Nordic_Council

Nordic Council

Body for cooperation of Nordic countries

The Nordic Council is the official body for formal inter-parliamentary Nordic cooperation among the Nordic countries. Formed in 1952, it has 87 representatives from Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden as well as from the autonomous areas of the Faroe Islands, Greenland, and Åland. The representatives are members of parliament in their respective countries or areas and are elected by those parliaments. The Council holds ordinary sessions each year in October/November and usually one extra session per year with a specific theme.[3] The council's official languages are Danish, Finnish, Icelandic, Norwegian, and Swedish, though it uses only the mutually intelligible Scandinavian languages—Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish—as its working languages.[4] These three comprise the first language of around 80% of the region's population and are learned as a second or foreign language by the remaining 20%.[5]

Nordic Council

| |

|---|---|

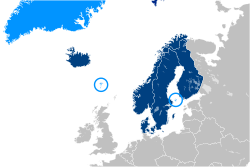

Member states shown in dark blue; and regions of member states shown in light blue. | |

| |

| Secretariat Headquarters | |

| Official languages | [1] |

| Type | Inter-parliamentary institution |

| Membership | 5 sovereign states 2 autonomous territories 1 autonomous region |

| Leaders | |

• President | |

• Vice-President | |

| Establishment | |

• Inauguration of the Nordic Council | 12 February 1953 |

| 1 July 1962 | |

• Inauguration of the Nordic Council of Ministers | July 1971 |

| Area | |

• Total | 6,187,000 km2 (2,389,000 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2019 estimate | 27.5 million |

• Density | 4.4/km2 (11.4/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2018 estimate |

• Total | US$1.6 trillion |

• Per capita | US$62,900 |

| GDP (nominal) | 2018 estimate |

• Total | US$1.7 trillion |

• Per capita | US$65,800 |

| Currency | |

In 1971, the Nordic Council of Ministers, an intergovernmental forum, was established to complement the council. The Council and the Council of Ministers are involved in various forms of cooperation with neighbouring areas in Northern Europe, including the German state of Schleswig-Holstein, the Benelux countries and the Baltic states.[6][7][8]

During World War II, Denmark and Norway were occupied by Germany; Finland was under assault by the Soviet Union; while Sweden, though neutral, still felt the war's effects. Following the war, the Nordic countries pursued the idea of a Scandinavian defence union to ensure their mutual defence. However, Finland, due to its Paasikivi-Kekkonen policy of neutrality and FCMA treaty with the USSR, could not participate.

It was proposed that the Nordic countries would unify their foreign policy and defence, remain neutral in the event of a conflict and not ally with NATO, which some were planning at the time. The United States, keen on getting access to bases in Scandinavia and believing the Nordic countries incapable of defending themselves, stated it would not ensure military support for Scandinavia if they did not join NATO. As Denmark and Norway sought US aid for their post-war reconstruction, the project collapsed, with Denmark, Norway and Iceland joining NATO.[9]

Further Nordic co-operation, such as an economic customs union, also failed. This led Danish Prime Minister Hans Hedtoft to propose, on 13 August 1951, a consultative interparliamentary body. This proposal was agreed by Denmark, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden during a meeting in Copenhagen on 15–16 March 1952.[10][11][12] The council's first session was held in the Danish Parliament on 13 February 1953 and it elected Hans Hedtoft as its president. When Finnish-Soviet relations thawed following the death of Joseph Stalin, Finland joined the council in 1955, following a voting in the Parliament of Finland on 28 October that year, effective from 23 December the same year.[13][14]

On 2 July 1954, the Nordic labour market was created and in 1958, building upon a 1952 passport-free travel area, the Nordic Passport Union was created. These two measures helped ensure Nordic citizens' free movement around the area. A Nordic Convention on Social Security was implemented in 1955. There were also plans for a single market but they were abandoned in 1959 shortly before Denmark, Norway, and Sweden joined the European Free Trade Area (EFTA). Finland became an associated member of EFTA in 1961 and Denmark and Norway applied to join the European Economic Community (EEC).[13]

This move towards the EEC led to desire for a formal Nordic treaty. The Helsinki Treaty outlined the workings of the council and came into force on 24 March 1962. Further advancements on Nordic cooperation were made in the following years: a Nordic School of Public Health, a Nordic Cultural Fund, and Nordic House in Reykjavík were created. Danish Prime Minister Hilmar Baunsgaard proposed full economic cooperation ("Nordek") in 1968. Nordek was agreed in 1970, but Finland then backtracked, stating that its ties with the Soviet Union meant it could not form close economic ties with potential members of the EEC (Denmark and Norway).[13] Nordek was then abandoned.

As a consequence, Denmark and Norway applied to join the EEC and the Nordic Council of Ministers was set up in 1971 to ensure continued Nordic cooperation.[15] In 1970 representatives of the Faroe Islands and Åland were allowed to take part in the Nordic Council as part of the Danish and Finnish delegations.[13] Norway turned down EEC membership in 1972 while Denmark acted as a bridge builder between the EEC and the Nordics.[16] Also in 1973, although it did not opt for full membership of the EEC, Finland negotiated a free trade treaty with the EEC that in practice removed customs duties from 1977 on, although there were transition periods up to 1985 for some products. Sweden did not apply due to its non-alliance policy, which was aimed at preserving neutrality. Greenland subsequently left the EEC and has since sought a more active role in circumpolar affairs.

In the 1970s, the Nordic Council founded the Nordic Industrial Fund, Nordtest and the Nordic Investment Bank. The council's remit was also expanded to include environmental protection and, in order to clean up the pollution in the Baltic Sea and the North Atlantic, a joint energy network was established. The Nordic Science Policy Council was set up in 1983[16] and, in 1984, representatives from Greenland were allowed to join the Danish delegation.[13]

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the Nordic Council began to cooperate more with the Baltic states and new Baltic Sea organisations. Sweden and Finland joined the European Union (EU), the EEC's successor, in 1995. Norway had also applied, but once again voted against membership.[17] However, Norway and Iceland did join the European Economic Area (EEA) which integrated them economically with the EU. The Nordic Passport Union was also subsumed into the EU's Schengen Area in 1996.

The Nordic Council became more outward-looking, to the Arctic, Baltic, Europe, and Canada. The Øresund Bridge linking Sweden and Denmark led to a large amount of cross-border travel, which in turn led to further efforts to reduce barriers.[17] However, the initially envisioned tasks and functions of the Nordic Council have become partially dormant due to the significant overlap with the EU and EEA. In 2008 Iceland began EU membership talks,[18] but decided to annul these in 2015.[19] Unlike the Benelux, there is no explicit provision in the Treaty on European Union that takes into account Nordic co-operation. However, the Treaties provide that international agreements concluded by the Member States before they become members of the Union remain valid, even if they are contrary to the provisions of Union law. However, each Member State must take all necessary measures to eliminate any discrepancies as quickly as possible. Nordic co-operation can therefore in practice only be designed to the extent that it complies with Union law.[20]

Council

The Nordic Council consists of 87 representatives, elected from its members' parliaments and reflecting the relative representation of the political parties in those parliaments. It holds its main session in the autumn, while a so-called "theme session" is arranged in the spring. Each of the national delegations has its own secretariat in the national parliament. The autonomous territories – Greenland, the Faroe Islands, and Åland – also have Nordic secretariats.[21]

The Council does not have any formal power on its own, but each government has to implement any decisions through its national legislature. With all countries being members of NATO, the Nordic Council has not been involved in any military cooperation.

Council of Ministers

The original Nordic Council concentrates on inter-parliamentary cooperation. The Nordic Council of Ministers, founded in 1971, is responsible for intergovernmental cooperation. Prime Ministers have ultimate responsibility but this is usually delegated to the Minister for Nordic Cooperation and the Nordic Committee for Co-operation, which coordinates the day-to-day work. The autonomous territories have the same representation as states.[22] The Nordic Council of Ministers has offices in the Baltic countries.[23]

Secretary General

Languages

The Nordic Council uses the three Continental Scandinavian languages (Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish) as its official working languages, while interpretation and translation service is arranged for Finnish and Icelandic (but never between the Scandinavian languages).[4] The council also publishes material in English for information purposes. The Council refers to Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish collectively as Scandinavian and considers them to be different forms of the same language forming a common language community.[24] Since 1987, under the Nordic Language Convention, citizens of the Nordic countries have the opportunity to use their native language when interacting with official bodies in other Nordic countries without being liable to any interpretation or translation costs. The Convention covers visits to hospitals, job centres, the police, and social security offices. The languages included are Danish, Finnish, Icelandic, Norwegian, and Swedish.[25]

On 31 October 2018, the council established it has five official languages, giving Finnish and Icelandic equal status with Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish from 1 January 2020 onward. While the working languages of the council's secretariat remain the three Scandinavian languages, the Council emphasised that the secretariat must include personnel with comprehensive understanding of Finnish and Icelandic as well. The then-President of the Council Michael Tetzschner thought the compromise good but also expressed concern over the change's expenses and hoped they would not increase so much that there would be pressure to switch over to using English.[26][27]

Language understanding

The Nordic Council and the Nordic Council of Ministers have a particular focus on strengthening the Nordic language community; the main focus of their work to promote language understanding in the Nordic countries is on children and young people's understanding of written and oral Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish, the three mutually intelligible Scandinavian languages.[28]

The Nordic Council and the Council of Ministers have their headquarters in Copenhagen and various installations in each separate country, as well as many offices in neighbouring countries. The headquarters are located at Ved Stranden No. 18, close to Slotsholmen.

The Nordic Council has five full members (which are sovereign states) and three associate members (which are self-governing regions of full member states).

| Member name | Symbols | Parliament | Membership | Membership status | Members | Represented since | EFTA/EU/EEA relation | NATO relation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arms | Flag | ||||||||

| Finland | Eduskunta (Riksdagen) | full | sovereign state | 20 | 1955 | EEA member |

|||

| Sweden | Riksdag | 1952 | |||||||

| Denmark | Folketing | ||||||||

| Norway | Storting | EEA member | |||||||

| Iceland | Alþingi | 7 | |||||||

| Greenland | Inatsisartut | associate | self-governing regions of Denmark | 2 (each) out of Denmark's 20 | 1984 | OCT | |||

| Faroe Islands | Løgting | 1970 | minimal | ||||||

| Åland | Lagting | self-governing region of Finland | 2 out of Finland's 20 | ||||||

List of members

As of December 2021[update][29]

In accordance with § 13 of the Rules of Procedure for the Nordic Council the Sámi Parliamentary Council is the only institution with observer status with the Nordic Council. In accordance with § 14, the Nordic Youth Council has the status of "guest" on a permanent basis, and the Presidium "may invite representatives of popularly elected bodies and other persons to a session and grant them speaking rights" as guests.[30] According to the council, "within the last couple of years, guests from other international and Nordic organisations have been able to take part in the debates at the Sessions. Visitors from the Baltic States and Northwest Russia are those who mostly take up this opportunity. Guests who have a connection to the theme under discussion are invited to the Theme Session."[31]

The Nordic Council of Ministers has established four Offices outside the Nordic Region: In Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and the German state of Schleswig-Holstein.[8] The offices form part of the secretariat of the Nordic Council of Ministers; according to the Council of Ministers their primary mission is to promote cooperation between the Nordic countries and the Baltic states and to promote the Nordic countries in cooperation with their embassies within the Baltic states.[32]

The Nordic Council and the Council of Ministers also define Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Russia as "Adjacent Areas" and has formal cooperation with them under the Adjacent Areas policies framework; in recent years the cooperation has focused increasingly on Russia.[7]

The Nordic Council had historically been a strong supporter of Baltic independence from the Soviet Union. During the move towards independence in the Baltic States in 1991, Denmark and Iceland pressed for the Observer Status in the Nordic Council for the then-nonsovereign Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. The move in 1991 was opposed by Norway and Finland. The move was heavily opposed by the Soviet Union, accusing the Nordic Council of getting involved in its internal affairs.[33] In the same year, the Nordic Council refused to give observer status for the three, at the time nonsovereign, Baltic states.[34]

While the Nordic Council rejected the Baltic states' application for formal observer status, the council nevertheless has extensive cooperation on different levels with all neighbouring countries, including the Baltic states and Germany, especially the state of Schleswig-Holstein. Representatives of Schleswig-Holstein were present as informal guests during a session for the first time in 2016. The state has historical ties to Denmark and cross-border cooperation with Denmark and has a Danish minority population.[35] As parliamentary representatives from Schleswig-Holstein, a member of the South Schleswig Voter Federation and a member of the Social Democrats with ties to the Danish minority were elected.[36]

The Sámi political structures long desired formal representation in the Nordic Council's structures, and were eventually granted observer status through the Sámi Parliamentary Council. In addition, representatives of the Sámi people are de facto included in activities touching upon their interests. In addition, the Faroe Islands have expressed their wishes for full membership in the Nordic Council instead of the current associate membership.[37]

Three of the members of the Nordic Council (Sweden, Denmark, and Finland, all EU member states), the Baltic Assembly, and the Benelux sought intensifying cooperation in the Digital Single Market, as well as discussing social matters, the Economic and Monetary Union of the European Union, the European migrant crisis and defense cooperation. Foreign relations in the wake of Russia's annexation of Crimea and the 2017 Turkish constitutional referendum were also on the agenda.[38]

Following the 2021 Scottish Parliament election, the Finnish member of Parliament Mikko Kärnä announced he would launch an initiative at the Nordic council to grant Scotland observer status.[39] Scotland's relationship with the Nordics has also been explored by Scottish journalist Anthony Heron, who would go on to interview Bertel Haarder on the topic.[40]

Some desire the Nordic Council's promotion of Nordic cooperation to go much further than at present. If the states of Iceland, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and Finland were to merge in such an integration as some desire, it would command a gross domestic product of US$1.60 trillion, making it the twelfth largest economy in the world, larger than that of Australia, Spain, Mexico, or South Korea. Gunnar Wetterberg, a Swedish historian and economist, wrote a book entered into the Nordic Council's year book that proposes the creation of a Nordic Federation from the Council in a few decades.[41]

Denmark portal

Denmark portal Finland portal

Finland portal Faroe Islands portal

Faroe Islands portal Iceland portal

Iceland portal Norway portal

Norway portal Sweden portal

Sweden portal Europe portal

Europe portal North America portal

North America portal

- Arctic Cooperation and Politics

- Baltic Assembly

- Baltic region

- Baltoscandia

- Benelux

- Council of the Baltic Sea States

- Council of Europe

- European Political Community

- European Parliament

- European Union Council

- Frugal Four

- Nordic-Baltic Eight

- Proposed United Kingdom Confederation

- Nordic Council Children and Young People's Literature Prize

- Nordic Council Environment Prize

- Nordic Council Film Prize

- Nordic Council Music Prize

- Nordic Council's Literature Prize

- Nordic Identity in Estonia

- Nordic Passport Union

- Nordic Summer University

- Nordic Youth Council

- West Nordic Council

- "The Nordic languages | Nordic cooperation". www.norden.org. Archived from the original on 5 September 2019. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- "information about the 2023 presidency on the council website". Archived from the original on 4 February 2023. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- "The Nordic Council". Nordic cooperation. Archived from the original on 6 July 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- "The Nordic languages". Nordic cooperation. Archived from the original on 5 September 2019. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- "Language". 6 August 2008. Archived from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- ERR (22 June 2017). "Ratas meets with Benelux, Nordic, Baltic leaders in the Hague". ERR. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- Tobias Etzold, "Nordic Institutionalized Cooperation in a Larger Regional Setting," in Johan Strang (ed.), Nordic Cooperation: A European Region in Transition, pp. 148ff, Routledge, 2015, ISBN 9781317626954

- Offices outside the Nordic Region Archived 17 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Nordic Council of Ministers.

- The plan for a Scandinavian Defence Union Archived 1 June 2019 at the Wayback Machine, European Navigator. Étienne Deschamps. Translated by the CVCE.

- Before 1952 Archived 30 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Nordic Council

- "70 years of the Nordic Council". Nordic Council. 11 March 2022. Archived from the original on 28 December 2022. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- "The history of the Nordic Council". Nordic Council. Archived from the original on 28 December 2022. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- 1953–1971 Finland joins in and the first Nordic rights are formulated. Archived 30 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Nordic Council

- Curt Olsson (1956). "Finlands lagstiftning 1955" (in Swedish). Svensk juristtidning. Archived from the original on 28 December 2022. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- The period up to 1971 Archived 20 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Nordic Council of Ministers

- 1972–1989 Archived 20 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Nordic Council of Ministers

- After 1989 Archived 20 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Nordic Council of Ministers

- "Further Icelandic support for EU membership | IceNews – Daily News". Icenews.is. 3 November 2008. Archived from the original on 14 February 2012. Retrieved 11 July 2009.

- "Iceland drops EU membership bid: 'interests better served outside' union". The Guardian. 12 March 2015. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- "About the Nordic Council". Archived from the original on 24 October 2014. Retrieved 8 November 2010.

- "The Nordic Council of Ministers". Archived from the original on 30 September 2017. Retrieved 8 November 2010.

- "Nordic Council of Ministers' Baltic offices | Nordic cooperation". www.norden.org. Archived from the original on 21 August 2021. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- Archived 28 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "Stärkt position för finskan och isländskan i Nordiska rådet" (in Swedish). 31 October 2018. Archived from the original on 2 November 2021. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- "Suomen ja islannin kielen asema vahvistuu Pohjoismaiden neuvostossa" (in Finnish). 31 October 2018. Archived from the original on 9 April 2022. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- "Language". Nordic co-operation. Archived from the original on 4 February 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- "Members of the Nordic Council | Nordic cooperation". www.norden.org. Archived from the original on 10 January 2022. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- Rules of Procedure for the Nordic Council. 2020. doi:10.6027/NO2020-011. ISBN 9789289364799. S2CID 242821185. Archived from the original on 2 March 2021. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- "About the Sessions of the Nordic Council". norden.org. Nordic Co-operation. Archived from the original on 26 February 2020. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- Planer och budget 2016. Nordic Council of Ministers. p. 71.

- Nichol, James P. (23 August 1995). Diplomacy in the Former Soviet Republics. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 113. ISBN 9780275951924.

- Smith, David (16 December 2013). Estonia: Independence and European Integration. Routledge. p. 157. ISBN 9781136452208.

- "Schleswig-Holstein for the first time uses its observer status in the Nordic Council". landtag.ltsh.de (in German). Landtag of Schleswig-Holstein. 1 November 2016. Archived from the original on 17 November 2016.

- "Election of observational members to the Nordic Council" (PDF). landtag.ltsh.de. Landtag of Schleswig-Holstein. 3 November 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- "The Faroe Islands apply for membership in the Nordic Council and Nordic Council of Ministers". norden.org. Nordic Co-operation. 18 October 2016. Archived from the original on 11 November 2022. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- "Ratas meets with Benelux, Nordic, Baltic leaders in the Hague". ERR.ee. 22 June 2017. Archived from the original on 26 July 2020. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- Richards, Xander (8 May 2021). "We'll try to get Scotland observer status on Nordic Council, Finnish MP tells SNP". thenational.scot. Newsquest Media Group Ltd. Archived from the original on 19 January 2023. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- Heron, Anthony (1 June 2022). "Former Nordic Council chief talks Scotland's global future". The National. Archived from the original on 14 August 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- Wetterberg, Gunnar (3 November 2010) Comment The United Nordic Federation Archived 14 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine, EU Observer