Political_group_of_the_European_Parliament

Political groups of the European Parliament

Groups of aligned legislators in European Parliament

The political groups of the European Parliament are the officially recognised parliamentary groups consisting of legislators of aligned ideologies in the European Parliament.

The European Parliament is unique among supranational assemblies in that its members (MEPs) organise themselves into ideological groups, rather than national cleavages.[1] Each political group is assumed to have a set of core principles, and political groups that cannot demonstrate this may be disbanded (see below).

A political group of the EP usually constitutes the formal parliamentary representation of one of the European political parties (Europarty), sometimes supplemented by members from other national political parties or independent politicians. In contrast to the European political parties, it is strictly forbidden for political groups to organise or finance the political campaign during the European elections since this is the exclusive responsibility of the parties.[2] But there are other incentives for MEPs to organise in parliamentary Groups: besides the political advantages of working together with like-minded colleagues, Groups have some procedural privileges within the Parliament (such as Group spokespersons speaking first in debates, Group leaders representing the Group in the Parliament's Conference of Presidents), and Groups receive a staff allocation and financial subsidies.[3] Majorities in the Parliament depend on how Groups vote and what deals are negotiated among them.

Although most of the political groups in the European Parliament correlate to a corresponding political party, there are cases where members from two political parties come together in a shared political group: for example, the European Free Alliance (half a dozen MEPs in the ninth Parliament) and the European Green Party (over 50 MEPs in the ninth Parliament) have, since 1999, felt they are stronger by working together in the European Greens–European Free Alliance Group than they would have as stand-alone groups (especially for the EFA, which would not otherwise have enough members to constitute a group). The same is true of the Renew Europe Group, most of whose members are from the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Party, but also includes a dozen from the small European Democratic Party. Both have also had independents and MEPs from minor parties also join their Group.

For a Group to be formally recognised in the Parliament, it must fulfil the conditions laid down in the relevant European Parliament Rule of Procedure.[4] This lays down the minimum criteria a Group must meet to qualify as a Group. The numerical criteria are 23 MEPs (at 3.3 percent, a lower threshold than in most national parliaments) but they must come from at least one quarter of Member States (so currently at least seven). They must also share political affinity and submit a political declaration, setting out the purpose of the group, the values that it stands for and the main political objectives which its members intend to pursue together. The requirement of political affinity was put to the test in July 1999, when a varied group of non-attached members, ranging from the Italian Radicals to the French Front National, tried to create a new “Technical Group”, but Parliament decided that the new Group did not, by its own admission, meet the requirement for political affinity. This decision was challenged at the CJEU, which found in Parliament's favour.

Further questions were asked when MEPs attempted to create a far-right Group called "Identity, Tradition, Sovereignty" (ITS). This generated controversy and there were concerns about public funds going towards a far-right Group.[3] Attempts to block the formation of ITS were unsuccessful, but ITS were blocked from leading positions on committees, when members from other Groups declined to vote for their candidates, despite a previous tradition of sharing such posts among members from all Groups.[5]

These events spurred MEPs, mainly from the largest two groups, to approve a rise in the threshold for groups to its current levels, having previously been even lower. This was opposed by many MEPs, notably from smaller Groups but also from the Liberal Group, arguing that it would be detrimental to democracy, whilst supporters argued that the change made it harder for a small number of members, possibly on the extremes (including the far right), to claim public funds.[6]

Groups may be based around a single European political party (e.g. the European People's Party, the Party of European Socialists) or they can include more than one European party as well as national parties and independents[7] (e.g. the Liberal Group).

Each Group appoints a leader, referred to as a "president", "co-ordinator" or "chair". The chairs of each Group meet in the Conference of Presidents to decide what issues will be dealt with at the plenary session of the European Parliament. Groups can table motions for resolutions and table amendments to reports.

Composition of the current (9th) European Parliament

Positions

This section needs to be updated. (December 2018) |

Social

EUL/NGL and G/EFA were the most left-wing groups, UEN and EDD the most right-wing, and that was mirrored in their attitudes towards taxation, homosexual equality, abortion, euthanasia and controlling migration into the EU. The groups fell into two distinct camps regarding further development of EU authority, with UEN and EDD definitely against and the rest broadly in favor. Opinion was wider on the CFSP, with different divisions on different issues. Unsurprisingly, G/EFA was far more in favor of Green issues compared to the other groups.

Attitude to EU tax

Table 1[19] of an April 2008 discussion paper[20] from the Centre for European Economic Research by Heinemann et al. analysed each Group's stance on a hypothetical generalised EU tax. The results for each Group are given in the adjacent diagram with the horizontal scale scaled so that −100% = totally against and 100% = totally for. The results are also given in the table below, rescaled so that 0% = totally against, 100% = totally for.

| Group | Attitude to a hypothetical EU tax | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|

| G/EFA | 97.5% | [19] | |

| PES | 85.1% | [19] | |

| ITS | 62.5% | [19] | |

| EUL/NGL | 55.0% | [19] | |

| Renew | 53.5% | [19] | |

| EPP-ED | 53.5% | [19] | |

| UEN | 34.8% | [19] | |

| IND/DEM | 0.0% | [19] | |

| NI | 0.0% | [19] | |

G/EFA and PES were in favor of such a tax, IND/DEM and the Independents were definitely against, the others had no clear position.

National media focus on the MEPs and national parties of their own member state, neglecting the group's activities and poorly understanding their structure or even existence. Transnational media coverage of the groups per se is limited to those organs such as the Parliament itself, or those news media (e.g. EUObserver or theParliament.com) that specialise in the Parliament. These organs cover the groups in detail but with little overarching analysis. So although such organs make it easy to find out how a group acted on a specific vote, they provide little information on the voting patterns of a specific group. As a result, the only bodies providing analysis of the voting patterns and Weltanschauung of the groups are academics.[citation needed] Academics analysing the European political groups include Simon Hix (London School of Economics and Political Science), Amie Kreppel University of Florida, Abdul Noury (Free University of Brussels), Gérard Roland, (University of California, Berkeley), Gail McElroy (Trinity College Dublin, Department of Political Science), Kenneth Benoit (Trinity College Dublin – Institute for International Integration Studies (IIIS)[21]), Friedrich Heinemann, Philipp Mohl, and Steffen Osterloh (University of Mannheim – Centre for European Economic Research[22]).

Groups cohesion

Cohesion is the term used to define whether a Group is united or divided amongst itself. Figure 1[23] of a 2002 paper from European Integration online Papers (EIoP) by Thorsten Faas analysed the Groups as they stood in 2002. The results for each Group are given in the adjacent diagram with the horizontal scale scaled so that 0% = totally split, 100% = totally united. The results are also given in the table below.

| Group | Cohesion | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|

| PES | approx 90% | [23] | |

| ELDR | approx 90% | [23] | |

| G/EFA | approx 90% | [23] | |

| EPP-ED | approx 80% | [23] | |

| UEN | approx 70% | [23] | |

| EUL/NGL | approx 65% | [23] | |

| TGI | approx 50% | [23] | |

| NI | approx 45% | [23] | |

| EDD | approx 35% | [23] | |

G/EFA, PES and ELDR were the most united groups, with EDD the most disunited.

Proportion of female MEPs

The March 2006 edition of "Social Europe: the journal of the European Left"[24] included a chapter called "Women and Social Democratic Politics" by Wendy Stokes. That chapter[25] gave the proportion of female MEPs in each Group in the European Parliament. The results for each Group are given in the adjacent diagram. The horizontal scale denotes gender balance (0% = totally male, 100% = totally female, but no Group has a female majority, so the scale stops at 50%). The results are also given in the table below.

| Group | Percentage female | Source | |

|---|---|---|---|

| G/EFA | 47.6% | [25] | |

| ALDE | 41% | [25] | |

| PES | 38% | [25] | |

| EUL/NGL | 29% | [25] | |

| EPP-ED | 23% | [25] | |

| UEN | 16.8% | [25] | |

| IND/DEM | 9% | [25] | |

G/EFA, PES and ALDE were the most balanced groups in terms of gender, with IND/DEM the most unbalanced.

Party relations

The Parliament does not form a government in the traditional sense and its politics have developed over consensual rather than adversarial lines as a form of consociationalism.[26] No single group has ever held a majority in Parliament.[27] Historically, the two largest parliamentary formations have been the EPP Group and the PES Group, which are affiliated to their respective European political parties, the European People's Party (EPP) and the Party of European Socialists (PES). These two Groups have dominated the Parliament for much of its life, continuously holding between 50 and 70 per cent of the seats together. The PES were the largest single party grouping up to 1999, when they were overtaken by the centre-right EPP.[28][29]

In 1987 the Single European Act came into force and, under the new cooperation procedure, the Parliament needed to obtain large majorities to make the most impact. So the EPP and PES came to an agreement to co-operate in the Parliament.[30] This agreement became known as the "grand coalition" and, aside from a break in the fifth Parliament,[31] it has dominated the Parliament for much of its life, regardless of necessity. The grand coalition is visible in the agreement between the two Groups to divide the five-year term of the President of the European Parliament equally between them, with an EPP president for half the term and a PES president for the other half, regardless of the actual election result.[26]

Group cooperation

Table 3[32] of 21 August 2008 version of working paper by Hix and Noury[33] gave figures for the level of cooperation between each group (how many times they vote with a group, and how many times they vote against) for the Fifth and Sixth Parliaments. The results are given in the tables below, where 0% = never votes with, 100% = always votes with.

| Group | Number of times voted with (%) | Sources | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EUL/NGL | G/EFA | PES | ALDE | EPP-ED | UEN | IND/DEM | NI | |||

| EUL/NGL | n/a | 75.4 | 62.0 | 48.0 | 39.6 | 42.2 | 45.5 | 48.6 | [32] | |

| G/EFA | 75.4 | n/a | 70.3 | 59.2 | 47.4 | 45.1 | 40.3 | 43.0 | [32] | |

| PES | 62.0 | 70.3 | n/a | 75.3 | 68.4 | 62.8 | 42.9 | 52.3 | [32] | |

| ALDE | 48.0 | 59.2 | 75.3 | n/a | 78.0 | 72.4 | 48.0 | 53.7 | [32] | |

| EPP-ED | 39.6 | 47.4 | 68.4 | 78.0 | n/a | 84.3 | 54.0 | 64.1 | [32] | |

| UEN | 42.2 | 45.1 | 62.8 | 72.4 | 84.3 | n/a | 56.8 | 64.7 | [32] | |

| IND/DEM | 45.5 | 40.3 | 42.9 | 48.0 | 54.0 | 56.8 | n/a | 68.1 | [32] | |

| NI | 48.6 | 43.0 | 52.3 | 53.7 | 64.1 | 64.7 | 68.1 | n/a | [32] | |

| Group | Number of times voted with (%) | Sources | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EUL/NGL | G/EFA | PES | ELDR | EPP-ED | UEN | EDD | NI | |||

| EUL/NGL | n/a | 79.3 | 69.1 | 55.4 | 42.4 | 45.9 | 59.2 | 52.4 | [32] | |

| G/EFA | 79.3 | n/a | 72.0 | 62.3 | 47.1 | 45.2 | 55.5 | 51.0 | [32] | |

| PES | 69.1 | 72.0 | n/a | 72.9 | 64.5 | 52.6 | 52.6 | 56.8 | [32] | |

| ELDR | 55.4 | 62.3 | 72.9 | n/a | 67.9 | 55.0 | 52.3 | 60.0 | [32] | |

| EPP-ED | 42.4 | 47.1 | 64.5 | 67.9 | n/a | 71.2 | 52.0 | 68.2 | [32] | |

| UEN | 45.9 | 45.2 | 52.6 | 55.0 | 71.2 | n/a | 62.6 | 73.8 | [32] | |

| EDD | 59.2 | 55.5 | 52.6 | 52.3 | 52.0 | 62.6 | n/a | 63.8 | [32] | |

| NI | 52.4 | 51.0 | 56.8 | 60.0 | 68.2 | 73.8 | 63.8 | n/a | [32] | |

EUL/NGL and G/EFA voted closely together, as did PES and ALDE, and EPP-ED and UEN. Surprisingly, given that PES and EPP-ED are partners in the Grand Coalition, they were not each other's closest allies, although they did vote with each other about two-thirds of the time. IND/DEM did not have close allies within the political groups, preferring instead to cooperate most closely with the Non-Inscrits.

Breaking coalitions

During the fifth term the ELDR Group were involved in a break in the grand coalition when they entered into an alliance with the European People's Party, to the exclusion of the Party of European Socialists.[31] This was reflected in the Presidency of the Parliament with the terms being shared between the EPP and the ELDR, rather than the EPP and PES as before.[34]

However ELDR intervention was not the only cause for a break in the grand coalition. There have been specific occasions where real left-right party politics have emerged, notably the resignation of the Santer Commission. When the initial allegations against the Commission Budget emerged, they were directed primarily against the PES Édith Cresson and Manuel Marín. PES supported the commission and saw the issue as an attempt by the EPP to discredit their party ahead of the 1999 elections. EPP disagreed. Whilst the Parliament was considering rejecting the Community budget, President Jacques Santer argued that a "No" vote would be tantamount to a vote of no confidence. PES leader Pauline Green MEP attempted a vote of confidence and the EPP put forward counter motions. During this period the two Groups adopted a government-opposition dynamic, with PES supporting the executive and EPP renouncing its previous coalition support and voting it down.[35]

In 2004 there was another notable break in the grand coalition. It occurred over the nomination of Rocco Buttiglione as European Commissioner for Justice, Freedom and Security. The EPP supported the appointment of Buttiglione, while the PES, who were also critics of the President-designate Jose Manuel Barroso, led the parties seeking Buttiglione's removal following his rejection (the first in EU history) by a Parliamentary committee. Barroso initially stood by his team and offered only small concessions, which were rejected by the PES. The EPP demanded that if Buttiglione were to go, then a PES commissioner must also be sacrificed for balance.[36] In the end, Italy withdrew Buttiglione and put forward Franco Frattini instead. Frattini won the support of the PES and the Barroso Commission was finally approved, albeit behind schedule.[37] Politicisation such as the above has been increasing, with Simon Hix of the London School of Economics noting in 2007 that[38]

Our work also shows that politics in the European Parliament is becoming increasingly based around party and ideology. Voting is increasingly split along left-right lines, and the cohesion of the party groups has risen dramatically, particularly in the fourth and fifth parliaments. So there are likely to be policy implications here too.

The dynamical coalitions in the European Parliament show year to year changes.[39]

Group switching

Party group switching in the European Parliament is the phenomenon where parliamentarians individually or collectively switch from one party group to the other. The phenomenon of EP party group switching is a well-known contributor to the volatility of the EP party system and highlights the fluidity that characterizes the composition of European political groups. On average 9% of MEPs switch during legislative terms. Party group switching is a phenomenon that gained force especially in the legislatures during the 1990s, up to a maximum of 18% for the 1989–1994 term, with strong prevalence among representatives from France and Italy, though by no means limited to those two countries. There is a clear tendency of party group switches from the ideological extremes, both left and right, toward the center. Most switching takes place at the outset of legislative terms, with another peak around the half-term moment, when responsibilities rotate within the EP hierarchy.[40]

| |||||||

The political groups of the European Parliament have been around in one form or another since September 1952 and the first meeting of the Parliament's predecessor, the Common Assembly. The groups are coalitions of MEPs and the European parties and national parties that those MEPs belong to. The groups have coalesced into representations of the dominant schools of European political thought and are the primary actors in the Parliament.

The first three Groups were established in the earliest days of the Parliament. They were the "Socialist Group" (which eventually became the S&D group), the "Christian Democrat Group" (later EPP group) and the "Liberals and Allies Group" (later ALDE group).

As the Parliament developed, other Groups emerged. Gaullists from France founded the European Democratic Union Group.[42] When Conservatives from Denmark and the United Kingdom joined, they created the European Conservatives Group, which (after some name changes) eventually merged with the Group of the European People's Party.[43]

The 1979 first direct election established further groups and the establishment of European political parties such as the European People's Party.[44]

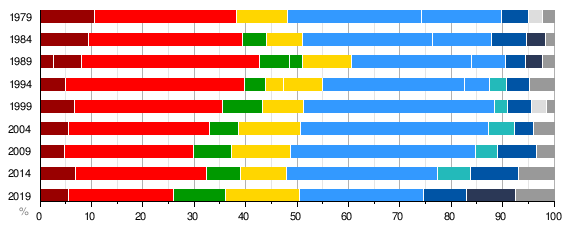

Compositions of past European Parliaments

5th European Parliament

| Group | Issue on which position was analysed | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left-Right | Tax | Deeper Europe | Federal Europe | Deregulation | Common Foreign and Security Policy | Fortress Europe (immigration) | Green issues | Homosexual equality, abortion, euthanasia | ||

| EUL/NGL | 18.0% | 75.5% | 52.5% | 46.0% | 20.0% | 39.0% | 30.5% | 65.5% | 78.5% | |

| G/EFA | 25.5% | 71.5% | 63.5% | 58.0% | 33.5% | 44.0% | 32.5% | 85.5% | 80.0% | |

| PES | 37.0% | 68.0% | 68.5% | 69.5% | 37.0% | 71.5% | 36.5% | 57.0% | 72.0% | |

| Renew | 59.0% | 34.5% | 62.5% | 68.5% | 71.0% | 68.5% | 37.0% | 45.5% | 78.0% | |

| EPP-ED | 63.0% | 33.0% | 63.0% | 63.0% | 67.5% | 70.0% | 60.0% | 39.5% | 30.5% | |

| UEN | 82.5% | 30.5% | 11.5% | 17.0% | 65.0% | 16.0% | 87.5% | 36.0% | 24.5% | |

| EDD | 85.5% | 29.5% | 5.5% | 5.5% | 73.0% | 7.5% | 87.5% | 35.5% | 24.5% | |

| Source | [45] | [46] | [46] | [46] | [45] | [46] | [45] | [46] | [46] | |

6th European Parliament

The mandate of previous European Parliament ran from 2004 and 2009. It was composed of the following political groups.

Table 3[47] of the 3 January 2008 version of a working paper[48] from the London School of Economics/Free University of Brussels by Hix and Noury considered the positions of the groups in the Sixth Parliament (2004–2009) by analysing their roll-call votes. The results for each group are shown in the adjacent diagram. The vertical scale is anti-pro Europe spectrum, (0% = extremely anti-Europe, 100% = extremely pro), and the horizontal scale is economic left-right spectrum, (0% = extremely economically left-wing, 100% = extremely economically right-wing). The results are also shown in the table below.

| Group | Left-right spectrum | Eurosceptic spectrum | Sources | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EUL/NGL | very left-wing | Eurosceptic | [47] | |

| PES | centre-left | very Europhile | [47] | |

| G/EFA | left-wing | Europhile | [47] | |

| Renew | centre | Europhile | [47] | |

| EPP-ED (EPP subgroup) | centre-right | Europhile | [47] | |

| EPP-ED (ED subgroup) | right-wing | Eurosceptic | [47] | |

| IND/DEM (reformist subgroup) | centre | very Eurosceptic | [47] | |

| IND/DEM (secessionist subgroup) | very right-wing | Secessionist | [47] | |

| UEN | centre-right | Eurosceptic | [47] | |

Two of the groups (EPP-ED and IND/DEM) were split. EPP-ED are split on Euroscepticism: the EPP subgroup ( ) were centre-right Europhiles, whereas the ED subgroup ( ) were right-wing Eurosceptics.

IND/DEM was also split along its subgroups: the reformist subgroup ( , bottom-center) voted as centrist Eurosceptics, and the secessionist subgroup ( , middle-right) voted as right-wing Euroneutrals. The reformist subgroup was able to pursue a reformist agenda via the Parliament. The secessionist subgroup was unable to pursue a secessionist agenda there (it's out of the Parliament's purview) and pursued a right-wing agenda instead. This resulted in the secessionist subgroup being less eurosceptic in terms of roll-call votes than other, non-eurosceptic parties. UKIP (the major component of the secessionist subgroup) was criticised for this seeming abandonment of its Eurosceptic core principles.[49]

Table 2[45][46] of a 2005 discussion paper[50] from the Institute for International Integration Studies by Gail McElroy and Kenneth Benoit analysed the group positions between April and June 2004, at the end of the Fifth Parliament and immediately before the 2004 elections. The results are given below, with 0% = extremely against, 100% = extremely for (except for the left-right spectrum, where 0% = extremely left-wing, 100% = extremely right-wing)

7th European Parliament

Eighth European Parliament

Major changes compared to the period 2004–2009 are:

- The formation of a new political group, the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR).[51] This conservative, Eurosceptic group is headed by 26 MEPs from the UK's Conservative Party.

- The Eurosceptic Independence/Democracy (IND/DEM) and Union for Europe of the Nations (UEN) groups suffered heavy losses in the election. On their own they no longer had enough MEPs to form a separate group. MEPs formerly from these groups formed the Europe of Freedom and Democracy (EFD) group on 1 July 2009.

- The centre-right European People's Party now formed its own political group in its entirety, as the former members of the European Democrats left the group to join the ECR.

- The political group of the Party of European Socialists renamed itself to the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats or Socialists and Democrats (S&D) to accommodate the Democratic Party of Italy.[52] The Democratic Party did not become member of the Party of European Socialists until February 2014.

Ninth European Parliament

History according to group

Some of the groups (such as the PES and S&D Group) have become homogeneous units coterminous with their European political party, some (such as IND/DEM) have not. But they are still coalitions, not parties in their own right, and do not issue manifestos of their own. It may therefore be difficult to discern how the groups intend to vote without first inspecting the party platforms of their constituent parties, and then with limited certainty.

Christian democrats and conservatives

In European politics, the centre-right is usually occupied by Christian democrats and conservatives. These two ideological strands have had a tangled relationship in the Parliament. The first Christian Democrat Group was founded in 1953[62] and stayed with that name for a quarter of a century. Meanwhile, outside the Parliament, local Christian-democratic parties were organising and eventually formed the pan-national political party called the "European People's Party" on 29 April 1976. Since all the Christian-democratic MEPs were members of this pan-European party, the Group's name was changed to indicate this: first to the "Christian-Democratic Group (Group of the European People's Party)"[44][63] on 14 March 1978,[44] then to "Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats)"[44][63][64] on 17 July 1979.[44] Meanwhile, on 16 January 1973,[43] the "European Conservative Group"[62] was formed by the British and Danish Conservative parties, which had recently joined the EEC. This group was renamed to the "European Democratic Group"[42][65] on 17 July 1979.[43] The EPP Group grew during the 1980s, with conservative parties such as New Democracy of Greece and the People's Party of Spain joining the Group. In contrast, the number of MEPs in the European Democratic Group fell over the same period and it eventually merged with the EPP Group on 1 May 1992.[43] This consolidation of the centre-right continued during the 1990s, with MEPs from the Italian centre-right party Forza Italia being admitted into the EPP Group on 15 June 1998,[66] after spending nearly a year (19 July 1994[66] to 6 July 1995[66]) in their own Group, self-referentially called "Forza Europa", and nearly three years (6 July 1995[66] to 15 June 1998[66]) in the national-conservative Group called "Union for Europe". But the Conservatives were growing restless and on 20 July 1999[62] the EPP Group was renamed[62] to the "Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) and European Democrats"[67] (EPP-ED) to identify the Conservative parties within the Group. The Group remained under that name until after the 2009 European elections, when it reverted to the title "Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats)" upon the exit of the European Democrats subgroup and the formation of the "European Conservatives and Reformists" group in June 2009.

| Group name |

English abbr. |

French abbr. |

Formal European Parliament name |

From | To |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christian Democratic Group | CD[62] | DC[44] | Christian Democratic Group[62][63] | 23 June 1953[44] | 14 March 1978[44] |

| Christian Democratic Group | CD[62] | DC[44] | Christian Democratic Group (Group of the European People's Party)[44][63] | 14 March 1978[44] | 17 July 1979[44] |

| European Conservatives | C[62] | n/a | European Conservative Group[62][65] | 16 January 1973[43] | 17 July 1979[43] |

| European Democrats | ED[42][62][68] | DE[43] | European Democratic Group[42][65] | 17 July 1979[43] | 1 May 1992[43] |

| European People's Party | EPP[68] | PPE[44] | Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats)[44][63][64] | 17 July 1979[44] | 1 May 1999[44] |

| Forza Europa | FE[42][68][69] | n/a | Forza Europa | 19 July 1994[66] | 6 July 1995[66] |

| European People's Party–European Democrats | EPP-ED[68] | PPE-DE[67] | Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) and European Democrats[67][70] | 20 July 1999[62] | 22 June 2009 |

| European People's Party | EPP | PPE | Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) | 22 June 2009 | present |

Social democrats

In western Europe, social-democratic parties have been the dominant centre-left force since the dawn of modern European cooperation. The Socialist Group was one of the first Groups to be founded when it was created on 23 June 1953[71] in the European Parliament's predecessor, the Common Assembly of the European Coal and Steel Community, and continued through the creation of the appointed Parliament in 1958 and the elected Parliament in 1979. Meanwhile, the national parties making up the Group were also organising themselves on a European level outside the Parliament, with the parties creating the "Confederation of Socialist Parties of the European Community" in 1974[62][72][73] and its successor, the "Party of European Socialists", in 1992.[72][73] As a result, the Group (which had kept its "Socialist Group" name all along) was renamed to the "Group of the Party of European Socialists" on 21 April 1993[71] and it became difficult to distinguish between the Party of European Socialists party and the political group. The Group reverted to (approximately) its former name of the "Socialist Group in the European Parliament".[67] on 20 July 2004[71] Despite all this, the Group was still universally referred to as "PES", notwithstanding the 2009 name change to the "Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats" to accommodate the Democratic Party of Italy.[74]

| Group name |

English abbr. |

French abbr. |

Formal European Parliament name |

From | To |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socialist Group | S[62] | n/a | Group of the Socialists[62] | 23 June 1953[71] | 1958[72] |

| Socialist Group | SOC[68] | n/a | Socialist Group[72][75] | 1958[72] | 21 April 1993[71] |

| Party of European Socialists | PES[68] | PSE[67] | "Group of the Party of European Socialists"[62][76] (until 20 July 2004)[71] "Socialist Group in the European Parliament"[67][77] (since 20 July 2004[71]) |

21 April 1993[71] | 23 June 2009 |

| Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats | S&D | S&D | Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament | 23 June 2009 | present |

Liberals and centrists

In European politics, liberalism tends to be associated with ideas inspired by classical and economic liberalism, which advocates limited government intervention in society. However, the Liberal Group contains diverse parties, including conservative-liberal, social-liberal and Nordic agrarian parties. It has previously been home to parties such as the minor French Gaullist party Union for the New Republic and the Social Democratic Party of Portugal, which were not explicitly liberal parties, but who were not aligned with either the Socialist or the Christian Democratic Groups. The Liberal Group was founded on 23 June 1953[78] under the name of the "Group of Liberals and Allies".[78] As the Parliament grew, it changed its name to the "Liberal and Democratic Group"[62][78] (1976[78]), then to the "Liberal and Democratic Reformist Group"[79] (13 December 1985[78]), then to the "Group of the European Liberal Democrat and Reform Party"[62][64][78] (19 July 1994[78]) before settling on the name of the "Group of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe"[78] on 20 July 2004,[78] when the Group was joined by the centrist parties that formed the European Democratic Party.

ELDR Group leader Graham Watson MEP denounced the grand coalition in 2007 and expressed a desire to ensure that the posts of Commission President, Council President, Parliament President and High Representative were not divided based on agreement between the two largest groups to the exclusion of third parties.[80]

Between 1994 and 1999 there was a separate "European Radical Alliance", which consisted of MEPs of the French Energie Radicale, the Italian Bonino List, and regionalists aligned with the European Free Alliance.[81]

The current name as of 2020 is "Renew Europe".

| Group name |

English abbr. |

French abbr. |

Formal European Parliament name |

From | To |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liberal Group | L[78] | n/a | Group of Liberals and Allies[78] | 23 June 1953[78] | 1976[78] |

| Liberal and Democratic Group | LD[78] | n/a | Liberal and Democratic Group[62][78][82] | 1976[78] | 13 December 1985[78] |

| Liberal and Democratic Reformist Group | LDR[42][78] | n/a | Liberal and Democratic Reformist Group[79] | 13 December 1985[78] | 19 July 1994[78] |

| European Liberal Democratic and Reform Party | ELDR[68][78] | n/a | Group of the European Liberal Democrat and Reform Party[62][64][78][83] | 19 July 1994[78] | 20 July 2004[78] |

| European Radical Alliance | ERA[68] | ARE[84] | Group of the European Radical Alliance[64][85] | 1994[42] | 1999[84] |

| Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe | ALDE[68] | ADLE[86] | Group of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe[78][87] | 20 July 2004[78] | June 2019 |

| Renew Europe | RE | RE | Renew Europe group | 20 June 2019 | present |

Eurosceptic conservatives

Parties from certain European countries have been unwilling to join the centre-right European People's Party Group. These parties generally have a liberal conservative but eurosceptic agenda. The first such Group was formed when the French Gaullists split from the Liberal Group on 21 January 1965[66] and created a new Group called the "European Democratic Union"[42][62] (not to be confused with the association of conservative and Christian-democratic parties founded in 1978 called the European Democrat Union nor the Conservative Group called the "European Democratic Group" founded in 1979). The Group was renamed on 16 January 1973[66] to the "Group of European Progressive Democrats"[88][89] when the Gaullists were joined by the Irish Fianna Fáil and Scottish National Party, and renamed itself again on 24 July 1984[66] to the "Group of the European Democratic Alliance".[42][89] The European Democratic Alliance joined with MEPs from Forza Italia to become the "Union for Europe"[64][90] on 6 July 1995,[66] but it did not last and the Forza Italia MEPs left on 15 June 1998 to join the EPP,[66] leaving Union for Europe to struggle on until it split on 20 July 1999.[66] The French Rally for the Republic members joined the EPP,[66] but Fianna Fáil and the Portuguese CDS–PP members joined a new group called the "Union for Europe of the Nations".[91] After the 2009 Parliament elections the Union for Europe of Nations was disbanded due to a lack of members, with the remaining members splitting into factions, with some joining with the remaining members of Independence/Democracy to form Europe of Freedom and Democracy, a new Eurosceptic group, and the remaining members joining with the former members of the European Democrat subgroup of the EPP-ED to form the European Conservatives and Reformists.

| Group name |

English abbr. |

French abbr. |

Formal European Parliament name |

From | To |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| European Democratic Union[42][62] | n/a | UDE[66] | European Democratic Union Group[89] | 21 January 1965[66] | 16 January 1973[66] |

| European Progressive Democrats[42][62] | EPD[92] | DEP[66] | Group of European Progressive Democrats[88][89] | 16 January 1973[66] | 24 July 1984[66] |

| European Democratic Alliance[68] | EDA[42][68] | RDE[66] | Group of the European Democratic Alliance[42][89][90] | 24 July 1984[66] | 6 July 1995[66] |

| Union for Europe | UFE[68] | UPE[66] | "Group Union for Europe"[64][90] | 6 July 1995[66] | 20 July 1999[66] |

| Union for Europe of the Nations | UEN[42][68] | n/a | Union for Europe of the Nations Group[91] | 20 July 1999[66][93] | 11 June 2009 |

| European Conservatives and Reformists | ECR | CRE | European Conservatives and Reformists Group | 24 June 2009 | present |

Greens and regionalists

In European politics, there has been a coalition between the greens and the stateless nationalists or regionalists (who also support devolution). In 1984[84] Greens and regionalists gathered into the "Rainbow Group",[42] a coalition of Greens, regionalists and other parties of the left unaffiliated with any of the international organisations. In 1989,[42][84] the group split: the Greens went off to form the "Green Group", whilst the regionalists stayed in Rainbow. Rainbow collapsed in 1994[84] and its members joined the "European Radical Alliance" under the French Energie Radicale. The Greens and regionalists stayed separate until 1999,[62][84] when they reunited under the "Greens/European Free Alliance"[62][67] banner.

| Group name |

English abbr. |

French abbr. |

Formal European Parliament name |

From | To |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rainbow Group | RBW[68] | ARC[84] | Rainbow Group: Federation of the Green Alternative European Left, Agalev-Ecolo, the Danish People's Movement against Membership of the European Community and the European Free Alliance in the European Parliament[85][94] | 1984[84] | 1989[42][84] |

| Rainbow Group | RBW[68] | ARC[84] | Rainbow Group in the European Parliament[84][85] | 1989[42][84] | 1994[84] |

| The Green Group | G[68] | V[95] | The Green Group in the European Parliament[64][96] | 1989[42][62][84] | 1999[62][84] |

| The Greens–European Free Alliance | G/EFA,[68] | Verts/ALE[67] | Group of the Greens–European Free Alliance[62][67][97] | 1999[62] | present |

Communists and socialists

The first communist group in the European Parliament was the "Communist and Allies Group"[42] founded on 16 October 1973.[98] It stayed together until 25 July 1989[98] when it split into two groups, the "Left Unity" Group[42] with 14[42] members and the "Group of the European United Left"[98] (EUL) with 28[42] members. EUL collapsed in January 1993[99] after the Italian Communist Party became the Democratic Party of the Left and its MEPs joined the PES Group, leaving Left Unity as the only leftist group before the 1994 elections.[99] The name was resurrected immediately after the elections when the "Confederal Group of the European United Left"[98] was formed on 19 July 1994.[98] On 6 January 1995,[98] when parties from Sweden and Finland joined, the Group was further renamed to the "Confederal Group of the European United Left–Nordic Green Left" and it has stayed that way to the present.

| Group name |

English abbr. |

French abbr. |

Formal European Parliament name |

From | To |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communists and Allies | COM[68] | n/a | Communist and Allies Group[42][100] | 16 October 1973[98] | 25 July 1989[98] |

| European United Left | EUL[68] | GUE[42][62] | Group for the European United Left[101] | 25 July 1989[98] | January 1993[99] |

| Left Unity | LU[68] | CG[42][98] | Left Unity[42][102] | 25 July 1989[98] | 19 July 1994[98] |

| European United Left | EUL[68] | GUE[42][62] | Confederal Group of the European United Left[98][103] | 19 July 1994[98] | 6 January 1995[98] |

| The Left in the European Parliament | EUL/NGL[68] | GUE/NGL[62][67] | Confederal Group of the European United Left–Nordic Green Left[64][67][103] | 6 January 1995[98][103] | present |

Right-wing nationalists

In European politics, a grouping of nationalists has thus far found it difficult to cohere in a continuous Group. The first nationalist Group was founded by the French National Front and the Italian Social Movement in 1984[42][104] under the name of the "Group of the European Right",[42][104] and it lasted until 1989.[104][105] Its successor, the "Technical Group of the European Right",[104][106] existed from 1989[104] to 1994.[104] There was then a gap of thirteen years until "Identity, Tradition, Sovereignty"[107] was founded on 15 January 2007,[107] which lasted for nearly eleven months until it fell apart on 14 November 2007 due to in-fighting.[108][109]

A new radical right group was formed during the 8th parliament on 16 June 2015 under the name "Europe of Nations and Freedom".[110][111]

| Group name |

English abbr. |

French abbr. |

Formal European Parliament name |

From | To |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| European Right | ER[42][68] | n/a | Group of the European Right[42][104][112] | 24 July 1984[112] | 24 July 1989[112] |

| European Right | DR[106] | n/a | Technical Group of the European Right[104][106][112] | 25 July 1989[112] | 18 July 1994[112] |

| Identity, Tradition, Sovereignty | ITS[107] | n/a | Identity, Tradition and Sovereignty Group[112] | 15 January 2007[107] | 14 November 2007[108] |

| Europe of Nations and Freedom | ENF[113] | ENL | Europe of Nations and Freedom Group[113] | 16 June 2015[114] | 13 June 2019 |

| Identity and Democracy | ID | ID | Identity and democracy Group | 13 June 2019 | present |

Eurosceptics

The school of political thought that states that the competences of the European Union should be reduced or prevented from expanding further, is represented in the European Parliament by the eurosceptics. The first Eurosceptic group in the European Parliament was founded on 19 July 1994.[115] It was called the "European Nations Group"[115] and it lasted until 10 November 1996.[115] Its successor was the "Group of Independents for a Europe of Nations",[64][116] founded on 20 December 1996.[115] Following the 1999 European elections, the Group was reorganised into the "Group for a Europe of Democracies and Diversities"[62][67] on 20 July 1999,[115] and similarly reorganised after the 2004 election into the "Independence/Democracy Group"[117] on 20 July 2004.[115] The group's leaders were Nigel Farage (UKIP) and Kathy Sinnott (Independent, Ireland). After the 2009 European elections a significant proportion of the IND/DEM members joined the "Europe of Freedom and Democracy", which included parties formerly part of the Union for a Europe of Nations. The EFD group's leaders were Farage and Francesco Speroni of the Lega Nord (Italy). With significant changes in membership after the 2014 European elections, the group was re-formed as "Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy", led by Farage and David Borrelli (Five Star Movement, Italy).

| Group name |

English abbr. |

French abbr. |

Formal European Parliament name |

From | To |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Europe of Nations | EN[68] | EDN[95] | Europe of Nations Group (Coordination Group)[118] | 19 July 1994[115][118] | 10 November 1996[115][118] |

| Independents for a Europe of Nations | I-EN[116] | I-EDN[115] | Group of Independents for a Europe of Nations[64][116][118][119] | 20 December 1996[115] | 20 July 1999[115] |

| Europe of Democracies and Diversities | EDD[62][67] | n/a | Group for a Europe of Democracies and Diversities[62][67][119] | 20 July 1999[115] | 20 July 2004[115] |

| Independence/Democracy | IND/DEM[68] | n/a | Independence/Democracy Group[117][119] | 20 July 2004[115] | 11 June 2009 |

| Europe of Freedom and Democracy | EFD | ELD | Europe of Freedom and Democracy Group[120] | 1 July 2009 | 24 June 2014 |

| Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy | EFDD | ELDD | Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy Group | 24 June 2014 | 26 June 2019 |

Heterogeneous

A Group is assumed to have a set of core principles ("affinities" or "complexion") to which the full members are expected to adhere. This throws up an anomaly: Groups get money and seats on Committees which Independent members do not get, but the total number of Independent members may be greater than the members of the smaller Groups. In 1979, MEPs got round this by forming a technical group (formally called the "Group for the Technical Coordination and Defence of Independent Groups and Members",[121] or "CDI"[81] for short) as a coalition of parties ranging from centre-left to far-left, which were not aligned with any of the major international organizations.[122] CDI lasted until 1984.[84] On 20 July 1999,[123] another technical group was formed, (formally called the "Technical Group of Independent Members – mixed group"[124] or "TGI"[68][123] for short). Since it contained far-right MEPs and centre-left MEPs, it could not possibly be depicted as having a common outlook. The Committee on Constitutional Affairs ruled[125] that TGI did not have a coherent political complexion, Parliament upheld (412 to 56 with 36 abstentions) the ruling,[126] and TGI was thus disbanded on 13 September 1999,[126] the first Group to be forcibly dissolved. However, the ruling was appealed to the European Court of First Instance[126] and the Group was temporarily resurrected on 1 December 1999[127] until the Court came to a decision.[127] On 3 October 2001, president Fontaine announced that the Court of First Instance had declared against the appeal[128] and that the disbandment was back in effect from 2 October 2001, the date of the declaration.[129] TGI appeared on the list of Political Groups in the European Parliament for the last time on 4 October 2001.[130] Since then the requirement that Groups have a coherent political complexion has been enforced (as ITS later found out), and "mixed" Groups are not expected to appear again.

| Group name |

English abbr. |

French abbr. |

Formal European Parliament name |

From | To |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technical Group of Independents | n/a | CDI[81] | "Group for the Technical Coordination and Defence of Independent Groups and Members"[121] | 20 July 1979[123] | 24 July 1984[126] |

| Technical Group of Independents | TGI[68][123] | TDI[62][67] | "Technical Group of Independent Members – mixed group"[124] | 20 July 1999[123] | 4 October 2001[130] |

Independents

Independent MEPs that are not in a Group are categorised as "Non-Inscrits" (the French term is universally used, even in English translations). This non-Group has no Group privileges or funding, and is included here solely for completeness.

[1][42][43][44][62][63][64][65][66][67][68][69][70][71][72][73][75][76][77][78][79][81][82][83][84][85][86][87][88][89][90][91][92][93][94][95][96][97][98][99][100][101][102][103][104][105][106][107][108][112][115][116][117][118][119][121][123][124][125][126][127][128][129][130]

- Acting from 7 January 2020 for Oriol Junqueras who has been prevented from travelling to the European Parliament due to his detention by Spanish authorities following Catalonia's independence referendum

- Hines, Eric (2003). "The European Parliament and the Europeanization of Green Parties" (PDF). University of Iowa. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 May 2008. Retrieved 1 March 2008.

- "European political parties". European Parliament.

- Brunwasser, Matthew (14 January 2007). "Bulgaria and Romania bolster far right profile in EU Parliament". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 7 July 2007.

- "Rules of Procedure of the European Parliament". Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- "Far-Right Wing Group Sidelined in European Parliament". Deutsche Welle. 2 February 2007. Retrieved 7 July 2007.

- Mahony, Honor (9 July 2008). "New rules to make it harder for MEPs to form political to another groups". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 10 July 2008.

- "Party Politics in the EU" (PDF). civitas.org.uk. Retrieved 12 June 2007.

- "The political groups". The political groups.

- "2019 European election results". Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- "MEPs by Member State and political group". www.europarl.europa.eu. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- "EPP loves Weber but some party members doubt he is 'the one'". POLITICO. 12 June 2019.

- Baume, Maïa de La (18 June 2019). "Socialists choose Spain's Iratxe García as group leader". POLITICO.

- "EU Parliament: Liberal ALDE group rebrands as 'Renew Europe'". euronews. 12 June 2019.

- "Group structure: Presidency". Renew Europe. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- in the European Parliament, Greens-EFA group (12 October 2022). "Terry Reintke takes the reins as Greens/EFA president".

- Rankin, Jennifer (13 June 2019). "MEPs create biggest far-right group in European parliament" – via www.theguardian.com.

- Discussion Paper No.08-027 "Who's afraid of an EU tax and why? – Revenue system preferences in the European Parliament", by Friedrich Heinemann, Philipp Mohl and Steffen Osterloh, ZEW Mannheim, April 2008 original figure taken from "Table 1: General EU tax preference (Q1) – comparisons of means", figure converted from −4 to +4 scale to 0% to 100% scale

- "DP 08-027" (PDF). Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- IIIS (Email). "Institute for International Integration Studies (IIIS) : Trinity College Dublin, The University of Dublin, Ireland". Tcd.ie. Retrieved 17 June 2010.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 April 2009. Retrieved 22 November 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Social Europe: the journal of the european left", issue 4, March 2006 Archived 2009-04-24 at the Wayback Machine original figure taken from chapter "Women and Social Democratic Politics" by Wendy Stokes, Senior Lecturer in Politics, London Metropolitan University

- Settembri, Pierpaolo (2 February 2007). "Is the European Parliament competitive or consensual ... "and why bother"?" (PDF). Federal Trust. Retrieved 7 October 2007.

- Kreppel, Amie (2002). "The European Parliament and Supranational Party System" (PDF). Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 12 June 2007.

- "History". Socialist Group website. Archived from the original on 1 November 2007. Retrieved 11 November 2007.

- "EPP-ED Chronology – 1991–2000". EPP-ED Group website. Retrieved 7 November 2007.

- "EPP-ED Chronology – 1981–1990". EPP-ED Group website. Retrieved 7 November 2007.

- "Interview: Graham Watson, leader of group of Liberal Democrat MEPs". Euractiv. 15 June 2004. Archived from the original on 14 August 2007. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- "After Enlargement: Voting Patterns in the Sixth European Parliament", by Simon Hix and Abdul Noury, LSE/ULB, 21 August 2008 Archived 24 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine original figure taken from "Table 3. Party Competition and Coalition Patterns"

- Archived 24 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "European Parliament elects new president". BBC News. 20 July 1999. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- Ringer, Nils F. (February 2003). "The Santer Commission Resignation Crisis" (PDF). University of Pittsburgh. Retrieved 7 October 2007.

- Bowley, Graham (26 October 2004). "Socialists vow to oppose incoming team: Barroso optimistic on commission vote". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 23 November 2007.

- Bowley, Graham (17 November 2004). "SEU Parliament likely to accept commission: Barroso set to win with new team". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 23 November 2007.

- "Professor Farrell: "The EP is now one of the most powerful legislatures in the world"". European Parliament. 18 June 2007. Archived from the original on 18 January 2008. Retrieved 5 July 2007.

- Evans, A.M. and M. Vink (2012). Measuring Group Switching in the European Parliament: Methodology, Data and Trends (1979–2009). Análise Social, XLVII (202), 92–112. See also mcelroy, G. (2008), "Intra-Party politics at the trans-national level: Party switching in the European Parliament". In D. Giannetti and K. Benoit (eds.), Intra-Party Politics and Coalition Governments in Parliamentary Democracies, London, Routledge, pp. 205–226.

- "Groupe des Démocrates Européens DE". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Party Groups and Policy Positions in the European Parliament" by Gail McElroy and Kenneth Benoit, Trinity College, Dublin, 10 March 2005" original figure taken from "Table 2. Policy Positions of European Party Groups", figure converted from 0 to 20 scale to 0% to 100% scale

- "Party Groups and Policy Positions in the European Parliament" by Gail McElroy and Kenneth Benoit, Trinity College, Dublin, 10 March 2005 original figure taken from "Table 2. Policy Positions of European Party Groups", figure converted from 0 to 20 scale to 0% to 100% scale and subtracted from 100% to have scale start at "extremely against"

- "After Enlargement: Voting Patterns in the Sixth European Parliament", by Simon Hix and Abdul Noury, LSE/ULB, 3 January 2008 original figure estimated from "Figure 3. Spatial Map of EP6"

- "SSRN-Party Groups and Policy Positions in the European Parliament by Gail McElroy, Kenneth Benoit" (PDF). Papers.ssrn.com. 10 March 2005. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- "BBC NEWS – UK – UK Politics – Conservative MEPs form new group". 22 June 2009. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- Donatella M. Viola (2015). "Italy". In Donatella M. Viola (ed.). Routledge Handbook of European Elections. Routledge. p. 134. ISBN 978-1-317-50363-7.

- "Presidency | EPP Group in the European Parliament". European People's Party Group. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- "Our president & bureau". Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- "ALDE Group becomes Renew Europe | ALDE Party". www.aldeparty.eu. Archived from the original on 10 July 2019.

- "Movers and Shakers | 28 June 2019". The Parliament Magazine. 28 June 2019. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

- "Renew Europe Group Structure". Renew Europe Group. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- "Members". Greens–European Free Alliance. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- "About // ECR Group". European Conservatives and Reformists. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- "Left reconfirms leadership team for 2024 // GUE/NGL Group". European United Left–Nordic Green Left. 23 November 2021. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

- "Political Groups of the European Parliament". Archived from the original on 17 May 2011.

- "Directory – MEPs – European Parliament". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Directory – MEPs – European Parliament". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "La droite de la droite au Parlement européen". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Annual Accounts of Political Groups". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Background information : 15-11-96". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Directory – MEPs – European Parliament". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Groupe socialiste au Parlement européen". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "IISH – Archives". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Party of European Socialists". Archived from the original on 30 October 2007. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- European socialists change name to accommodate Italian lawmakers. Monsters and Critics (23 June 2009). Retrieved on 2016-01-22.

- "Directory – MEPs – European Parliament". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Directory – MEPs – European Parliament". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Directory – MEPs – European Parliament". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Alliance des Démocrates et des Libéraux pour l'Europe ADLE". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Directory – MEPs – European Parliament". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Speech by G. Watson to the ELDR Congress in Berlin". ELDR website. 26 October 2007. Retrieved 1 December 2007. [dead link]

- "Directory – MEPs – European Parliament". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Directory – MEPs – European Parliament". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Groupe Arc-en-Ciel". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Directory – MEPs – European Parliament". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Directory – MEPs – European Parliament". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- Judge, Anthony (1978). "Types of international organization: detailed overview". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Directory – MEPs – European Parliament". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Directory – MEPs – European Parliament". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Directory – MEPs – European Parliament". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- Lane, Jan-Erik; David McKay; Kenneth Newton (1997). Political Data Handbook: OECD Countries. Oxford University Press. p. 191. ISBN 0-19-828053-X.

- "Groupe Union pour l'Europe des Nations UEN". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Directory – MEPs – European Parliament". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Directory – MEPs – European Parliament". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Directory – MEPs – European Parliament". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Groupe confédéral de la Gauche Unitaire Européenne-Gauche Verte Nordique GUE-GVN". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "European Union: Power and Policy-Making" second edition, ISBN 0-415-22164-1 Published 2001 by Routledge, edited by Jeremy John Richardson, Chapter 6 "Parliaments and policy-making in the European Union", esp. page 125, "Table 6.2 Party Groups in the European Parliament, 1979–2000"

- "Directory – MEPs – European Parliament". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Directory – MEPs – European Parliament". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Directory – MEPs – European Parliament". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Directory – MEPs – European Parliament". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "BBC NEWS – Europe – Who's who in EU's new far-right group". 12 January 2007. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "European Consortium for Political Research" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "European Parliament press releases". European Parliament. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "European Parliament press releases". European Parliament. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- Janet Laible (2008). Separatism and Sovereignty in the New Europe. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-230-61700-1.

- "Far-right parties form group in EU parliament". 15 June 2015. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "France's National Front says forms group in European Parliament". 15 June 2015. Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Directory – MEPs – European Parliament". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Marine LE PEN". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Far right MEPs form EU parliamentary group". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Groupe Indépendance-Démocratie ID". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "BBC News – Europe – European parties and groups". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Directory – MEPs – European Parliament". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Directory – MEPs – European Parliament". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Members". Archived from the original on 1 May 2012. Retrieved 1 May 2012.

- "Directory – MEPs – European Parliament". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- On 17 July 1979, CDI consisted of 11 MEPs: specifically Maurits P.-A. Coppieters of the Flemish People's Union, Else Hammerich, Jens-Peter Bonde, Sven Skovmand, and Jørgen Bøgh of the Danish People's Movement against the EEC, the Irish independent MEP Neil Blaney, Luciana Castellina from the Italian Proletarian Unity Party, Mario Capanna from the Italian Proletarian Democracy, and Marco Pannella, Emma Bonino and Leonardo Sciascia of the Radical Party

- "The Week : 20-07-99(s)". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Directory – MEPs – European Parliament". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "News report : 28-07-99". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Daily Notebook: 14-09-99(1)". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Daily Notebook: 01-12-99(2)". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Daily Notebook – 03-10-2001". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Debates – Wednesday, 3 October 2001 – Announcement by the President". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- "Daily Notebook – 04-10-2001". Retrieved 27 May 2016.

- see how European Political Groups vote and how they form coalitions on various policy areas

- European Parliament political groups

- Lists of MEPs by political group

- The Party System of the European Parliament: Collusive or Competitive? (includes groups and how they evolved since 1952/3)

- The European Parliament and Supranational Party System Cambridge University Press 2002

- Party Groups and Policy Positions in the European Parliament

- Josep M. Colomer. "How Political Parties, Rather than Member-States, Are Building the European Union" (proof copy), (via Google Books) in Widening the European Union: The Politics of Institutional Change, ed. Bernard Steunenberg. London: Routledge, 2002, ISBN 0-415-26835-4.