Natisone_Valley_dialect

Natisone Valley dialect

Slovenian language dialect

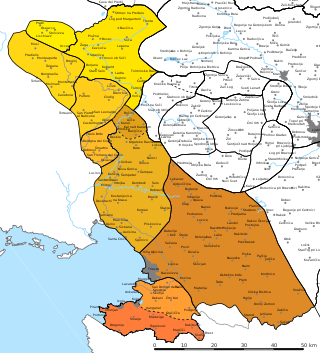

The Natisone Valley dialect (Natisone Valley: nedìško narèčje; Slovene: nadiško narečje [naˈdíːʃkɔ naˈɾéːt͡ʃjɛ],[1] nadiščina;[2] Italian: dialetto natisoniano[3]), or Nadiža dialect, is a Slovene dialect spoken mainly in Venetian Slovenia, but also in a small part of Slovenia. It is one of the two dialects in the Littoral dialect group to have its own written form, along with Resian. It is closely related to the Torre Valley dialect, which has a higher degree of vowel reduction but shares practically the same accented vowel system.[4] It borders the Torre Valley dialect to the northwest, the Soča dialect to the northeast, the Karst dialect to the southeast, the Brda dialect to the south, and Friulian to the west.[5] The dialect belongs to the Littoral dialect group, and it evolved from Venetian–Karst dialect base.[5][6]

| Natisone Valley dialect | |

|---|---|

| nedìško narèčje | |

| Pronunciation | nɛˈdiːʃkɔ naˈɾɛt͡ʃjɛ |

| Native to | Italy, Slovenia |

| Region | Natisone valley (Venetian Slovenia) |

| Ethnicity | Slovenes |

Indo-European

| |

Early forms | Northwestern Slovene dialect

|

| Dialects |

|

| Latin | |

| Official status | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| IETF | sl-nedis |

Natisone Valley dialect | |

The Natisone Valley dialect is a dialect of Slovene, an Indo-European language belonging to the western subgroup of the South Slavic branch of the Slavic languages. It is quite different from standard Slovene because the standard language is based on the Lower Carniolan and Upper Carniolan dialects,[7] which formed from the southeastern proto-dialect, whereas the Natisone Valley dialect formed from the northwestern proto-dialect and shows many similarities with other dialects in the Littoral dialect group.[8]

Nonetheless, the Natisone Valley dialect and standard Slovene are easily mutually intelligible. Even though the dialect has many words derived from Friulian, it can still be quite easily understood by most Slovene speakers, unlike the Torre Valley dialect and Resian.[9]

The dialect is mainly spoken in northeastern Italy, in Venetian Slovenia. It is spoken along four rivers: the Natisone (Slovene: Nadiža) and its three tributaries: the Alberone (Aborna), Cosizza (Kozica), and Erbezzo (Arbeč), up to San Pietro al Natisone (Špeter Slovenov).[10] In Slovenia, it encompasses the area west of the Kolovrat range, with villages including Ukanje and Kostanjevica (part of Lig), as well as villages around Livek. Larger towns can only be found in Italy, such as San Pietro al Natisone, Sanguarzo (Šenčur), Purgessimo (Prešnje), San Leonardo (Podutana), and Masseris (Mašere).[5]

The Natisone Valley dialect is rather uniform. The easternmost microdialects are the most different, having the phonemes /ə/ and /ʎ/, which are unknown to the other microdialects, and /m/ is sometimes used instead of /n/ at the end of a word. The biggest differences between the microdialects are the reflexes for Alpine Slovene *t’, which has almost merged with *č in the west, merging into /t͡ʃ/, with the first one usually being more palatalized. In the east, however, *t’ is still distinct and even pronounced as /t͡s/ at the end of a word.[11]

The Natisone Valley dialect has pitch accent on long syllables. It also differentiates between long and short syllables, both can occur anywhere in a word. There is, however, tendency to lengthen historically short vowels. Accent is on the same syllable as in Alpine Slavic, which is different from Standard Slovene, which has undergone *ženȁ → *žèna and optionally *məglȁ → *mə̀gla shifts (e. g. NV žená, SS žéna 'wife').[12]

Diacritics

Similarly to standard Slovene, the Natisone Valley dialect also has diacritics to denote accent. The accent is free and therefore it must be denoted with a diacritic. Three standard diacritics are used; however, they do not show tonal oppositions.

The three diacritics are:[3][13]

- The grave ( ` ) indicates a long vowel: à è ì ò ù (IPA /aː ɛː iː ɔː uː/).

- The acute ( ´ ) indicates a short vowel: á é í ó ú (IPA /a ɛ i ɔ u/).

- The dot above ( ˙ ) indicates an extra-short vowel: ȧ ė ȯ u̇ (IPA /ă ɛ̆ ɔ̆ ŭ/).

In addition, there is also the caron ( ˇ ), which indicates that a vowel can be either long or short.

The phonology of the Natisone Valley dialect is similar to that of standard Slovene. Two major exceptions are the presence of diphthongs and the existence of palatal consonants. However, the dialect is not uniform, and differences exist between eastern and western microdialects.[11]

Consonants

The Natisone Valley dialect has 24 (in the east 25) distinct phonemes, in comparison to 22 in standard Slovene. This is mostly due to the fact that it still has palatal /ɲ/, /ʎ/, and /tɕ/, which depalatalized in standard Slovene, merging with the hard consonants.[14]

| Labial | Dental/ | Postalveolar | Dorsal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ||

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t | k | |

| voiced | b | d | (ɡ) | ||

| Affricate | voiceless | ts | tʃ | tɕ | |

| voiced | (dʒ) | ||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ʃ | x |

| voiced | z | ʒ | ɣ ~ ɦ | ||

| Approximant | central | ʋ | j | ||

| lateral | l | (ʎ) | |||

| Flap | ɾ | ||||

- Palatal /ʎ/ exists only in the eastern microdialects; in the western microdialects, it merged with /j/.

- The consonants /dʒ/ and /g/ are rare and only found in loanwords.

- Similarly to /l/ in standard Slovene, both /v/ and /l/ can undergo morphophonemic change into [u̯]; e.g., tràva 'grass' → tràunik 'grassland'.

- The consonant /tɕ/ has the allophone [ts] at the end of a word and [tsj] between vowels in the east. In the west, the difference between /tɕ/ and /tʃ/ is barely noticeable.

Vowels

The phonology of the Natisone Valley dialect is similar to that of standard Slovene, but it has a seven-vowel[15] (eastern microdialects eight-vowel)[16] system; two of those are diphthongs.

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u | |

| Mid | ɛ | (ə) | ɔ |

| Open | a | ||

| Diphthongs | ie~iɛ uo~uɔ | ||

Evolutionary perspective

The Natisone Valley dialect experienced lengthening of non-final vowels, and these became undistinguishable from their long counterparts, except for *ò. The vowel *ě̄ then turned into ie, and *ō into uo. Long *ə̄ turned into aː. Other long mid vowels (*ē, *ę̄, *ò, *ǭ) turned into eː and oː, respectively. The vowels *ī, *ū', and *ā remained unchanged. Syllabic *ł̥̄ turned into uː and syllabic r̥̄ turned into ar in the west and ər in the east.

Vowel reduction is almost non-existent; there is some akanye, e-akanye, and ikanye, but examples are rare. The only more common feature is loss of final -i, but even this is not the case in some more remote villages, such as Montemaggiore (Matajur) and Stermizza (Strmica). Short ə turned into either a or i in the west; in the east it remained ə only as a fill vowel. The cluster *ję- turned into i.

The palatal consonants remained palatal, but *ĺ turned into j in the west and *t’ turned into *č́. The consonant *g turned into ɣ and into x at the end of a word.[11]

The Natisone Valley dialect still has neuter gender in the singular, but it feminized in the plural. It still has the masculine and neuter o-stem declension, as well as the feminine a-stem and i-stem declension. There is also a masculine j-stem, as well as the remains of the feminine v-stem and neuter s-, t-, and n-stems. These are mostly limited to single words. However, the dialect has more archaic declension patterns that differ considerably from standard Slovene:[17]

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The infinitive has lost the final -i, but it has the same accent as the long infinitive.

There are many loanwords borrowed from Friulian and Italian, but not as much as in Torre Valley dialect. Words from Proto-Slavic received pretty close evolution to that of Standard Slovene, so both varieties are mutually intelligible.

| Natisone Valley | Standard Slovene | Meaning | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Writing | IPA | Writing | IPA | |

| kozá | [kɔˈza] | kóza | [ˈkɔ̀ːza] | 'goat' |

| kakùoša | [kaˈkúːɔʃa] | kokọ̑š | [kɔkóːʃ] | 'hen' |

| kandèla | [kanˈdɛ́ːla] | svẹ́ča | [ˈsvèːt͡ʃa] | 'candle' |

| golòb | [ɣɔˈlɔ́ːp] | golọ̑b | [gɔˈlɔ́ːp] | 'pigeon' |

| maglá | [maɣˈla] | meglȁ / mègla | [məgˈlá] / [mə̀gˈla] | 'fog' |

| ogìnj | [ɔˈɣiːɲ] | ógenj | [ˈɔ̀ːgən] | 'fire' |

| sér | [ˈsɛɾ] (west)

[ˈsəɾ] (east) |

sȉr | [ˈsɪ́ɾ] | 'cheese' |

| konác, kónc | [kɔˈnat͡s] (west)

[ˈkɔnt͡s] (east) |

kónec | [ˈkɔ̀ːnət͡s] | 'end' |

| ardèč | [aɾˈdɛ̀ːt͡ɕ] (west)

[əɾˈdɛ̀ːjt͡s] (east) |

rdȅč | [əɾˈdɛt͡ʃ] | 'red' |

| pandèjak | [panˈdɛ́ːjak] (west)

[panˈdɛ́ːʎk] (east) |

ponedẹ̑ljek | [pɔnɛˈdéːlɛk] | 'Monday' |

| ǧardìn | [d͡ʒaɾˈdíːn] | vȓt | [ˈvə́ɾt] | 'garden' |

| gjàndola | [ˈgjáːndɔla] | žlẹ́za | [ˈʒlèːza] | 'gland' |

The dialect's orthography is mainly based on western microdialects. It has 26 letters; 25 of them are the same as in the Slovene alphabet, and ⟨ǧ⟩ has been added for the phoneme /dʒ/, which is written ⟨dž⟩ in Standard Slovene.

Standard orthography, used in almost all situations, uses only the letters of the ISO basic Latin alphabet plus ⟨č⟩, ⟨š⟩, ⟨ž⟩, and ⟨ǧ⟩:[19]

| Letter | Phoneme | Example word | Pronunciation |

|---|---|---|---|

| A a | /aː/

/a/ /ă/ |

kajšan 'what kind'

zastonj 'for free' zavaržen 'thrown away' |

[ˈkaːjʃan] kàjšan

[zasˈtɔːɲ] zastònj [zaˈvăɾʒɛn] zavȧržen |

| B b | /b/ | bližat 'approach' | [ˈbliːʒat] blìžat |

| C c | /t͡s/ | lizavac 'sucker' | [liˈzaːvat͡s] lizàvac |

| Č č | /t͡ʃ/

/t͡ɕ/ |

lačan 'hungry'

ardeč 'red' |

[ˈlaːt͡ʃan] làčan

[aɾˈdɛːt͡ɕ] ardèč |

| D d | /d/ | nadluoga 'menace' | [naˈdluːɔɣa] nadlùoga |

| E e | /ɛː/

/ɛ/ /ɛ̆/ |

guarenje 'burning'

sparjet 'stuck' tešč 'having empty stomach' |

[ɣuaˈɾɛːnjɛ] guarènje

[spaɾˈjɛt] sparjèt [tɛ̆ʃt͡ʃ] tėšč |

| F f | /f/ | fruoštih 'zajtrk' | [ˈfɾuːɔʃtix] frùoštih |

| G g | /ɣ/

/ɡ/ |

oginj 'fire'

gjandola 'gland' |

[ɔˈɣiːɲ] ogìnj

[ˈgjaːndɔla] gjàndola |

| Ǧ ǧ | /d͡ʒ/ | ǧardin 'garden' | [d͡ʒaɾˈdíːn] ǧardìn |

| H h | /x/ | komicih 'rally' | [kɔˈmiːt͡six] komìcih |

| I i | /iː/

/i/ |

zmiešan 'mixed'

lizat 'to lick' |

[ˈzmiːɛʃan] zmìešan

[liˈzaːt] lizàt |

| J j | /j/ | uarnjen 'returned' | [ˈu̯ăɾnjɛn] uȧrnjen |

| K k | /k/ | kompit 'work' | [ˈkɔmpit] kómpit |

| L l | /l/ | kompleano 'birthday' | [kɔmplɛ.aːnɔ] kompleàno |

| M m | /m/ | popunoma 'completely' | [pɔˈpuːnɔma] popùnoma |

| N n | /n/ | skupen 'common' | [ˈskuːpɛn] skùpen |

| O o | /ɔː/

/ɔ/ /ɔ̆/ |

narobe 'wrong'

lenoba 'lazy person' trop 'herd' |

[naˈɾɔːbɛ] naròbe

[lɛnɔˈba] lenobá [ˈtɾɔ̆p] trȯp |

| P p | /p/ | pekoč 'spicy' | [pɛˈkɔːt͡ʃ] pekòč |

| R r | /r/ | saru 'raw' | [saˈɾuː] sarù |

| S s | /s/ | ser 'cheese' | [ˈsɛɾ] sér |

| Š š | /ʃ/ | saršen 'hornet' | [saɾˈʃɛn] saršén |

| T t | /t/ | prat 'to wash' | [ˈpɾaːt] pràt |

| U u | /uː/

/u/ /ŭ/ /u̯/ |

težkuo 'hard'

opudan 'at noon' saku 'falcon' debeu 'fat' |

[tɛʒˈkuːɔ] težkùo

[ɔpuˈdaːn] opudàn [saˈkŭ] saku̇ [dɛˈbɛu̯] debèu |

| V v | /ʋ/ | težava 'problem' | [tɛˈʒaːʋa] težàva |

| Z z | /z/ | zvit 'to bend' | [ˈzʋiːt] zvìt |

| Ž ž | /ʒ/ | odluožt 'to put down' | [ɔdˈluːɔʃt] odlùožt |

The orthography thus underdifferentiates several phonemic distinctions:

- Stress, vowel length, and tone are not distinguished, except with optional diacritics when it is necessary to distinguish between similar words with a different meaning.

- The consonant /g/ is not differentiated from its spirantized version, /ɣ/, and both are written as ⟨g⟩.

- The consonants /t͡ʃ/ and /t͡ɕ/ also are not differentiated, both being written as ⟨č⟩.

- The letter ⟨u⟩ is used to write syllabic /u/ as well as non-syllabic "false u" /u̯/.

The Natisone Valley dialect is unregulated, and thus a fair degree of variation is common in both pronunciation and writing. The eastern microdialects are completely unstandardized, like most other Slovene dialects. In contrast, the western microdialects have their own dictionary and grammar, written by Nino Špehonja in 2012.[3][20] The dictionary still allows many variations in writing, and consequently pronunciation. The main reason for different spellings is akanye, which is more common in some microdialects and less in others; e.g., the word for 'bonfire' can either be written as kries or krias.

- Smole, Vera. 1998. "Slovenska narečja." Enciklopedija Slovenije vol. 12, pp. 1–5. Ljubljana: Mladinska knjiga, p. 2.

- Šekli, Matej. 2004. "Jezik, knjižni jezik, pokrajinski oz. krajevni knjižni jezik: Genetskojezikoslovni in družbenostnojezikoslovni pristop k členjenju jezikovne stvarnosti (na primeru slovenščine)." In Erika Kržišnik (ed.), Aktualizacija jezikovnozvrstne teorije na slovenskem. Členitev jezikovne resničnosti. Ljubljana: Center za slovenistiko, pp. 41–58, p. 53.

- Špehonja, Nino (2012a). Vocabolario Italiano - Nediško (PDF) (in Italian). Poligrafiche San Marco. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- Logar (1996:11)

- "Karta slovenskih narečij z večjimi naselji" (PDF). Fran.si. Inštitut za slovenski jezik Frana Ramovša ZRC SAZU. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- Šekli (2018:327–328)

- Toporišič, Jože. 1992. Enciklopedija slovenskega jezika. Ljubljana: Cankarjeva založba, p. 25.

- Šekli (2018:326–328)

- Logar (1996:148)

- Logar (1996:148–150)

- Šekli (2018:326)

- Logar (1996:7–9)

- Logar (1996:254)

- Šekli (2007:409–410)

- Špehonja (2012b:45–58)

- Slovar slovenskega knjižnega jezika: SSKJ 2 (in Slovenian). Ljubljana: Znanstvenoraziskovalni center SAZU, Inštitut za slovenski jezik Frana Ramovša. 2015. pp. 40–41. ISBN 978-961-282-010-7. Archived from the original on 2022-03-18. Retrieved 2022-03-19.

- Špehonja (2012b:19–28)

- Logar, Tine (1996). Kenda-Jež, Karmen (ed.). Dialektološke in jezikovnozgodovinske razprave [Dialectological and etymological discussions] (in Slovenian). Ljubljana: Znanstvenoraziskovalni center SAZU, Inštitut za slovenski jezik Frana Ramovša. ISBN 961-6182-18-8.

- Šekli, Matej (2007). Fonološki opis govora vasi Jevšček pri Livku nadiškega narečja slovenščine (in Slovenian). Vol. 1–2. Ljubljana. pp. 409–427.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Šekli, Matej (2018). Legan Ravnikar, Andreja (ed.). Tipologija lingvogenez slovanskih jezikov (in Slovenian). Translated by Plotnikova, Anastasija. Ljubljana: Znanstvenoraziskovalni center SAZU. ISBN 978-961-05-0137-4.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Špehonja, Nino (2012b). Nediška gramatika (in Italian). Poligrafice San Marco.

- Zuljan Kumar, Danila (27–29 September 2018). Žele, Andreja; Šekli, Matej (eds.). Slovenski jezik v Nadiških dolinah (in Slovenian). Ljubljana: Zveza društev Slavistično društvo Slovenije. pp. 108–121. ISBN 978-961-6715-27-0. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: date and year (link)

- Nino Špehonja, Nediška gramatika, grammar of Natisone Valley dialect (in Italian).

- Nino Špehonja, Vocabolario Italiano-Nediško, Italian-Natisone Valley dialect dictionary (in Italian).