 44, No. 4 (1983), p. 247-265

- Valeri P. Yailenko Les maximes delphiques d'Aï Khanoum et la formation de la doctrine du dharma d'Asoka Dialogues d'histoire ancienne vol.16 n°1, 1990, pp.239-256

- A translation of the Edicts of Ashoka p.259 Archived 2017-05-17 at the Wayback Machine

- The Cambridge Shorter History of India. CUP Archive. p. 42.

- Gupta, Subhadra Sen (2009). Ashoka. Penguin UK. p. 13. ISBN 9788184758078.

- Inscriptions of Asoka. New Edition by E. Hultzsch (in Sanskrit). 1925. pp. 174–175.

- Malalasekera, Gunapala Piyasena (1990). Encyclopaedia of Buddhism. Government of Ceylon. p. 16.

- The term Upasaka (Buddhist layman) is used in most inscriptions.Inscriptions of Asoka. New Edition by E. Hultzsch (in Sanskrit). 1925. p. 167 Note 18.

- Maski inscription Inscriptions of Asoka. New Edition by E. Hultzsch (in Sanskrit). 1925. p. 174.

- Rupnath inscription Inscriptions of Asoka. New Edition by E. Hultzsch (in Sanskrit). 1925. p. 167.

- The term Upāsaka (Buddhist layman) is used in most inscriptions.Inscriptions of Asoka. New Edition by E. Hultzsch (in Sanskrit). 1925. p. 167 Note 18.

- "History of Museum Asiatic Society". www.asiaticsocietykolkata.org.

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (2017). Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia. Princeton University Press. p. 245. ISBN 978-0-691-17632-1.

- Singh, Upinder (2017). Political Violence in Ancient India. Harvard University Press. p. 501. ISBN 9780674975279.

- Hirakawa, Akira (1993). A History of Indian Buddhism: From Śākyamuni to Early Mahāyāna. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 96. ISBN 9788120809550.

- Sircar, D. C. (1979). Asokan studies. pp. 86–96.

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (2017). Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia. Princeton University Press. pp. 239–240, note 47. ISBN 978-0-691-17632-1.

- Sircar, D. C. (1979). Asokan studies.

- Sircar, D. C. (1979). Asokan studies. p. Plate XVII.

- Gupta, The Origins of Indian Art, p.196

- Allen, Charles (2012). Ashoka: The Search for India's Lost Emperor. Little, Brown Book Group. pp. 154–155. ISBN 9781408703885.

- Inscriptions of Asoka. New Edition by E. Hultzsch (in Sanskrit). 1925. pp. 169–171.

- Lahiri, Nayanjot (2015). Ashoka in Ancient India. Harvard University Press. p. 37. ISBN 9780674057777.

- Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. Calcutta : Printed at the Baptist Mission Press [etc.] 1840. p. 616.

- Sastri, Kallidaikurichi Aiyah Nilakanta (1988). Age of the Nandas and Mauryas. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 208. ISBN 9788120804661.

- Falk, Harry. The Minor Rock Edict of Asoka at Ratanpurwa.