Mountain_War

Mountain War (Lebanon)

Part of the Lebanese Civil War

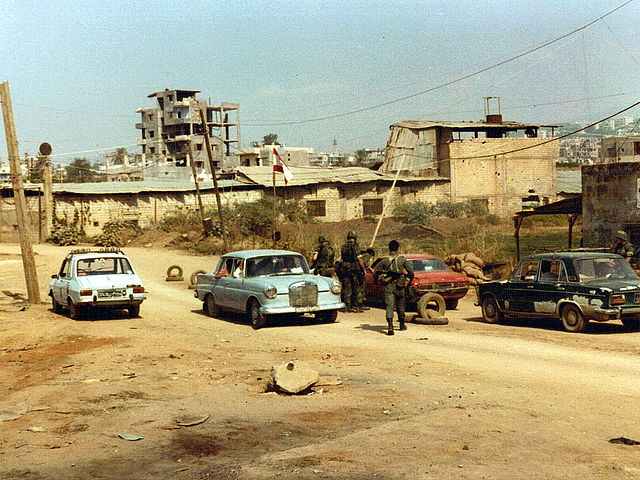

The Mountain War (Arabic: حرب الجبل | Harb al-Jabal), also known as the War of the Mountain, was a subconflict between the 1982–83 phase of the Lebanese Civil War and the 1984–89 phase of the Lebanese Civil War, which occurred at the mountainous Chouf District located south-east of the Lebanese Capital Beirut. It pitted the Christian Lebanese Forces militia (LF) and the official Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF) against a coalition of the Druze Progressive Socialist Party (PSP) and the PNSF's Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine – General Command (PFLP-GC), Fatah al-Intifada and As-Sa'iqa backed by Syria. Hostilities began when the LF and the LAF entered the predominantly Druze Chouf district to bring back the region under government control, only to be met with fierce resistance from local Druze militias and their allies. The PSP leader Walid Jumblatt's persistence to join the central government and his instigation of a wider opposition faction led to disintegration of the already fragile LAF and the eventual collapse of the government under President Amin Gemayel.

| Mountain War حرب الجبل | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Lebanese Civil War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Abu Musa |

| ||||||

In the wake of the June 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon, the main Maronite Christian ally of Israel, the Lebanese Forces (LF) militia of the Kataeb Party commanded by Bashir Gemayel sought to expand its area of influence in Lebanon. The LF tried to take advantage of Israel Defense Forces (IDF) advances to begin deploying troops in areas where they had not been present before. This territorial expansion policy was focused on regions known to harbor a large Christian rural population, such as the mountainous Chouf District, located south-east of Beirut. Following the assassination of their leader – and President-elected of Lebanon – Bashir Gemayel in September 1982, the LF command council decided late that month to enter the Chouf. The head of LF intelligence, Elie Hobeika, voiced his opposition to the entry, but was overruled by his fellow senior commanders of the council, Fadi Frem and Fouad Abou Nader. With the tacit backing of the IDF, Lebanese Forces' units under the command of Samir Geagea (appointed Commander of all LF forces in the Chouf-Aley sector of Mount Lebanon in January 1983) moved into the Christian-populated areas of the western Chouf. By early 1983, the Lebanese Forces' managed to establish garrisons at a number of key towns in the Chouf, namely Aley, Deir el-Qamar, Souk El Gharb, Kfarmatta, Bhamdoun, Kabr Chmoun and others.[1] However, this brought them into confrontation with the local Druze community, who viewed the LF as intruders on their territory.

Historically the relationship between the Druze and Maronite Christians in the Chouf Mountains has been characterized by harmony and peaceful coexistence,[2][3][4][5] with amicable relations between the two groups prevailing throughout history, with the exception of some periods, including the 1860 Mount Lebanon civil war. The Maronites and the Druze were long-standing enemies since the 1860s – when a bloody civil war tore apart the Mount Lebanon Emirate, on which thousands of Christians were massacred by the Druzes – and old enmities were rearoused when Geagea's Maronite troops tried to pay old historic debts by imposing their authority on the Chouf by force. Some 145 Druze civilians were reportedly killed by the Lebanese Forces at Kfarmatta (although other sources allege that the death toll mounted to 200 people),[6][7] followed by other killings at Sayed Abdullah, Salimeh and Ras el-Matn in the Baabda District, and sporadic fighting soon broke out between the LF and the main Druze militia, the People's Liberation Army (PLA) of the Progressive Socialist Party (PSP).

Re-organization of the LAF

The new Lebanese President Amin Gemayel – brother of the late Bashir, elected as his successor on 21 September – requested that a second U.S., French and Italian (soon joined by a small British contingent) peacekeeping Multinational Force (MNF II) be deployed in and around the Greater Beirut area to maintain order, although the political objectives of this deployment were not clearly defined.[8] President Amin Gemayel and Lieutenant general Ibrahim Tannous, the newly appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Lebanese Armed Forces (LAF), also succeeded in persuading the United States Government to assist Lebanon in rebuilding its depleted army.[9][10] As early as October 1978,[11] plans were drawn to create a system of light mechanized infantry brigades, and although the nuclei of eight brigades, plus a Headquarters' Brigade and a Republican Guard Brigade had been created by mid-1982, most were well below strength.[12] Under the auspices of the U.S.-funded Lebanese Army Modernization Program (LAMP), the Lebanese Government proceeded to re-organize the LAF brigades – combined with the manpower provided by conscription, which allowed their rapid expansion – with material help from Jordan, the United States and France, whose MNF contingents (U.S. Marines and French Foreign Legion Paratroopers) began training Lebanese soldiers, followed by the end of the year of the arrival of arms shipments.[10] This stance however, eroded the neutrality of the MNF at the eyes of the Lebanese Muslims, since they did not perceive the LAF as a true national defense force that would protect the interests of all factions.[13] Indeed, the LAF was almost wholly controlled by the Christians.[14]

The Lebanese Army re-enters west Beirut

Between 2 and 15 October 1982, the newly-raised 6th Defence Brigade under the command of Colonel Michel Aoun re-entered west Beirut alongside other Lebanese Army units and the Internal Security Forces (ISF), ostensibly to carry out the pacification of the Muslim-populated districts of the Capital city. Acting in collusion with the Lebanese Forces, they arrested 1,441 Muslims (other sources indicate a higher number, some 2,000) who were either members or supporters of Leftist political groups and subsequently disappeared; none was heard of again.[15][16][17]

After the Lebanese Army regained control of west Beirut,[18] Lt. Gen. Tannous turned his attention to the Chouf District and on 18 October, his troops began to reassert their presence in the region. However, they were unable to stop the ongoing Christian-Druze clashes, mostly due to Israeli presence in the area, which tended to restrict Lebanese government' forces activity.[19]

In November, fighting in the Chouf spread into the south-western suburbs of Beirut and friction in the Lebanese Capital increased after 1 December, when the Druze PSP leader Walid Jumblatt was injured in an assassination attempt by a car-bomb explosion outside his residence.[20] On 20 December fighting broke out again between the Christian LF and the Druze PSP/PLA militias at the town of Aley which rumbled on until 7 February 1983, when the Druze overrun the town and drove out the Christian garrison.[21]

On 18 April a suicide bomber drove a delivery van packed with explosives into the lobby of the U.S. Embassy at west Beirut, killing 63 people – among the dead were Robert Ames, a senior Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) analyst, and six personnel from the CIA station in Lebanon. Responsibility was claimed by the hitherto unknown Islamic Jihad Organization (IJO), a Lebanese Shi'ite militia supported by Iran and based near Baalbek in the Syrian-controlled Beqaa Valley. This attack inaugurated the saga of suicide car- and truck-bombings in Lebanon.[22][23]

On 28 April, the fighting between Christian LF and Druze PSP/PLA militias resumed in the Chouf and in the northern part of the Matn District, spilling over into the southern suburbs of east Beirut, which were bombarded by Druze artillery batteries positioned at Dhour El Choueir, Arbaniyeh, Salimeh and Maaroufiyeh in the Baabda District. Fighting in the Chouf spilled over again into Beirut, this time in the form of further artillery shelling by the Druze PLA between 5 and 8 May.

17 May Agreement

After six months of prolonged U.S.-mediated secret negotiations, representatives of the Lebanese, Israeli, and American governments signed a withdrawal agreement on 17 May 1983, which became known as the 'May 17 Agreement', that provided for the evacuation of all foreign armed forces from Lebanon. However, implementation of the Withdrawal Agreement depended entirely upon the cooperation of Syria who, incensed for being neither invited to the negotiations nor consulted prior to the signature of the agreement, rejected it by refusing to withdraw its 30,000 troops stationed in Lebanon. Many Lebanese, both Christian and Muslim, were not in favour of a U.S.-sponsored agreement either, which included severe security terms imposed by the Israelis and practically treated Lebanon as a defeated country. Although the agreement was approved by the Lebanese Parliament, President Amin Gemayel refused to ratify it, a decision that irritated the Israeli Prime-Minister Menahem Begin.[24] Lebanese Sunni and Shia Muslims also felt both threatened and marginalized when their President, confident of U.S. political and military support, avoided implementing the much-needed political reforms to which the mainly Muslim Political Parties and militias felt entitled.[8]

Increasing tensions

As a result, internal political and armed opposition to the weak Gemayel administration grew intensively throughout the country. On 22 May, a number of clashes occurred in the Chouf Mountains, as the Druze PSP/PLA militia moved to expel the Lebanese Forces from their remaining positions in the area. Despite the heavy presence of IDF units in the region, the Israelis had little interest at getting involved in the Lebanese inter-sectarian strife, and made no attempt to intervene in the behalf of their LF allies.

During the summer of 1983 the situation in Lebanon degenerated into a vicious power struggle between Lebanese rival factions, with the MNF caught in the middle. Both the Israelis and Syrians withdrew to more defensive positions and tried to outmaneuver each other by playing their local proxies, with mixed results. Seemingly oblivious to the deteriorating political and military situation, the U.S. government did nothing to demonstrate its neutrality. In June, rather than cancelling or descaling the training and arming of the LAF ground forces, the U.S. Marines began joint patrols with them,[15] whilst the French, Italian and British contingents of the Multinational Force refrained from doing so, fearing that such a partisan move would compromise the neutrality of the MNF.

At the same time, the Lebanese central government was planning to re-impose its authority over the Chouf District, and on 9–10 July, LAF troops occupied an observation post recently abandoned by the IDF, located on the hills to the east of Beirut. President Gemayel and Lt. Gen. Tannous wanted to step up full deployment of combat units of the reformed Lebanese Armed Forces to the area, to act as a buffer between the LF and the PSP. This was objected by the Druze leader Walid Jumblatt, who accused the LAF of primarily serving the Kataeb interests, and began to re-organize and re-arm his PLA militia with Syrian material help. As relations between Lebanese President Gemayel and Israeli Defense Minister Ariel Sharon deteriorated, the IDF was accused of turning a blind eye to the Druze military build-up in the Chouf by doing nothing to impede Syrian arms shipments' convoys bound for the Druze militias from passing through their checkpoints in the region.[25]

Clashes with the Druze in the Chouf

The first engagement between the Druze PSP/PLA and the LAF occurred on 14 July, when a Lebanese Army unit accompanying an IDF patrol was ambushed by Druze guerrillas. Fourteen Lebanese soldiers and two Druze militiamen were killed in the attack, and in response the artillery units of Jumblatt's PLA shelled on 18th, 20th, 22nd and 23rd the Christian-held neighborhoods of east Beirut (in which over 30 people were killed and 600 injured, mostly civilians) and U.S. Marines positions at Beirut International Airport in Khalde, wounding three Marines.[15] In between, the Lebanese Army engaged for the first time between 15 and 17 July the Shia Amal militia in West Beirut over a dispute involving the eviction of Shi'ite squatters from a schoolhouse.

On 23 July, Jumblatt announced the formation of a Syrian-backed coalition, the Lebanese National Salvation Front (LNSF) that rallied several Lebanese Muslim and Christian parties and militias opposed to 17 May Agreement, and fighting between the Druze PLA and LF and between the Druze and LAF, intensified during the month of August. Intense Druze PLA artillery shelling forced the Beirut International Airport to close between 10 and 16 August, and the Druze PSP/PLA leadership made explicit their opposition to the deployment of LAF units in the Chouf.[26] The U.S. Marines compound came under further Druze PLA shell-fire on 28 August, this time killing two Marines, which led the Marines to retaliate with their own artillery, shelling the Druze positions in the Chouf with 155mm high-explosive rounds. This incident marked the beginning of the shooting war for the U.S. military forces in Lebanon.[15] Although President Gemayel accused Syria of being behind the Druze shelling and threatened to respond accordingly, artillery duels between the LAF and Druze militias continued sporadically until a ceasefire came in effect on late August.

Clashes with Amal in Beirut

As these events were unfolding in the Chouf, tensions continued to mount at Muslim-populated west Beirut. They finally exploded in mid-August when a general strike called on the 15th quickly escalated into open warfare, which pitted the Shia Amal militia led by Nabih Berri against the Lebanese Armed Forces. Although Amal had managed to seize control of much of west Beirut after two weeks of street-fighting, hostilities resumed on 28 August near MNF positions in the southern edge of Beirut which caused several casualties. Response was not long in coming, and two days later, LAF troops assisted by MNF detachments backed by artillery and U.S. Marines' Bell AH-1 Cobra attack helicopters, made successful counterattacks and regained control of the Muslim quarters.[27]

The Israelis withdraw from the Chouf

No longer able to sustain the casualties that the IDF was taking in policing the Chouf District, and increasingly despairing of President Gemayel's ability to work out an understanding with his mounting Druze and Muslim Shia opposition, the Israelis decided on 31 August to withdraw unilaterally from the region and the area around Beirut to new positions further south along the Awali River, ostensibly to allow the Lebanese Army to resume control over the area.[28][22] This unexpected move effectively removed the buffer made by the IDF between the Druze and Christian militias, which now maneuvered toward an inevitable confrontation.[29] Some international analysts have argued that the Israelis had deliberately provoked the conflict so that their Christian LF allies could establish themselves in the area.[30] New recordings of a phone call between the U.S. President Ronald Reagan and the Israeli prime minister Menachem Begin released by the New York Post in November 2014 revealed a request made by Reagan to the Israeli Prime-minister to delay the withdrawal of Israeli troops from the Chouf mountains.[31] In any event, the cease-fire in the Chouf barely held for a week, and triggered another round of brutal fighting which caused Walid Jumblatt to declare on 1 September that the Druze community of Lebanon was now formally at war with the Christian-dominated Gemayel government in east Beirut. The "Mountain War" had begun.

September 1983

On 3 September, the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) commenced the first part of a phased withdrawal plan codenamed Operation Millstone, by quickly pulling out its troops from their positions on the southern edge of Beirut and from a section of the Beirut-Aley-Damascus Highway, and within twenty-four hours Israeli units had completed its redeployment south of the Awali River line. Surprised by this unexpected Israeli move, the largely unprepared Lebanese Armed Forces brigades (still being trained by the United States) then rushed south to occupy Khalde and the road adjacent to Beirut International Airport, but ran into difficulties near Aley, where heavy fighting between the Druze and LF militias persisted.[32]

Opposing forces

At this point, Jumblatt's 17,000-strong PSP/PLA militia was now part of a military coalition under the LNSF banner that gathered 300 Druze fighters sent by its Druze rival Majid Arslan and head of the powerful Yazbaki clan, 2,000 Syrian Social Nationalist Party (SSNP) militiamen under Inaam Raad, 3,000 Nasserite fighters of the Al-Mourabitoun led by the Sunni Muslim Ibrahim Kulaylat and some 5,000 Popular Guards' militiamen of the Lebanese Communist Party (LCP) under Elias Atallah. In addition, the Shia Amal militia (not part of the alliance) at West Beirut was later able to mobilize 10,000 fighters. Their Palestinian allies of the LNSF included the PFLP-GC led by Ahmed Jibril and the Fatah al-Intifada led by Colonel Said al-Muragha (a.k.a. 'Abu Musa'), who fielded a few thousand hardened fighters. Both Amal and the PSP-led LNSF coalition received the discreet, yet fundamental backing of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and the Syrian Army, who provided crucial logistical and artillery support.

The Lebanese Forces militia had about 2,500 lightly equipped Christian militiamen in the Chouf, mostly tied up in static garrison duties throughout the region's main towns whereas another 2,000 fighters were deployed alongside LAF ground units at west Beirut. The Lebanese Army committed nine newly formed mechanized infantry brigades – the Third Brigade, Fourth Brigade, Fifth Brigade, Sixth Brigade, Seventh Brigade, Eighth Brigade, Ninth Brigade, Tenth Brigade and the Eleventh Brigade – totaling roughly some 30,000 men, placed under the overall command of Lt. Gen. Tannous and the Lebanese Armed Forces Chief-of-Staff, the Druze General Nadim al-Hakim.[33] Deployed in the western Chouf, and at both the western and eastern sectors of Beirut, the army brigades benefited from aerial, artillery, and logistical support lent by U.S. and French forces of the MNF contingent. In this post-Israeli period in the Chouf, the Lebanese Forces and the regular army occasionally fought side-by-side, but at other times were opponents. This lack of coordination between the LF and the government was due to the deep distrust that LF senior commanders felt towards President Amine Gemayel, its moderate political posture and relations with Lebanese Muslim and Palestinian leaders.[34][35]

The Druze offensive

As soon as the last Israeli units left the Chouf, the Druze launched on 5 September a full-scale offensive on Lebanese Forces' and Lebanese Army positions at Deir el-Qamar, Kabr Chmoun and Bhamdoun. A garrison of just 250 Lebanese Forces' fighters commanded by Paul Andari, the LF Deputy Field Commander of the Mountain District,[36] were defending Bhamdoun, with orders to hold their positions for 12 hours until being replaced by Lebanese Army units. However, 72 hours later the expected reinforcements failed to arrive, and it became clear that the LF counter-offensive in the coastal town of Kfarmatta aimed at opening the road to Bhamdoun had stalled.[37] Warned at the last minute by the PLO of the eminent Druze offensive, Samir Geagea, the LF supreme commander in the Mountain region, issued a general evacuation order of all Christian civilians from the towns and villages of the Aley and Chouf districts towards the symbolic town of Deir el-Qamar, site of the Christian population massacres in 1860.[37]

For their part, the LF garrison forces were completely caught by surprise by the ferocity of the assault and were outnumbered. Supported by obsolescent 25-pounder field guns,[38] ZiS-3 76.2mm anti-tank guns mounted on GAZ-66 trucks,[39] four French DEFA D921/GT-2 90mm anti-tank guns mounted on M3/M9 half tracks,[40] TOW and MILAN Jeeps,[41] Gun trucks and technicals armed with Heavy machine guns (HMGs) and recoilless rifles, and anti-aircraft autocannons mounted on wheeled BTR-152 armored personnel carriers (APCs),[42] plus two armored companies provided with Israeli-supplied Tiran 4 and captured T-54/55 Tanks,[43] backed by mechanized infantry on M3/M9 Zahlam half-tracks and M113 armored personnel carriers, they tried desperately to hold their ground at Bhamdoun against a determined enemy now equipped with four Soviet-made T-55A tanks,[44] wheeled BTR-152V1 APCs,[45][46] technicals armed with HMGs and recoilless rifles, Gun trucks equipped with AA autocannons,[47] heavy mortars,[48][49] ZiS-2 57mm anti-tank guns,[50][51] long-range artillery,[52] and MBRLs[53][54] supplied on loan by the PLO and Syria.

Bhamdoun fell on the 7th, followed two days later by Kabr Chmoun, forcing the Lebanese Forces troops' to fall back to Deir el-Qamar, which held 10,000 Christian residents and refugees and was defended by 1,000 LF militiamen;[37] the two LF armored companies managed to hold their ground at Souk El Gharb and Shahhar, and later spearheaded LF counterattacks at nearby Druze-held towns.[55] The Lebanese Forces Command in east Beirut later accused the Druze PSP of both ransacking Bhamdoun and of committing "unprecedented massacres" in the Chouf; in order to deny support, cover or a visible community for the LF to protect, the Druze implemented a 'territorial cleansing' policy to drain the Christian population from the region.[56][32] It is estimated that between 31 August and 13 September, Jumblatt's PLA militia forces overran thirty-two villages killing 1,500 people and drove another 50,000 out of their homes in the mountainous areas east and west of Beirut.[57][37][58] In retaliation, some 127 Druze civilians were killed by LF militiamen between 5–7 September at the Shahhar region, Kfarmatta, Al-Bennay, Ain Ksour, and Abey, where the LF also desecrated the tomb of a prominent Druze religious man. It is estimated that these 'tit-for-tat' killings ultimately led to the displacement of 20,000 Druze and 163,670 Christian villagers from the Chouf.[59][60]

When the Lebanese Army was forced to pull back on 12 September, in order to strengthen their position around Souk El Gharb, the Druze moved forward to fill the gap. This allowed their artillery point-blank line of sight to the U.S. Marines position at Beirut International Airport, overlooked by mountains of strategic value on three sides – designated the 'three 8' hills or Hill 888 – and on 15 September, Druze forces and their allies massed on the threshold of Souk El Gharb, a mountain resort town that controlled a ridge to the south-east of Beirut overlooking the Presidential Palace at Baabda and the Lebanese Ministry of Defense complex at Yarze.[61]

The Battle of Souk El Gharb

At Souk El Gharb and Shahhar however, the Lebanese Army was able to relieve the LF garrison units who had repulsed the first wave of Druze PLA ground assaults and were running out of supplies. For the next three days the army's Eighth Brigade led by Colonel Michel Aoun bore the brunt of the attacks, fighting desperately to retain control of Souk El Gharb, Kaifun and Bsous,[62] while the Fourth Brigade held on at Shahhar, Kabr Chmoun and Aramoun, and the 72nd Infantry Battalion from the Seventh Brigade held Dahr al-Wahsh facing Aley. The revived Lebanese Air Force (FAL in the French acronym) was also thrown into the fray for the first time since the 1975-77 phase of the Lebanese Civil War, in the form of a squadron of ten refurbished British-made Hawker Hunter fighter jets sent to support the beleaguered Lebanese Army units in the Chouf. Since their main air base at Rayak had been shelled by the Syrian Army, the Hunters had to operate from an improvised airfield at Halat, near Byblos, built by the Americans by using part of the coastal highway.

The first two combat sorties of the Lebanese Air Force were flown on 16 September, when three Lebanese Hunters, backed by a squadron of French Navy's Super Etendards from the aircraft carrier Clemenceau made an attempt to bomb and strafe Druze PLA and Syrian Army gun emplacements in the Chouf. However, the Druze were awaiting for them with an array of Syrian-supplied air defense systems, comprising SA-7 Grail surface-to-air missiles,[63] M1939 (61-K) 37mm and AZP S-60 57mm anti-aircraft guns, and Zastava M55 A2 20mm, ZPU-1, ZPU-2 and ZPU-4 14.5mm and ZU-23-2 23mm autocannons.[61] One Hunter was shot down by a SA-7 and the pilot barely managed to eject himself into the sea, being rescued by a U.S. Navy vessel. The second Hunter was heavily damaged by ground fire and made a forced landing at Halat. The third did not return to the base but flew straight to the RAF airbase at Akrotiri, Cyprus, where the pilot eventually requested political asylum upon arrival.[64] Two days later, on 18 September, the Lebanese Air Force Hunters flew another combat sortie against Druze positions in the Chouf, and on the following day, 19 September, a Lebanese Scottish Aviation Bulldog two-seat training aircraft flying on a reconnaissance mission over the Chouf was hit by ground fire and crashed near Aley, killing its two pilots.[65]

Lt. Gen. Tannous then requested urgent military support from the United States to its beleaguered LAF units fighting at Souk El Gharb. At first, the Americans refused but eventually agreed when they were told that this strategically valuable town was in danger of being overrun.[66] The United States Navy nuclear-powered missile cruiser USS Virginia, the destroyer USS John Rodgers, the frigate USS Bowen, and the destroyer USS Arthur W. Radford fired 338 rounds from their 5-inch (127 mm) naval guns at the Druze PLA positions, and helped the Lebanese Army hold the town until an informal ceasefire was declared on 25 September at Damascus, the day the battleship USS New Jersey arrived at the scene.[61] Although the Lebanese Army had beaten the Druze forces on the battlefield, it remains an open question whether they would have held Souk El Garb without the American naval support.[67][68] Moreover, it was a pyrrhic victory for the Lebanese Armed Forces,[61] for it marked the beginning of a confessional split in their ranks. Just prior to the cease-fire, Gen. al-Hakim, LAF Chief-of-Staff and commander of the predominantly Druze Seventh Brigade, fled into PSP-held territory but he would not admit he had actually defected.[61][69] In response to a request from Walid Jumblatt to neutralize the Army,[70][12] some 800 Druze regular soldiers from the primarily Druze Eleventh Brigade deserted their command at Hammana and Beiteddine,[71] whilst another 1,000 Druze soldiers from the same unit refused to leave their barracks by order of their own commander, Colonel Amin Qadi.[70][72]

Geneva Reconciliation Talks

The 25 September cease-fire temporarily stabilized the situation. The Gemayel government maintained its jurisdiction over west Beirut districts, the Shia Amal movement had not yet fully committed itself in the fighting, and Jumblatt's PSP/PLA remained landlocked in the Chouf Mountains. The Lebanese government and opposition personalities agreed to meet in Geneva, Switzerland, for a national reconciliation conference under the auspices of Saudi Arabia and Syria, and chaired by President Gemayel to discuss political reform and the May 17 Agreement.

For its part, the United States found itself carrying on Israel's role of shoring up the precarious Lebanese government.[61] An emergency arms shipment had been dispatched earlier on 14 September to beleaguered LAF units fighting in the Chouf, which were backed by air strikes and naval gunfire from the battleship USS New Jersey. On 29 September, the U.S. Ambassador's residence in east Beirut was hit by shell-fire and in response, the U.S. Marines' contingent stationed at Beirut International Airport was ordered to use their M198 155mm howitzers in support of the Lebanese Army.[73] That same day, the United States Congress, by a solid majority, adopted a resolution declaring the 1973 War Powers Resolution to apply to the situation in Lebanon and sanctioned the U.S. military presence for an eighteen-month period. U.S. vice-president George H. W. Bush made clear the position of the Reagan administration by demanding that Syria "get out from the Lebanon". A large naval task-force of more than a dozen vessels was assembled off the Lebanese coast and an additional contingent of 2,000 U.S. Marines was sent to the country. The United States Department of Defense (DoD) stated that the increase of its military forces in the eastern Mediterranean had been carried out to "sent a message to Syria".[74]

October 1983

American position

Many international observers believed that these measures implemented by the U.S. government were meant to reshape the power balance in the region in favor of the Amin Gemayel administration, to the detriment of the Syrians and their Lebanese allies.[75] The United States was now perceived in many circles as another foreign power attempting to assert its influence in Lebanese affairs by force, just as Israel and Syria had done.[76]

Alarmed by this American posture (which compromised the neutrality of the Multinational Force) and fearing for the safety of their own MNF contingents in Lebanon, the British, French and Italian governments expressed their concerns, insisting with the Reagan administration to restrict its activities in the region to the protection of Lebanese civilians and to stop supporting what they considered an ongoing assault of the Gemayel government on his own people.[77] However, President Reagan refused to modify his intransigent position and on 1 October, another shipment of arms was delivered to the Lebanese Army, which included M48A5 main battle tanks (MBTs), additional M113 armored personnel carriers (APCs) and M198 155mm long-range howitzers.[73] That same day, Walid Jumblatt announced the formation of a separate governmental administration for the Chouf, the "Civilian Administration of the Mountain" (CAM or CAOM), and called for the mass defection of all Druze elements from the Lebanese Armed Forces.[78] A few days later, the Druze LAF Chief-of-Staff and commander of the Seventh Brigade, General Nadim al-Hakim, returned to the Saïd el-Khateeb Barracks at Hammana along with the 800 Officers, NCOs and enlisted men who had deserted previously from the predominately Druze Eleventh Brigade, and announced his decision to remain in the Chouf, while his troops took sides with the Druze PSP/PLA.

The delivery of arms shipments was complemented by naval artillery barrages. Steaming to within two miles of the Lebanese coast, the battleship USS New Jersey, the destroyer USS John Rodgers and the nuclear-powered cruiser USS Virginia fired from their 5-inch naval guns some six-hundred 70 lb shells into the wooded hills above Beirut.[79] Unfortunately, the U.S. Navy eschewed proper reconnaissance and without sending Forward air controllers to help spot accurately Druze PLA and Syrian Army positions, most of the shells missed their targets and fell in Shia- and Druze-populated sub-urban areas located on the edge of west Beirut and the western Chouf, causing hundreds of civilian casualties.[80] For many Lebanese Muslims, this was the last straw – any illusion of U.S. neutrality had been dispelled by these recent developments and the MNF soon found itself exposed to hostile fire.

MNF barracks bombing

Early in the morning of 23 October, a suicide truck bomb struck the U.S. Marines' Battalion Landing Team 1/8 (BLT, part of the 24th Marine Amphibious Unit or MAU) building at Beirut international airport, killing 245 American servicemen and wounding another 130 marines and U.S. Navy personnel,[81][26] followed a few minutes later by the mysterious implosion of the French 3rd company, 1er RCP Paratrooper's Barracks at the 'Drakkar' apartment bloc in the Ramlet al-Baida quarter of Bir Hassan, Ouza'i district, which claimed the lives of 58 French paratroopers.[73][78][82] Again, the Shi'ite Islamic Jihad claimed responsibility for the bombing of the BLT building at the airport (but not of the 'Drakkar' apartment bloc) and warned of further attacks.[76][83]

The French promptly responded to the bombings with air strikes against Islamic Jihad targets in the Beqaa Valley. French Super Etendards from the aircraft carrier Foch retaliated by striking Nebi Chit, thought to house the Islamic Amal (a splinter faction of the Amal movement), and also the Iranian Revolutionary Guards' base at Ras el-Ain near Baalbek, but failed to hit the facilities and did only minor damage.[84] They also struck at Syrian Army's and Druze PLA positions in the Chouf region while U.S. warships kept up their artillery barrages against Syrian and Druze gun emplacements overlooking Beirut.[85]

November 1983

These retaliatory measures failed to put an end to the bomb attacks however, and on 4 November the Israeli Military Governor's Headquarters in Tyre was destroyed by a suicide truck-bombing, which cost the lives of 46 Israeli soldiers. Later that day, the Israeli Air Force (IAF) retaliated with air strikes against Palestinian positions near Baalbek in the Syrian-controlled Beqaa Valley, despite the fact that responsibility for the attack had been claimed by the Iranian-backed Lebanese Shia Islamic Jihad and not the PLO.[76]

On 10 November, a French Super Etendard narrowly escaped from being shot down by an SA-7 near Bourj el-Barajneh refugee camp in southwest Beirut while flying over Druze PSP/PLA positions.[86] The Israelis conducted additional retaliatory air strikes on 16 November, hitting a training camp in the eastern Beqaa Valley. The next day, French Super Etendards carried out similar strikes against another Islamic Amal camp in the vicinity of Baalbek.

Persistent and occasionally heavy fighting in the southwestern suburbs of Beirut between the Lebanese Army and the Shia Amal militia continued throughout November. As the month ended, the Chouf District continued to be the scene of frequent artillery and mortar exchanges between the LAF and Druze PSP/PLA forces, complemented by violent clashes at Souk El Gharb, Aytat and other places in the region. The IAF continued to carry air strikes on hostile targets in the Chouf on 20–21 November, striking at Bhamdoun, Soufar, Falougha-Khalouat, Ras el Haref, Ras el Matn, Baalechmay and Kobbeyh, losing a Kfir fighter-bomber jet, most probably to an SA-7, near Bhamdoun (the pilot was rescued by the Lebanese Army).[87][88][89][90] On 30 November, renewed artillery bombardments forced the closure of the Beirut International Airport in Khalde.[91]

December 1983

American-Syrian confrontation in the Chouf

Diplomatic tensions between Syria and the United States escalated to direct confrontation in early December when, despite numerous warnings from Washington, Syrian anti-aircraft batteries fired on a pair of U.S. Navy Tactical Airborne Reconnaissance Pod System (TARPS)‑equipped Grumman F-14A Tomcat fighter jets of Strike Fighter Squadron 31 (VFA-31) from the aircraft carrier USS John F. Kennedy flying on a reconnaissance mission over a section of the Beirut-Damascus Highway in the Syrian-controlled Beqaa Valley.[92][93] Determined to send a clear message to Syrian President Hafez al-Assad, the Americans retaliated with an hastily devised air raid on 4 December, when twenty-eight Grumman A-6E Intruder and Vought A-7E Corsair II fighter-bombers, supported by a single E-2C Hawkeye, two EA-6B Prowlers and two F-14A fighter jets, took off from the aircraft carriers USS Independence and USS John F. Kennedy, flashed inland over Beirut and headed for eight Syrian Army and Druze PLA installations, anti-aircraft artillery (AAA) sites and weapons' depots near Falougha-Khalouat and Hammana, within an eight-mile (12.87 km) corridor 20 miles (32.29 km) east of the Lebanese Capital. The list of selected targets included a Syrian-operated Stentor battlefield surveillance radar, Syrian tanks, three artillery sites (which had 28 gun emplacements between them) manned by the Syrian Army's 27th Artillery Brigade dug in near the village of Hammana and positions held by the pro-Syrian As-Sa'iqa Palestinian guerrilla faction[94] in the Beqaa Valley, close to the Syrian border.[95]

As a demonstration of American resolve, however, the hurriedly-executed raid was a fiasco – once over their targets in the Chouf, the U.S. fighter-bombers dispersed and pounded Syrian Army and Druze PLA positions but ran into a heavy barrage of anti-aircraft fire, so intense that the smoke in the sky rivalled that from the bomb blasts below.[96] According to the U.S. Defense Department, the barrage included a volley of about 40 surface-to-air missiles[94] and Flak fire from 150 anti-aircraft guns of various calibers, which filled the air with flame and smoke during the entire attack.[97] The U.S. Navy aircraft were opposed by an intimidating array of Soviet-supplied AAA systems comprising ZPU-1, ZPU-2 and ZPU-4 14.5mm and ZU-23-2 23mm autocannons mounted on technicals and Gun trucks, M1939 (61-K) 37mm and AZP S-60 57mm anti-aircraft guns in fixed positions, and plenty of highly mobile, radar‑directed ZSU-23-4M1 Shilka SPAAGs surrounding Beirut, plus man-portable SA-7 Grail and vehicle-mounted SA-9 Gaskin surface-to-air missiles.[98]

Two American planes, one A-6E and an A-7E, were shot down by Syrian SA-7 Grail or SA-9 Gaskin missiles. The Pilot of the A-6E, Lieutenant Mark A. Lange, ejected himself too late and was killed when his parachute failed to open properly while his Bombardier/Navigator, Lt. Bobby Goodman managed to bail out successfully and was taken prisoner by Syrian troops and Lebanese civilians when he touched the ground;[99][100][95] their crippled plane crashed near the town of Kafr Silwan, located in the mountains of the Syrian-controlled portion of the Matn District. More fortunate was the Pilot of the A-7E, Commander Edward T. Andrews, the leader of Carrier Air Wing One (CVW-1) who was searching for the downed Intruder crew: although he suffered minor injuries, was able to eject and landed in the Mediterranean, where he was rescued by a Christian fisherman and his son who in turn handed him over to the U.S Marines.[99][100][101] In flames, his stricken A-7E wavered for a moment in the air, and then exploded over the village of Zouk Mikael in the Keserwan District, 12 miles (19.31 km) northeast of Beirut International Airport, killing one Lebanese woman and injuring her three children when the debris crashed into their house;[102] a third plane, also an A-7E, suffered tailpipe damage, apparently from an SA-7 or SA-9.[96][103][76][85][97]

The bomb damage inflicted was difficult to assess. Although the U.S. Navy planes dropped some 24,000 lbs of ordnance – including 12 CBU‑59 Cluster Bombs and 28 MK-20 Rockeye "smart" bombs out of a total of 150 – and the complete target set had been engaged by the air strikes, the Syrians claimed that only an ammunition dump and an armored car were destroyed, and two people were killed and eight were wounded.[94] While the results had officially been described as 'effective', professionally, the event was viewed as nothing short of a failure.[101] There were no further American air strikes; instead, only artillery barrages from U.S. Navy warships and from U.S. Marines positions in the Beirut International Airport would be sanctioned against Syrian and Druze gun emplacements in the Chouf.[76]

The evacuation of Souk El Gharb and Deir el-Qamar

On 4 December, PSP leader Walid Jumblatt, ostensibly as a gesture of goodwill on humanitarian grounds and without any preconditions, offered to lift the sieges of Souk El Gharb and Deir el-Qamar, which had been cut off since September and had to rely on weekly International Red Cross (IRC) relief convoys for food and medical supplies. The Israelis underscored the extent of their responsibility for their Lebanese allies on 15 December when they stepped in to help the IRC in the evacuation of some 2,500 Christian Lebanese Forces (LF) militiamen and 5,000 civilians from Deir el-Qamar and Souk El Gharb. IDF armor and mechanized infantry units provided cover for the exodus towards the Israeli-controlled Awali River line.[87] There were some tense moments as Druze PLA militiamen, waving their rifles, jeered the LF fighters, who had been bundled into Israeli military trucks. The Christian fighters and the civilian refugees were eventually taken by ship by the Israeli Navy from the Israeli-occupied port of Sidon to Christian-controlled areas around Beirut.[104][87]

Meanwhile, on 14–15 December, as this evacuation was taking place, the battleship USS New Jersey fired its 5-inch naval guns in support of the Lebanese Army, shelling Druze PSP/PLA positions at Choueifat in the Chouf and Syrian Army positions at Dahr el Baidar and the Upper Matn district. The next day, 16 December, all the parties involved in the conflict agreed upon a new ceasefire, which finally allowed the Beirut International Airport to reopen its runway.[105]

In west Beirut, violent clashes erupted in mid-December between the Amal Movement and the Lebanese Army at Chyah and Bourj el-Barajneh, and again on 24 December when Lebanese Army detachments attempted to occupy strategic positions just vacated by the departing French MNF contingent at Sabra-Shatila, situated on the road leading to the Beirut International Airport. This time the Druze PLA joined Amal in the fighting, forcing the battered government forces to withdraw to east Beirut after a five-day street battle.[106]

January 1984

On 5 January, the Lebanese Government announced that a disengagement plan to demilitarize Beirut and its environs had been approved by Israel, Syria, the Lebanese Forces, and the Shia Amal and Druze PSP/PLA militias. However, implementation of the plan was delayed by continual inter-factional fighting in and around the Lebanese Capital and in the Chouf, but also in Tripoli. Earlier that month, both Walid Jumblatt and Nabih Berri demanded that the Lebanese Army units should return to their barracks and abstain from getting involved in the ongoing internal conflicts; they also demanded the abrogation of the 17 May agreement with Israel. Such demands were accompanied by another round of heavy fighting around Souk El Gharb, Dahr al-Wahsh, Kaifun, Kabr Chmoun, Aramoun, Khalde and the southern edge of Beirut, during which the Lebanese Army units positioned at these locations managed to blunt the Shia Muslim-Druze-LNSF drive towards the western districts of the Lebanese Capital.[107]

As sporadic fighting broke out again on 16 January, there were fears that the informal cease-fire that had generally prevailed since late September 1983 was breaking down. Druze PLA artillerymen again shelled Christian-controlled east Beirut and the Marines positions around the International Airport, with Amal and the Lebanese Army joining at the fringes.[108] This in turn provoked a response from the 5-inch naval guns of the battleship USS New Jersey and the destroyer USS Tattnall, firing at Druze gun emplacements in the hills surrounding Beirut.[109]

February 1984

The Beirut security plan

As the month of February opened, it became painfully clear that the Lebanese Government and its Armed Forces were now faced with an ominous political and military situation. Artillery and mortar exchanges continued since mid-January between the Christian-held east Beirut districts and the Muslim-controlled west Beirut quarters, the Chouf and the Beqaa, from which Syrian troops still provided logistical support to their Druze, Amal and LNSF allies. Determined to keep Beirut unified under Government control and to prevent the return of the militias to both western and eastern sectors of the Lebanese capital, Lt. Gen. Ibrahim Tannous ordered Lebanese Army troops to take up positions along the Green Line in the city center and its eastern approaches, being bolstered at some locations by Lebanese Forces militiamen. Despite this disadvantageous situation, the LAF Command decided nevertheless to reunify the Lebanese capital by implementing a hastily devised security plan, which called for the deployment of eight Lebanese Army mechanized infantry brigades throughout the Greater Beirut area, placed under the overall command of General Zouheir Tannir. In order to implement this security plan, the LAF Brigades were structured as follows:[110]

- The Third Brigade, under the orders of Colonel Nizar Abdelkader was positioned at the Hadath and the Faculty of Sciences sectors leading to the southern suburbs of Beirut.

- The Fourth Brigade, under the command of Colonel Nayef Kallas was deployed at the towns of Khalde, Aramoun, Kabr Chmoun and Shahhar, being entrusted with the mission of defending the southern approaches of Beirut.

- The Fifth Brigade, under the orders of Colonel khalil Kanaan was positioned at the Sin el Fil suburb east of Beirut in the Matn District as a reserve force, and the Brigade's primary mission was to provide support to the other Lebanese Army Brigades deployed in the Greater Beirut area.

- The Sixth Brigade, under the command of Colonel Lufti Jabar was tasked with the primary mission of maintaining order and security in west Beirut.

- The Seventh Brigade, provisionally under the orders of Colonel Issam Abu Jamra was deployed at Achrafieh and Hadath in east Beirut, and at Dahr al-Wahsh facing Aley in the Chouf District, where they faced the main anti-government Druze militia, the People's Liberation Army (PLA) of the Progressive Socialist Party (PSP).

- The Eight Brigade, under the command of Colonel Michel Aoun remained positioned at Souk El Gharb, Kaifun and Bsous facing the Druze PSP/PLA militia, being tasked with the primary mission of defending the south-eastern approaches to east Beirut, including Baabda.

- The Ninth Brigade (still being formed), under the orders of Colonel Mounir Merhi was deployed at the Hazmiyeh and Sin el Fil eastern suburbs of Beirut as a reserve force.

- The 10th Airmobile Brigade (also still being formed), reinforced by a Lebanese Army Commando battalion (Arabic: Fawj al-Maghaweer) led by then Major Youssef Tahan, under the command of Colonel Nassib Eid was held in reserve at east Beirut, ready to support the LAF Brigades in the field as required.

The February 6 Intifada and the fall of West Beirut

Earlier on 1 February, Walid Jumblatt denounced the Lebanese Government's disengagement plan as a waste of time, while its Druze PLA troops linked the following day with Nabih Berri's Amal militia units in order to attack Lebanese Army positions in the Greater Beirut area, which marked the beginning of the battle for the Lebanese Capital.[111] On 3 February, a combined Druze PLA/Amal full-scale offensive operation was mounted against Lebanese Army positions in the southern and eastern districts of the city, while fighting also erupted in the central area.[112]

At west Beirut tensions remained high, particularly between the Lebanese Army and the Shia militiamen of the Amal Movement, who feared that the LAF Command was planning to launch a large-scale operation against their strongholds in the Shia-populated Chyah, Bir Abed, Bir Hassan, Ouza'i and Khalde southwestern suburbs, where they had firmly entrenched themselves. All what was needed was the spark, and hostilities began three days later on 6 February, when the LAF Command of the Greater Beirut area decided to send the 52nd Infantry Battalion from the Fifth Brigade in M113 APCs supported by a Tank squadron provided with M48A5 MBTs on a routine patrol mission, whose planned route was to pass through the Dora suburb, the Museum crossing in the Corniche el Mazraa, the Barbir Hospital in the Ouza'i district, the Kola bridge, and the Raouché seafront residential and commercial neighbourhood. Alerted by the presence of such a large military force entering west Beirut – which they viewed suspiciously as being abnormally reinforced for a simple routine mission – Amal militia forces misinterpreted this move as a disguised attempt by Government forces to seize the southwestern suburbs of the Lebanese capital by force. An alarmed Amal Command promptly issued a general mobilization order in the ranks of its militia, and as soon as the Lebanese Army patrol arrived at the Fouad Chehab bridge near the Barbir Hospital, they fell into an ambush. Several M48 Tanks that were leading the column were hit by dozens of RPG-7 anti-tank rounds, which brought the advance of the entire patrol to a halt.[113]

Faced with the gravity of the situation, the LAF Command reacted by ordering a reposition of its combat units stationed in the Greater Beirut area and by setting up a new demarcation line across the western and eastern sectors of the Lebanese capital. Situated on portions of the old Green Line, this new line went from the Port district located on the eastern part of the Saint George Bay to the town of Kfarshima in the Baabda District, and was designed to deny the Muslim LNSF and Christian LF militias any opportunity to gain control over both sectors of Beirut and at the same time, to act as a buffer between them. In addition, the Lebanese Army units present at west Beirut were reinforced by the 91st Infantry Battalion and the 94th Armoured Battalion from the Ninth Brigade, under the command of Colonel Sami Rihana. Placed at the disposal of the Seventh Brigade's Command, these two battalions were positioned between the Port district and the Sodeco Square in the Nasra (Nazareth) neighbourhood of the Achrafieh district of east Beirut.[114]

That same day, the Muslim militias rose in an uprising, which became known as the February 6 Intifada, when heavy clashes erupted at the Museum crossing in the Corniche el Mazraa between Army units and Amal militia forces, and the fighting quickly spread throughout west Beirut, escalating into the 'Street War' (Arabic: حرب شوارع | Harb Shawarie). Hundreds of Shia, Sunni and Druze militiamen from Amal, the PSP/PLA, Al-Mourabitoun and other LNSF factions armed with automatic small-arms and RPG-7 anti-tank rocket launchers, and backed by technicals took to the streets, mounting combined ground assaults against all the positions held by the Army brigades deployed in the western sector of the Lebanese capital. This forced the LAF Command to alter its previously established demarcation line separating Beirut, and although still running from the Port district to Kfarshima, it was re-adjusted to include the Museum crossing area, the Galerie Semaan and Mar Mikhaël, a residential and commercial neighbourhood in the Medawar district. By the end of the day, amidst intense shelling, the Shia Amal and the Druze PLA took control over west Beirut in a matter of hours, seizing in the process the main Government-owned Television and Radio broadcasting stations' buildings.[114]

Although forced out of the Chyah quarter by Amal, the Lebanese Army launched three days later, on 9 February, a combined counter-offensive with the Lebanese Forces on the Shia-populated southwestern suburbs of the Lebanese capital. The PSP/PLA-Amal alliance forces promptly reacted that same day by mounting simultaneous ground assaults against Government and LF-held positions in the city center along the Green Line, and on the southern and eastern districts. After two days of the heaviest fighting in Beirut since the 1975-76 civil war, the combined Druze PLA/Amal militia forces managed to drive Lebanese Army and LF units out of west Beirut, largely due to the refusal of Shia Muslim soldiers to fight their coregionalists – in fact some actually fought against their own Army units.[115][114] On 8–9 February, in the heaviest shore bombardment since the Korean War,[116] a massive artillery barrage by offshore U.S. warships pounded Druze PLA and Syrian positions in the hills overlooking Beirut, an operation that invoked the disapproval of the U.S. Congress.[112] During a nine-hour period on 8 February, the battleship USS New Jersey alone fired a total of 288 16-inch rounds, each one weighing as much as a Volkswagen Beetle, hence the nickname of "flying Volkswagens" given by the Lebanese to the huge shells that struck the Chouf.[117] Once again, some of these shells missed their intended targets and killed civilians, mostly Shiites and Druze.[118] In addition to destroying Syrian and Druze PLA artillery and missile sites, thirty rounds hit a Syrian command post, killing the general commanding the Syrian forces in Lebanon along with several of his senior officers.[119]

The Lebanese Army's defeat in the Chouf

Meanwhile in the Chouf, on 13 February the local Druze PLA forces and their LNSF allies drove the last remaining Lebanese Army and LF units from the towns of Aley, Kfarmatta and others, with only Souk El Gharb remaining firmly in Government hands.[120] On that same day, an Amal force also succeeded in driving out other Lebanese Army units from their positions in the southern approaches to west Beirut, seizing Khalde (with the exception of the adjoining International Airport, still being held by the U.S. Marines).[121] The Lebanese Air Force Hawker Hunter jets flew their last combat sortie over the Chouf, carrying out air strikes against advancing Druze PLA forces on the western portion of the Shahhar region in support of the Fourth Brigade's units reinforced by the 101st Ranger Battalion from the 10th Airmobile Brigade[122] fighting desperately to retain their positions at Aabey, Kfarmatta, Ain Ksour, and Al-Beniyeh, which achieved little success due to poor planning and lack of coordination with Lebanese Army units fighting on the ground. This situation was exacerbated by the fact that LNSF militias managed to intercept, alter, and retransmit Lebanese Army radio communications, which allowed them to impersonate the LAF command in east Beirut by ordering Fourth Brigade units to retreat to safer positions. Simultaneously, they ordered Lebanese Army's artillery units positioned at east Beirut to shell their own troops' positions in the western Chouf, which wreaked havoc among Fourth Brigade units and forced them to fall back in disorder towards the coast while being subjected to friendly fire.[122]

During the following two days, Amal militia forces moved against Lebanese Forces positions in the Iqlim al-Kharrub coastal enclave, reaching Damour after meeting little resistance and on 14 February, they linked up at Khalde with their Druze PSP/PLA allies to drive the Fourth Brigade from their remaining positions in the western Shahhar region 3½ miles (about 4 km) south to the vicinity of Damour and Es-Saadiyat, in the Iqlim al-Kharrub coastal enclave, as they attempted to create a salient from Aley to the coast at Khalde, south of Beirut.[121] Surrounded and badly mauled, the Brigade disintegrated when approximately 900 Druze enlisted men, plus 60 Officers and NCOs, deserted to join their coreligionists of Jumblatt's PSP or SSNP militias.[121] The remaining 1,000 or so Maronite Officers and men either withdrew to the coast, regrouping at the Damour – Es-Saadiyat area or fled south across the Awali River, seeking protection behind Israeli lines while leaving behind some U.S.-made tanks and armored personnel carriers, jeeps, trucks, Howitzers and ammunition.[123] After reaching Damour and Sidon, the soldiers were evacuated by sea under the auspices of the Lebanese Navy to east Beirut, where they enrolled in the 10th Airmobile Brigade[124] and other Christian-dominated army units.[121][125]

The next day, the towns of Mechref and Damour fell under the control of the PSP/PLA, while violent clashes raged around Souk El Gharb, the last government-held stronghold in the Chouf mountains. By this time, hordes of panic-stricken Lebanese civilian refugees were fleeing towards Israeli-held territory south of the Awali River line, accompanied by a large number of dispirited Lebanese Army soldiers and LF militiamen. West Beirut and the Chouf had fallen to the Shia Amal, the Druze PLA and LNSF militias backed by Syria, and both the Lebanese Armed Forces and the Lebanese Forces had been decisively defeated.[126]

Collapse of the LAF

The decisive defeat of the Lebanese Armed Forces on two key fronts led it once again to disintegrate along sectarian lines, as many demoralized Muslim soldiers began to defect to join the opposition or confined themselves to barracks. It is estimated that 40% of the Lebanese Army's 27,000 active fighting men had gone over to support the Muslim militias or refused to take part in any further fighting against them.[127] Following an open appeal by Nabih Berri, the predominantly Shia Sixth Brigade deserted en bloc to Amal, being subsequently enlarged from 2,000 to 6,000 men by absorbing Shia deserters from other Army units, which included the 97th Battalion from the Seventh Brigade.[112][128][114]

The Multinational Force begin its withdrawal

As these events were unfolding in Beirut, the U.S. President Ronald Reagan was pressured for a complete withdrawal of the U.S. contingent of the MNF from Lebanon by the U.S. Congress. These calls were increased after the Lebanese Sunni Prime minister Shafik Wazzan and his entire cabinet resigned on 5 February, but was persuaded by President Amin Gemayel to remain as caretaker.[112] Two days later, Reagan ordered 1,700 Marines to be transferred to U.S. Navy vessels lying offshore, leaving just a small force of Marines from BLT 3/8, the ground combat element of the 24th Marine Amphibious Unit, as part of the External Security Force assigned to guard the replacement U.S. Embassy in east Beirut until their withdrawal on 31 July. The American detachment began to be withdrawn on 17 February; the British, French and Italian detachments followed suit[129] – the Italians pulled out on 20 February, followed by the rest of the U.S. Marines detachment on 26 February.[130] Amal militiamen took over their vacant positions, including those at the International Airport, which were handed over to the Sixth Brigade.[130] The positions that the French had held along the Green Line, parts of which had already been taken over by the Amal, the Druze PLA and the Lebanese Forces, were eventually handed over to a specially formed force of Internal Security Forces (ISF) gendarmes and recalled Lebanese Army reservists.[131]

Faced with the crushing defeat and subsequent collapse of the LAF, and with his own status effectively reduced to that of Mayor of East Beirut, President Amin Gemayel had no choice but to go on 24 February in an official trip to Damascus and consult the Syrian President Hafez al-Assad on the future of Lebanon. Naturally, he was first required to renounce the American-sponsored 17 May Agreement with Israel.[76][29]

March 1984

After a peace plan put forward by Saudi Arabia and accepted by President Amin Gemayel was rejected by Syria, Israel and the main Lebanese political parties (the Kataeb, NLP and the Druze PSP), the Lebanese Government on 5 March formally cancelled the 17 May agreement, which it had not even ratified; the last U.S. Marines departed a few weeks later. The second round of the reconciliation talks began on 12 March in Lausanne, Switzerland, again chaired by President Gemayel. On 20 March, at the closing session of the conference the participants issued a declaration calling for an immediate ceasefire, which had in fact been generally observed since the defeat of the LAF and LF in late February, and established a higher security committee to supervise the disengagement of opposing factions and the demilitarization of Beirut.

That same day, as soon as the declaration from the Lausanne conference was announced, the central districts of the Lebanese capital along the Green Line and the southern suburbs flared up again, with the fighting lasting throughout the night of 20–21 March.[132] Firing across the Green Line continued spasmodically, and on 22 March Druze PLA militiamen backed by Amal drove their erstwhile allies of the Sunni Al-Mourabitoun militia and other smaller factions from their positions in the area, ostensibly to prevent any violations of the ceasefire.[133][134] Their mission at an end, the last French troops of the MNF left Beirut on 31 March.[82] The "Mountain War" was over.

The defeat of the LAF and the Lebanese Forces in the Mountain War was catastrophic for the Maronite Christian community, and came with a cost in political currency and territorial losses.[61] It was clear that the LAF Commander-in-Chief Lt. Gen. Ibrahim Tannous and the LF Command Council headed by Fadi Frem and Fouad Abou Nader in East Beirut had grossly underestimated the military strength and organizational capabilities displayed by the Druze and their allied Sunni and Shia Muslim militias of the LNSF coalition, as well as the political and logistical support they would receive from Syria and the PLO.

Moreover, President Amine Gemayel's miscalculation by refusing to grant the Lebanese Druze and Shia Muslim communities the expected political representation, and his excessive reliance on American and French political and military support during the conflict that ensued, seriously undermined his own credibility and authority in his dual role as head of state and leader of the Maronite Christian community. For their part, the war inflicted a heavy blow to the Lebanese Forces' prestige and credibility, due to their arrogant behavior towards the Muslim and Druze civilian population and their incapacity to protect the Christian communities of the Chouf District.

The Mountain War also contributed to shatter the illusion that the Lebanese Civil War had been settled in 1976,[61] a view shared by many Lebanese Christian and Muslim political factions and militias, who believed that the withdrawal of all foreign forces (meaning the Israelis, Syrians and Palestinians) would bring a decisive end to the ongoing conflict, which they regarded as a "war between foreigners". In the end, their hopes were dashed when the MNF pulled out and the Israelis withdrew to southern Lebanon to establish a "Security Belt", which enabled Syria to consolidate its hold on Lebanon. However, the resulting power vacuum proved difficult to fill, even for the Syrians, and the country remained split and in turmoil for years to come.

In August 2001, Maronite Catholic Patriarch Nasrallah Boutros Sfeir toured the predominantly Druze Chouf region of Mount Lebanon and visited Mukhtara, the ancestral stronghold of Druze leader Walid Jumblatt. The tumultuous reception that Sfeir received not only signified a historic reconciliation between Maronites and Druze, who fought a war in 1983–1984, but underscored the fact that the banner of Lebanese sovereignty had broad multi-confessional appeal[135] and was a cornerstone for the Cedar Revolution in 2005.

- 1983 United States embassy bombing in Beirut

- 1983 Beirut barracks bombing

- Battle of Tripoli (1983)

- Battle of the Hotels

- Damour massacre

- Lebanese Armed Forces

- Lebanese Forces

- List of weapons of the Lebanese Civil War

- Sabra and Shatila massacre

- St George's Church attack

- Syrian military presence in Lebanon

- Gordon, The Gemayels (1988), pp. 70–71.

- Hazran, Yusri (2013). The Druze Community and the Lebanese State: Between Confrontation and Reconciliation. Routledge. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-317-93173-7.

the Druze had been able to live in harmony with the Christian

- Artzi, Pinḥas (1984). Confrontation and Coexistence. Bar-Ilan University Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-965-226-049-9.

.. Europeans who visited the area during this period related that the Druze "love the Christians more than the other believers," and that they "hate the Turks, the Muslims and the Arabs [Bedouin] with an intense hatred.

- CHURCHILL (1862). The Druzes and the Maronites. Montserrat Abbey Library. p. 25.

..the Druzes and Christians lived together in the most perfect harmony and good-will..

- Hobby (1985). Near East/South Asia Report. Foreign Broadcast Information Service. p. 53.

the Druzes and the Christians in the Shuf Mountains in the past lived in complete harmony..

- O'Ballance, Civil War in Lebanon (1998), pp. 129; 138.

- Hinson, Crimes on Sacred Ground: Massacres, Desecration, and Iconoclasm in Lebanon's Mountain War 1983-1984 (2017), p. 51.

- Guest, Lebanon (1994), p. 109.

- Kechichian, The Lebanese Army: Capabilities and Challenges in the 1980s (1985), p. 26.

- Barak, The Lebanese Army – A National institution in a divided society (2009), pp. 123-125.

- Barak, The Lebanese Army – A National institution in a divided society (2009), pp. 117-118.

- "Lebanon - Mechanized Infantry Brigades". www.globalsecurity.org.

- Barak, The Lebanese Army – A National institution in a divided society (2009), p. 123.

- Guest, Lebanon (1994), pp. 102; 109.

- Guest, Lebanon (1994), p. 110.

- Hokayem, L'armée libanaise pendant la guerre: un instrument du pouvoir du président de la République (1975-1985) (2012), p. 78.

- Sex & Bassel Abi-Chahine, Modern Conflicts 2 – The Lebanese Civil War, From 1975 to 1991 and Beyond (2021), p. 101.

- Barak, The Lebanese Army – A National institution in a divided society (2009), p. 124.

- O'Ballance, Civil War in Lebanon (1998), pp. 120–121.

- O'Ballance, Civil War in Lebanon (1998), p. 121.

- O'Ballance, Civil War in Lebanon (1998), p. 122.

- Katz, Russel, and Volstad, Armies in Lebanon (1985), p. 34.

- O'Ballance, Civil War in Lebanon (1998), p. 123.

- Ménargues, Les Secrets de la guerre du Liban (2004), p. 498.

- Tueni, Une guerre pour les autres (1985), p. 294.

- DoD commission on Beirut International Airport December 1983 Terrorist Act

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - O'Ballance, Civil War in Lebanon (1998), p. 128.

- Friedman, Thomas L. (8 April 1984). "America's failure in Lebanon". The New York Times.

- Menargues, Les Secrets de la guerre du Liban (2004), p. 498.

- Gordon, The Gemayels (1988), p. 70.

- "Never-before-heard tapes of Reagan revealed". New York Post. 8 November 2014.

- O'Ballance, Civil War in Lebanon (1998), p. 129.

- Barak, The Lebanese Army – A National institution in a divided society (2009), p. 125.

- Gordon, The Gemayels (1988), p. 66.

- Menargues, Les Secrets de la guerre du Liban (2004), p. 472.

- Rabah, Conflict on Mount Lebanon: The Druze, the Maronites and Collective Memory (2020), p. 302.

- Collelo, Lebanon: a country study (1989), p. 210.

- Gordon, The Gemayels (1988), p. 69.

- Sex & Abi-Chahine, Modern Conflicts 2 – The Lebanese Civil War, From 1975 to 1991 and Beyond (2021), p. 77.

- Sex & Abi-Chahine, Modern Conflicts 2 – The Lebanese Civil War, From 1975 to 1991 and Beyond (2021), pp. 25; 76.

- Sex & Abi-Chahine, Modern Conflicts 2 – The Lebanese Civil War, From 1975 to 1991 and Beyond (2021), pp. 66-67.

- Olivier Antoine and Raymond Ziffredi, BTR 152 & ZU 23, Steelmasters Magazine, October–November 2006 issue, pp. 48–55.

- Kassis, Les TIRAN 4 et 5, de Tsahal aux Milices Chrétiennes, p. 59.

- Abi-Chahine, The People's Liberation Army Through the Eyes of a Lens, 1975–1991 (2019), pp. 6; 26.

- Kassis, 30 Years of Military Vehicles in Lebanon (2003), p. 58.

- Abi-Chahine, The People's Liberation Army Through the Eyes of a Lens, 1975–1991 (2019), pp. 53; 67.

- Abi-Chahine, The People's Liberation Army Through the Eyes of a Lens, 1975–1991 (2019), pp. 65-75.

- Abi-Chahine, The People's Liberation Army Through the Eyes of a Lens, 1975–1991 (2019), pp. 77; 81; 83.

- Sex & Bassel Abi-Chahine, Modern Conflicts 2 – The Lebanese Civil War, From 1975 to 1991 and Beyond (2021), p. 26.

- Kassis, 30 Years of Military Vehicles in Lebanon (2003), p. 61.

- Abi-Chahine, The People's Liberation Army Through the Eyes of a Lens, 1975–1991 (2019), pp. 77; 81.

- Abi-Chahine, The People's Liberation Army Through the Eyes of a Lens, 1975–1991 (2019), pp. 77; 82; 84-85.

- Mahé, La Guerre Civile Libanaise, un chaos indescriptible! (1975–1990) (2014), p. 81.

- Abi-Chahine, The People's Liberation Army Through the Eyes of a Lens, 1975–1991 (2019), pp. 76-80.

- Kassis, Les TIRAN 4 et 5, de Tsahal aux Milices Chrétiennes, p. 60.

- Salmon, Massacre and Mutilation: Understanding the Lebanese Forces through their use of violence (2004), p. 10, footnote 19.

- Laffin, The War of Desperation: Lebanon 1982-85 (1985), pp. 184-185.

- Hinson, Crimes on Sacred Ground: Massacres, Desecration, and Iconoclasm in Lebanon's Mountain War 1983-1984 (2017), p. 8.

- Al-Nahar (Beirut), 16 August 1991.

- Kanafani-Zahar, «La réconciliation des druzes et des chrétiens du Mont Liban ou le retour à un code coutumier» (2004), pp. 55-75.

- Collelo, Lebanon: a country study (1989), p. 211.

- Barak, The Lebanese Army – A National institution in a divided society (2009), p. 115.

- Guest, Lebanon (1994), p. 106.

- William E. Smith, Deeper into Lebanon, TIME Magazine, 26 September 1983.

- Hokayem, L'armée libanaise pendant la guerre: un instrument du pouvoir du président de la République (1975-1985) (2012), pp. 82-83.

- Friedman, From Beirut to Jerusalem (1990), page unknown.

- Dionne Jr., E. J. (21 September 1983). "In the Druse hills, a burst of anger is directed at U.S." The New York Times.

- Dionne Jr, E. J. (20 September 1983). "U.S. WARSHIPS FIRE IN DIRECT SUPPORT OF LEBANESE ARMY". The New York Times. No. 20 September 1983. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- O'Ballance, Civil War in Lebanon (1998), pp. 131–132.

- Collelo, Lebanon: a country study (1989), p. 225.

- Rolland, Lebanon: Current Issues and Background (2003), pp. 185-186.

- Brinkley, Joel (17 February 1984). "As the Lebanese Army caves in, U.S. evaluates training program; American effort said to have overlooked doubts of officers". The New York Times.

- Guest, Lebanon (1994), p. 111.

- Gordon, The Gemayels (1988), p. 75.

- Gordon, The Gemayels (1988), pp. 75-76.

- Katz, Russel, and Volstad, Armies in Lebanon (1985), p. 35.

- Gordon, The Gemayels (1988), p. 76.

- O'Ballance, Civil War in Lebanon (1998), p. 132.

- Smith, William E. (3 October 1983). "Helping to hold the Line". TIME Magazine. Archived from the original on 22 December 2008.

- Glass, Charles (July 2006). "Lebanon Agonistes". CounterPunch. Archived from the original on 5 January 2009. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- Russel and Carroll, The US Marine Corps since 1945 (1984), p. 32.

- Pivetta, Beyrouth 1983, la 3e compagnie du 1er RCP dans l'attentat du Drakkar, Militaria Magazine (2014), pp. 41-44.

- Trainor, Bernard E. (6 August 1989). "'83 Strike on Lebanon: Hard Lessons for U.S." The New York Times.

- O'Ballance, Civil War in Lebanon (1998), p. 133.

- "Disaster in Lebanon: US and French Operations in 1983". Acig.org. Archived from the original on 7 October 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- O'Ballance, Civil War in Lebanon (1998), p. 134. This source reports on the loss of an American-made F-16, though it was actually an Israeli made Kfir.

- "Israeli Plane Shot Down by Surface-to-air Missiles over Lebanon". 21 November 1983.

- Friedman, Thomas L. (21 November 1983). "Israeli Jets Bomb Palestinian Bases in Lebanon Hills". The New York Times.

- Hokayem, L'armée libanaise pendant la guerre: un instrument du pouvoir du président de la République (1975-1985) (2012), pp. 83-84.

- Micah Zenko (13 February 2012). "When America Attacked Syria". Politics, Power, and Preventive Action. Council on Foreign Relations. Archived from the original on 7 October 2014. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- Mersky, Crutch and Holmes, A-7 Corsair II Units 1975-91 (2021), p. 28.

- Ed Magnuson, Bombs vs. Missiles, TIME magazine, 12 December 1983.

- Mersky, Crutch and Holmes, A-7 Corsair II Units 1975-91 (2021), p. 31.

- Ed Magnuson, "Steel and Muscle": The U.S. strikes and the Syrians – and charts a new course with Israel, TIME magazine, 12 December 1983.

- Mersky, Crutch and Holmes, A-7 Corsair II Units 1975-91 (2021), p. 48.

- Mersky, Crutch and Holmes, A-7 Corsair II Units 1975-91 (2021), pp. 30-31.

- Tom Cooper & Eric L. Palmer (26 September 2003). "Disaster in Lebanon: US and French Operations in 1983". Acig.org. Archived from the original on 7 October 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- "2005". Ejection-history.org.uk. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- Mersky, Crutch and Holmes, A-7 Corsair II Units 1975-91 (2021), p. 49.

- Mersky, Crutch and Holmes, A-7 Corsair II Units 1975-91 (2021), pp. 48-49.

- William E. Smith, Dug In and Taking Losses, TIME magazine, 19 December 1983.

- William E. Smith, Familiar Fingerprints, TIME Magazine, 26 December 1983, p. 7.

- Hokayem, L'armée libanaise pendant la guerre: un instrument du pouvoir du président de la République (1975-1985) (2012), p. 84.

- O'Ballance, Civil War in Lebanon (1998), pp. 134–135.

- Hokayem, L'armée libanaise pendant la guerre: un instrument du pouvoir du président de la République (1975-1985) (2012), p. 85.

- O'Ballance, Civil War in Lebanon (1998), p. 136.

- William E. Smith, Murder in the University, TIME Magazine, 30 January 1984, pp. 14–15.

- Hokayem, L'armée libanaise pendant la guerre: un instrument du pouvoir du président de la République (1975-1985) (2012), pp. 85-86.

- Pivetta, Beyrouth 1983, la 3e compagnie du 1er RCP dans l'attentat du Drakkar, Militaria Magazine (2014), p. 44.

- O'Ballance, Civil War in Lebanon (1998), p. 137.

- Hokayem, L'armée libanaise pendant la guerre: un instrument du pouvoir du président de la République (1975-1985) (2012), p. 86.

- Hokayem, L'armée libanaise pendant la guerre: un instrument du pouvoir du président de la République (1975-1985) (2012), p. 87.

- Barak, The Lebanese Army – A National institution in a divided society (2009), p. 113.

- "USS New Jersey (BB 62)". navysite.de. Retrieved 27 May 2005.

- "U.S. warship stirs Lebanese fear of war". Christian Science Monitor. 4 March 2008.

- Glass, Charles (July 2006). "Lebanon Agonistes". CounterPunch. Archived from the original on 5 January 2009. Retrieved 17 October 2009.

- "U.S. Navy Battleships - USS New Jersey (BB 62)". www.navy.mil. Archived from the original on 29 May 2018. Retrieved 30 June 2019.

- Gordon, The Gemayels (1988), p. 78.

- Collelo, Lebanon: a country study (1989), p. 223.

- Hokayem, L'armée libanaise pendant la guerre: un instrument du pouvoir du président de la République (1975-1985) (2012), p. 88.

- Barrett, Laurence I. (27 February 1984). "Failure of a Flawed Policy". TIME Magazine. Archived from the original on 29 October 2010.

- Micheletti and Debay, La 10e Brigade Heliportée, RAIDS magazine (1989), p. 21 (box).

- Hokayem, L'armée libanaise pendant la guerre: un instrument du pouvoir du président de la République (1975-1985) (2012), pp. 88-89.

- O'Ballance, Civil War in Lebanon (1998), pp. 137-138.

- "Civilians Leaving: Shiite and Druse Leaders Call for a Cease-Fire — Marine Wounded", The New York Times, 8 February 1984, p. Al.

- Nerguizian, Cordesman & Burke, The Lebanese Armed Forces: Challenges and Opportunities in Post-Syria Lebanon (2009), pp. 56-57.

- Collelo, Lebanon: a country study (1989), p. 212.

- O'Ballance, Civil War in Lebanon (1998), p. 139.

- O'Ballance, Civil War in Lebanon (1998), pp. 139-140.

- Hokayem, L'armée libanaise pendant la guerre: un instrument du pouvoir du président de la République (1975-1985) (2012), pp. 89-90.

- O'Ballance, Civil War in Lebanon (1998), p. 140.

- Hokayem, L'armée libanaise pendant la guerre: un instrument du pouvoir du président de la République (1975-1985) (2012), p. 90.

- Nasrallah Boutros Sfeir, Meib, May 2003, archived from the original (dossier) on 11 June 2003

- Aïda Kanafani-Zahar, «La réconciliation des druzes et des chrétiens du Mont Liban ou le retour à un code coutumier», Critique internationale, n23 (2004), pp. 55–75. (in French)

- Afaf Sabeh McGowan, John Roberts, As'ad Abu Khalil, and Robert Scott Mason, Lebanon: a country study, area handbook series, Headquarters, Department of the Army (DA Pam 550-24), Washington D.C. 1989. -

- Alain Menargues, Les Secrets de la guerre du Liban: Du coup d'état de Béchir Gémayel aux massacres des camps palestiniens, Albin Michel, Paris 2004. ISBN 978-2-226-12127-1 (in French)

- Aram Nerguizian, Anthony H. Cordesman & Arleigh A. Burke, The Lebanese Armed Forces: Challenges and Opportunities in Post-Syria Lebanon, Burke Chair in Strategy, Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS), First Working Draft: 10 February 2009. –

- Bassel Abi-Chahine, The People's Liberation Army Through the Eyes of a Lens, 1975–1991, Éditions Dergham, Jdeideh (Beirut) 2019. ISBN 978-614-459-033-1

- Edgar O'Ballance, Civil War in Lebanon, 1975-92, Palgrave Macmillan, London 1998. ISBN 0-333-72975-7

- Éric Micheletti and Yves Debay, Liban – dix jours aux cœur des combats, RAIDS magazine No.41, October 1989, Histoire & Collections, Paris. ISSN 0769-4814 (in French)

- Ghassan Tueni, Une guerre pour les autres, Éditions JC Lattès, 1985. ISBN 978-2-7096-0375-1 (in French)

- Jago Salmon, Massacre and Mutilation: Understanding the Lebanese Forces through their use of violence, Workshop on the 'techniques of Violence in Civil War', PRIO, Oslo, 20–21 August 2004. –

- John C. Rolland (ed.), Lebanon: Current Issues and Background, Nova Science Publishers, Hauppauge, New York 2003. ISBN 978-1-59033-871-1 –

- John Laffin, The War of Desperation: Lebanon 1982-85, Osprey Publishing Ltd, London 1985. ISBN 0-85045-603-7

- Joseph A. Kechichian, The Lebanese Army: Capabilities and Challenges in the 1980s, Conflict Quarterly, Winter 1985.

- Joseph Hokayem, L'armée libanaise pendant la guerre: un instrument du pouvoir du président de la République (1975-1985), Lulu.com, Beyrouth 2012. ISBN 978-1-291-03660-2 (in French) –

- Ken Guest, Lebanon, in Flashpoint! At the Front Line of Today's Wars, Arms and Armour Press, London 1994, pp. 97–111. ISBN 1-85409-247-2