Powhatans

Powhatan

Indigenous Algonquian tribes from Virginia, U.S.

The Powhatan people (/ˌpaʊhəˈtæn, ˈhætən/;[1]) are Native Americans who belong to member tribes of the Powhatan Confederacy, or Tsenacommacah. They are Algonquian peoples whose historic territories were in eastern Virginia.[2]

This article's lead section may be too long. (April 2024) |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 3,850[citation needed] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Eastern Virginia | |

| Languages | |

| Historically Powhatan, currently English | |

| Religion | |

| Indigenous religion, Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Pamlico, Nanticoke, Lenape, Massachusett, and other Algonquian peoples |

Their Powhatan language is an Eastern Algonquian language, also known as Virginia Algonquian. In 1607, an estimated 14,000 to 21,000 Powhatan people lived in eastern Virginia when English colonists established Jamestown.[3]

The term Powhatan is also a title among the Powhatan people. English colonial historians often used this meaning of the term.[4]

In the late 16th and early 17th centuries, a mamanatowick (paramount chief) named Wahunsenacawh forged a political confederacy by uniting 30 tributary tribes, whose territory included much of eastern Virginia. Their territory was called Tsenacommacah ("densely inhabited Land"). English colonists called Wahunsenacawh The Powhatan.[5][6] Each of the tribes within the confederacy was led by a weroance (leader, commander), all of whom paid tribute to the Powhatan.[4]

After Wahunsenacawh died in 1618, hostilities with colonists escalated under the chiefdom of his brother, Opchanacanough, who unsuccessfully tried to repel encroaching English colonists.[7] His 1622 and 1644 attacks against the invaders failed, and the English almost eliminated the confederacy. By 1646, the Powhatan Paramount Chiefdom had been decimated, not just by warfare but from the infectious diseases, such as measles and smallpox newly introduced to North America by Europeans. The Native Americans did not have any immunity to these, which had been endemic to Europe and Asia for centuries. At least 75 percent of the Powhatan people died from these diseases in the 17th century alone.[8]

By the mid-17th century, English colonist were desperate for labor to develop the land. Almost half of the European immigrants to Virginia arrived as indentured servants. As settlement continued, the colonists imported growing numbers of enslaved Africans for labor. By 1700, the colonies had about 6,000 enslaved Africans, one-twelfth of the population. Enslaved people would at times escape and join the surrounding Powhatan. Some white indentured servants were also known to have fled and joined the Indigenous peoples. African slaves and indentured European servants often worked and lived together, and while marriage was not always legal, some Native people lived, worked, and had children with them. After Bacon's Rebellion in 1676, the colony enslaved Indians for control. In 1691, the House of Burgesses abolished the enslavement of Native peoples; however, many Powhatans were held in servitude well into the 18th century.[9]

English and Powhatan people often married, with the best-known being Pocahontas and John Rolfe. Their son was Thomas Rolfe, who has more than an estimated 100,000 descendants today.[10] Many of the First Families of Virginia have both English and Virginia Algonquian ancestry.[2]

Virginia state-recognized eight Native tribes with ancestral ties to the Powhatan Confederation.[11] The Pamunkey and Mattaponi are the only two peoples who have retained reservation lands from the 17th century.[4]

Today many descendants of the Powhatan Confederacy are enrolled in six federally recognized tribes in Virginia.[12] They are:

The name "Powhatan" (also transcribed by Strachey as Paqwachowng), also spelled Powatan, is the name of the Native American village or town of Wahunsenacawh. The title Chief or King Powhatan, used by English colonists, is believed to have been derived from the name of this site. Although the specific site of his home village is unknown, in modern times the Powhatan Hill neighborhood in the East End portion of the modern-day city of Richmond, Virginia is thought by many to be in the general vicinity of the original village. Tree Hill Farm in Henrico County is also a possible site.

"Powhatan" was also the name used by the Natives to refer to the river where the town sat at the head of navigation. The English colonists chose to name it after their leader, King James I. The English colonists named many features in the early years of the Virginia Colony in honor of the king, as well as for his three children, Elizabeth, Henry, and Charles.

Although portions of Virginia's longest river upstream from Columbia were much later named for Queen Anne of Great Britain, in modern times, it is called the James River. It forms at the confluence of the Jackson and Cowpasture Rivers near the present-day town of Clifton Forge, flowing east to Hampton Roads. (The Rivanna River, a tributary of the James River, and Fluvanna County, were named after Queen Anne). The only water body in Virginia to retain a name related to the Powhatan people is Powhatan Creek, located in James City County near Williamsburg.

Powhatan County and its county seat at Powhatan, Virginia were honorific names established years later, in locations west of the area populated by the Powhatan peoples. The county was formed in March 1777.

Complex paramount chiefdom

Various tribes each held some individual powers locally, and each had a chief known as a weroance (male) or, more rarely, a weroansqua (female), meaning "commander".[13]

As early as the era of John Smith, the individual tribes of this grouping were recognized by English colonists as falling under the greater authority of the centralized power led by the chiefdom of Powhatan (c. 1545 – c. 1618), whose proper name was Wahunsenacawh or (in 17th century English spelling) Wahunsunacock.[2]

In 1607, when the first permanent English colonial settlement in North America was founded at Jamestown, he ruled primarily from Werowocomoco, which was located on the northern shore of the York River. This site of Werowocomoco was rediscovered in the early 21st century; it was central to the tribes of the Confederacy. The improvements discovered at the site during archaeological research have confirmed that Powhatan had a paramount chiefdom over the other tribes in the power hierarchy. Anthropologist Robert L. Carneiro in his The Chiefdom: Precursor of the State. The Transition to Statehood in the New World (1981), deeply explores the political structure of the chiefdom and confederacy.[citation needed]

Powhatan (and his several successors) ruled what is called a complex chiefdom, referred to by scholars as the Powhatan Paramount Chiefdom. Research work continues at Werowocomoco and elsewhere that deepens understanding of the Powhatan world.[citation needed]

Powhatan builds his chiefdom

Wahunsenacawh had inherited control over six tribes but dominated more than 30 by 1607 when the English settlers established their Virginia Colony at Jamestown. The original six tribes under Wahunsenacawh were: the Powhatan (proper), the Arrohateck, the Appamattuck, the Pamunkey, the Mattaponi, and the Chiskiack.

He added the Kecoughtan to his fold by 1598. Some other affiliated groups included the Rappahannock, Moraughtacund, Weyanoak, Paspahegh, Quiyoughcohannock, Warraskoyack, and Nansemond. Another closely related tribe of the same language group was the Chickahominy, but they managed to preserve their autonomy from the Powhatan Paramount Chiefdom. The Accawmacke, located on the Eastern Shore across the Chesapeake Bay, were nominally tributary to the Powhatan Chiefdom but enjoyed autonomy under their own Paramount Chief or "Emperor", Debedeavon (aka "The Laughing King"). Half a million Native Americans were living in the Allegheny Mountains around the year 1600. 30,000 of those 500,000 lived in the Chesapeake region under Powhatan’s rule, by 1677 only five percent of his population remained. The huge jump in deaths was caused by exposure and contact with Europeans.[14]

In his Notes on the State of Virginia (1781–82), Thomas Jefferson estimated that the Powhatan Confederacy occupied about 8,000 square miles (20,000 km2) of territory, with a population of about 8,000 people, of whom 2400 were warriors.[15] Later scholars estimated the total population of the paramountcy as 15,000.

English settlers in the land of the Powhatan

The Powhatan Confederacy was where English colonists established their first permanent settlement in North America. Conflicts began immediately between the Powhatan people and English colonists; the colonists fired shots as soon as they arrived (due to a bad experience they had with the Spanish before their arrival). Within two weeks of the arrival of English colonists at Jamestown, deaths had occurred.

The settlers had hoped for friendly relations and had planned to trade with the Virginia Indians for food. Captain Christopher Newport led the first colonial exploration party up the James River in 1607 when he met Parahunt, weroance of the Powhatan proper. English colonists initially mistook him for the paramount Powhatan (mamanatowick), his father Wahunsenacawh, who ruled the confederacy. Settlers coming into the region needed to befriend as many Native Americans as possible due to the unfamiliarity with the land. Not too long after settling down, they realized the huge potential for tobacco. To grow more and more tobacco, they had to impede on Native territory. There were immediate issues that result in 14 years of warfare.[16]

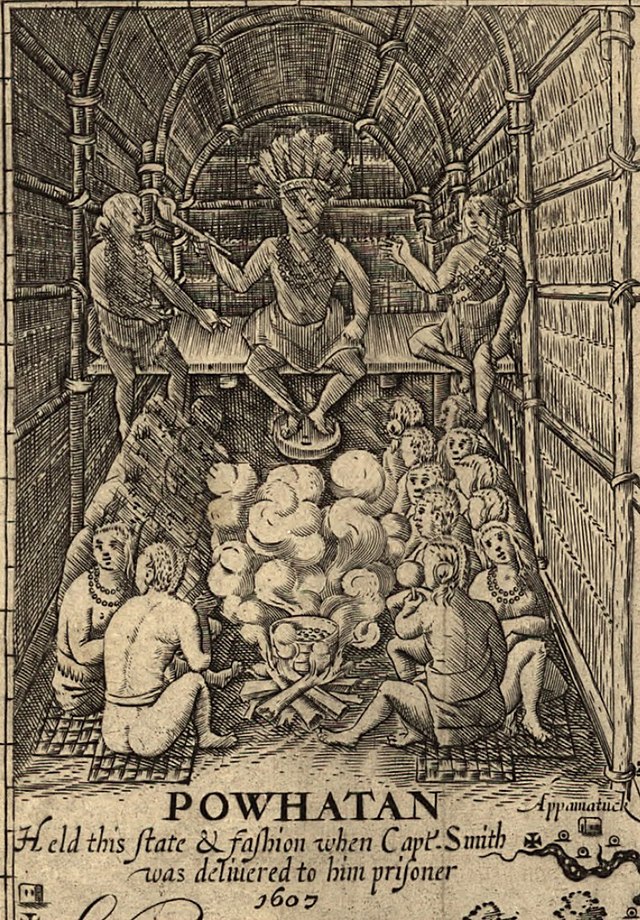

On a hunting and trade mission on the Chickahominy River in December 1607, Captain John Smith wrote that he fought a small battle between the Opechancanough, and during this battle, he tied his Indigenous guide to his body and used him as a human shield. Although Smith was wounded in the leg and also had many arrows in his clothing he was not deathly injured, soon after he was captured by the Opechancanough. After Smith was captured the Natives had him ready for execution until he gave them a compass which they saw as a sign of friendliness so they did not kill him, instead took him to a more popular chief, followed by a ceremony. Smith first was introduced to Powhatan's brother, which was a chief under Powhatan to run a smaller portion of the tribe. Later Smith was introduced to Powhatan himself.[17] Smith was captured by Opechancanough, the younger brother of Wahunsenacawh. Smith became the first English colonist to meet the paramount chief Powhatan. According to Smith's account, Pocahontas, Chief Powhatan's daughter, prevented her father from executing Smith.

Some researchers have asserted that a mock execution of Smith was a ritual intended to adopt Smith into the tribe, but other modern writers dispute this interpretation, noting that many of Smith's stories do not line up with the known facts. They point out that nothing is known of 17th-century Powhatan adoption ceremonies and that an execution ritual is different from known rites of passage. Other historians, such as Helen Rountree, have questioned whether there was any risk of execution. They note that Smith failed to mention it in his 1608 and 1612 accounts, and only added it to his 1624 memoir after Pocahontas had become famous.

In 1608, Captain Newport realized that Powhatan's friendship was crucial to the survival of the small Jamestown colony. In the summer of that year, he tried to "crown" the paramount Chief, with a ceremonial crown, to transform him into a "vassal".[18] They also gave Powhatan many European gifts, such as a pitcher, feather mattress, bed frame, and clothes. The coronation went badly because they asked Powhatan to kneel to receive the crown, which he refused to do. As a powerful leader, Powhatan followed two rules: "he who keeps his head higher than others ranks higher," and "he who puts other people in a vulnerable position, without altering his own stance, ranks higher." To finish the "coronation", several English colonists had to lean on Powhatan's shoulders to get him low enough to place the crown on his head, as he was a tall man. Afterward, the English colonists might have thought that Powhatan had submitted to King James, whereas Powhatan likely thought nothing of the sort.[19]

After John Smith became president of the colony, he sent a force under Captain Martin to occupy an island in Nansemond territory and drive the inhabitants away. At the same time, he sent another force with Francis West to build a fort at the James River Falls. He purchased the nearby fortified Powhatan village (present site of Richmond, Virginia) from Parahunt for some copper and an English colonist named Henry Spelman, who wrote a rare firsthand account of the Powhatan ways of life. Smith then renamed the village "Nonsuch", and tried to get West's men to live in it. Both these attempts at settling beyond Jamestown soon failed, due to Powhatan resistance. Smith left Virginia for England in October 1609, never to return, because of an injury sustained in a gunpowder accident. Soon afterward, English colonists established a second fort, Fort Algernon, in Kecoughtan territory.

Anglo-Powhatan Wars and treaties

In November 1609, Captain John Ratcliffe was invited to Orapakes, Powhatan's new capital. After he had sailed up the Pamunkey River to trade there, a fight broke out between the colonists and the Powhatan. All of the English colonists ashore were killed, including Ratcliffe, who was tortured by the women of the tribe. Those aboard the pinnace escaped and told the tale at Jamestown.

During that next year, the tribe attacked and killed many Jamestown residents. The residents fought back, but only killed twenty. However, the arrival at Jamestown of a new Governor, Thomas West, 3rd Baron De La Warr, (Lord Delaware) in June 1610 signaled the beginning of the First Anglo-Powhatan War. A brief period of peace came only after the capture of Pocahontas, her baptism, and her marriage to a tobacco planter, John Rolfe, in 1614. Within a few years, both Powhatan and Pocahontas were dead. Powhatan died in Virginia, but Pocahontas died in England. Meanwhile, the English settlers continued to encroach on Powhatan territory.

After Wahunsenacawh's death, his younger brother, Opitchapam, briefly became chief, followed by their younger brother Opechancanough. The Powhatans were frightened by the influx of immigrants, the expansion of new villages on traditional farming lands, the subsequent need to purchase food from the settlers, and the enforced placement of Indian youth in "colleges." In March 1622, they attacked the Jamestown plantations killing hundreds. The settlers quickly sought retaliation, killing hundreds of tribesmen and their families, burning fields, and spreading smallpox.[20] In 1644 the Powhatans again attacked English colonial settlements to force them from Powhatan territories, which was again met with strong reprisals from the colonists, ultimately resulting in the near destruction of the tribe. The Second Anglo–Powhatan War that followed the 1644 incident ended in 1646 after Royal Governor of Virginia William Berkeley's forces captured Opechancanough, thought to be between 90 and 100 years old. While a prisoner, Opechancanough was killed, shot in the back by a soldier assigned to guard him. He was succeeded as Weroance by Necotowance, and later by Totopotomoi and by his daughter Cockacoeske.

The Treaty of 1646 marked the effective dissolution of the United Confederacy, as white colonists were granted an exclusive enclave between the York and Blackwater Rivers. This physically separated the Nansemonds, Weyanokes, and Appomattox, who retreated southward, from the other Powhatan tribes then occupying the Middle Peninsula and Northern Neck. While the southern frontier demarcated in 1646 was respected for the remainder of the 17th century, the House of Burgesses lifted the northern one on September 1, 1649. Waves of new immigrants quickly flooded the peninsular region, then known as Chickacoan, and restricted the dwindling tribes to lesser tracts of land that became some of the earliest Indian reservations.

In 1665, the House of Burgesses passed stringent laws requiring the Powhatan to accept chiefs appointed by the governor. After the Treaty of Albany in 1684, the Powhatan Confederacy all but vanished.[citation needed]

Changing society and English expansion

Educational programs established through the creation of the Indian School at the College of William and Mary in 1691 were a driving force behind cultural change. The College provided Powhatan boys with skills considered to be of little use by their people, however, literacy was generally viewed as a benefit of this Western education, and Powhatan boys who had received education at William and Mary sent their sons to the school. The increasing marriage of Powhatans to non-Indigenous people in the 17th century is also believed to have contributed to cultural change.

The Powhatans had begun gambling, smoking tobacco, and consuming alcohol recreationally by the end of the 17th century.[21]

The Powhatan lived east of the Fall Line in Tidewater Virginia. They built their houses, called yehakins, by bending saplings and placing woven mats or bark over top of the saplings. They supported themselves primarily by growing crops, especially maize, but they also fished and hunted in the great forest in their area. Villages consisted of many related families organized in tribes led by a chief (weroance/werowance or weroansqua if female). They paid tribute to the paramount chief (mamanatowick), Powhatan.[5]

The region occupied by the Powhatan was bounded approximately by the Potomac River to the north, the Fall Line to the west, the Virginia-North Carolina border to the south, and the Atlantic Ocean to the east. Generally peaceful interactions with the Pamlicos and Chowanocs occurred along the southern boundary, while the western and northern boundaries were more contested. Conflicts occurred with Monacans and Mannahoacs along the western boundary and Massawomecks along the northern boundary.[21]

The Powhatans primarily used fires to heat their sleeping rooms. As a result, less bedding was needed, and bedding materials could be easily stored during daytime hours. Couples typically slept head to foot.[22]

According to research by the National Park Service, Powhatan "men were warriors and hunters, while women were gardeners and gatherers. English colonial accounts described the men, who ran and walked extensively through the woods in pursuit of enemies or game, as tall and lean and possessed of handsome physiques. The women were shorter, and strong because of the hours they spent tending crops, pounding corn into meals, gathering nuts, and performing other domestic chores. When the men undertook extended hunts, the women went ahead of them to construct hunting camps. The Powhatan domestic economy depended on the labor of both sexes."[23] Powhatan women would form work parties to accomplish tasks more efficiently. Women were also believed to serve as barbers, decorate homes, and produce decorative clothing. Overall, Powhatan women maintained a significant measure of autonomy in both their work lives and sexual lives.[22] After a long day, the Powhatan people would celebrate and burn off any last energy they had by dancing and singing. This also allowed them to release any tensions they had from working with others.[24]

All of Virginia's Native peoples practiced agriculture. They periodically moved their villages from site to site. Villagers cleared the fields by felling, girdling, or firing trees at the base and then using fire to reduce the slash and stumps. A village became unusable as soil productivity gradually declined and local fish and game were depleted. The inhabitants then moved on to allow the depleted area to revitalize, the soil to replenish, the foliage to grow, and the number of fish and game to increase. With every location change, the people used fire to clear new land. They left more cleared land behind. Native people also used fire to maintain extensive areas of open game habitat throughout the East, later called "barrens" by European colonists. The Powhatan also had rich fishing grounds. Bison had migrated to this area by the early 15th century.[25]

Powhatans made offerings and prayed at sunrise.[22] Although, they also prayed and made offerings to specific gods, who were believed to be in control of the harvest.[26] They used the land differently, and their religion was a Native one. Significantly, one of the major duties of Powhatan priests was controlling the weather.[27]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2023) |

The number of tribes listed and the number of warriors are based on estimates or reports which mostly go back to Captain John Smith (1580 - 1631) and William Strachey (1572 - 1621). Usually, only the number of the warriors of the individual tribes is known, the stem number will therefore be determined with a ratio of 1: 3, 1: 3,3, or the last 1: 4, and the studies of Christian Feest are decisive.[28] The last-mentioned figures refer to the first mention as well as the last mention of the respective tribes - e.g. 1585/1627 for the Chesapeake (Source: Handbook of North American Indians).

|

After Virginia passed stringent racial segregation laws in the early 20th century, and ultimately the Racial Integrity Act of 1924 which mandated every person who had any African heritage be deemed "black", Walter Plecker, the head of the vital Statistics office, directed all state and local registration offices to use only the terms "white" or "colored" to denote race on official documents. This eliminated all traceable records of Virginia Indians. All state documents, including birth certificates, death certificates, marriage licenses, tax forms, and land deeds, thus bear no record of Virginia Indians. Plecker oversaw the Vital Statistics office in the state for more than 30 years, beginning in the early 20th century, and took a personal interest in eliminating traces of Virginia Indians. Plecker surmised that no true Virginia Indians were remaining as years of intermarriage had "diluted the race". Over his years of service, he conducted a campaign to reclassify all biracial and multiracial individuals as Black, believing such persons were fraudulently attempting to claim their race to be Indian or white. The effect of his reclassification has been described by tribal members as "paper genocide".[47]

After the United States entered WWII many Powhatans volunteered to serve in the military. Powhatan men fought to be regarded separately from the Black community by the Selective Service. In 1954, Powhatans were given partial legal recognition by the General Assembly through a law stating that people with one-fourth or more Indian ancestry and one-sixteenth or less African ancestry were to be recognized as tribal Indians.[21]

State-recognized tribes

The Commonwealth of Virginia state-recognized 11 tribes, beginning with the Mattaponi and Pamunkey since its establishment.[48] In the 1980s, Virginia recognized six more tribes,[48] also descended from the Powhatan Confederacy. In 2010, Virginia recognized three more tribes;[48] one being the Patawomeck Indian Tribe of Virginia,[49] who identify as being descendants of the Patawomeck people who were loosely connected to the Powhatan Confederacy.

Of these state-recognized tribes who identify as being Powhatan descendants, all but the Mattaponi Indian Nation and the Patawomeck Indian Tribe of Virginia have since gained federal recognition.[12][50]

The Powhatan Renape Nation are a state-recognized tribe in New Jersey who identify as descendants of the Powhatan Confederacy.[51]

Federally recognized tribes

There are six federally recognized tribes of Powhatan people today, all based in Virginia.[12][50]

- Chickahominy Indian Tribe

- Chickahominy Indian Tribe–Eastern Division

- Nansemond Indian Nation

- Pamunkey Indian Tribe

- Rappahannock Tribe, Inc.

- Upper Mattaponi Tribe[12][50]

The Pamunkey Indian Tribe was the first to gain federal recognition in 2016.[12] Then the other six were recognized by Congress through the Thomasina E. Jordan Indian Tribes of Virginia Federal Recognition Act of 2017.[12]

Two of these tribes, the Mattaponi and Pamunkey, still retain their reservations from the 17th century and are located in King William County, Virginia.[4]

The tribes of the Powhatan Confederacy spoke mutually intelligible Algonquian languages. The most common was likely Powhatan. Its use became dormant due to the widespread deaths and social disruption suffered by the people. Much of the vocabulary bank is forgotten. Attempts have been made to reconstruct the vocabulary of the language using sources such as word lists provided by Smith and by the 17th-century writer William Strachey.

The Powhatan people are featured in MGM's live-action film Captain John Smith and Pocahontas (1953) and the Disney animated musical film Pocahontas (1995). They also appeared in the straight-to-video sequel Pocahontas II: Journey to a New World (1998). Some of the current members of Powhatan-descended tribes complained about the Disney film. Roy Crazy Horse of the Powhatan Renape Nation said the Disney movie "distorts history beyond recognition".[52]

An attempt at a more historically accurate representation was the drama The New World (2005), directed by Terrence Malick, which had actors speaking a reconstructed Powhatan language devised by the linguist Blair Rudes. The Powhatan people generally criticize the film for continuing the myth of a romance between Pocahontas and John Smith. Her actual husband was John Rolfe, whom she married on April 5, 1614.

More than an estimated 100,000 people today descend from Pocahontas' son Thomas Rolfe.[10] Notable descendants include Edith Bolling Galt Wilson, wife of Woodrow Wilson,[53] and actor Edward Norton.[54]

- "Writers' Guide" Archived 2012-02-24 at the Wayback Machine, Virginia Council on Indians, Commonwealth of Virginia, 2009

- Keith Egloff and Deborah Woodward. First People: The Early Indians of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia, 1992

- Sandra F. Waugaman and Danielle Moretti-Langholtz. We're Still Here: Contemporary Virginia Indians Tell Their Stories. Richmond: Palari Publishing, 2006 (revised edition).

- Wood, Karenne. The Virginia Indian Heritage Trail, 2007.

- Capossela, Julie Ann (February 2, 2006). "Jamestown from a Non-Western Perspective". NIAHD Journals. National Institute of American History & Democracy. Archived from the original on October 22, 2008.

- Horn, James (November 16, 2021). A Brave and Cunning Prince: The Great Chief Opechancanough and the War for America. Basic Books. ISBN 978-1-5416-0003-4.

- "1700: Virginia Native peoples succumb to smallpox". Native Voices. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved December 23, 2023.

- Rountree 1990

- Gruenke, Jonathan (March 22, 2019). "New project to identify descendants of Pocahontas underway". Daily Press. Virginia Gazette. Retrieved December 23, 2023.

- Hilleary, Cecily (January 31, 2018). "US Recognizes 6 Virginia Native American Tribes". Voice of America. Retrieved December 23, 2023.

- "Chronology of Powhatan Indian Activity", National Park Service

- Rabow-Edling, Susanna (2018). "The civic concept of the nation". Liberalism in Pre-Revolutionary Russia. Routledge. pp. 18–37. doi:10.4324/9781315149509-2. ISBN 978-1-315-14950-9. S2CID 240337595.

- "Encyclopedia". JAMA. 279 (17): 1409. May 6, 1998. doi:10.1001/jama.279.17.1409-jbk0506-6-1. ISSN 0098-7484.

- "Smith, Generall Historie of Virginia, 1624". history.hanover.edu. Retrieved December 10, 2019.

- Rountree, Helen C. and E. Randolph Turner III. Before and After Jamestown: Virginia's Powhatans and Their Predecessors. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2002.

- Rountree, Helen C. Pocahontas, Powhatan, Opechancanough: Three Indian Lives Changed by Jamestown. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2005

- Grizzard, Frank E. (2007). Jamestown Colony: A Political, Social, and Cultural History. Santa Barbara, CA: ABL-CLIO, Inc. pp. Introduction: l-li. ISBN 978-1-85109-637-4.

- Rountree, Helen C. (1996). Pocahontas's people: the Powhatan Indians of Virginia through four centuries. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-585-15425-2. OCLC 44957641.

- ""The Chesapeake Bay Region and its People in 1607"" (PDF). Retrieved November 15, 2018.

- Rountree, Helen C. (1998). "Powhatan Indian Women: The People Captain John Smith Barely Saw". Ethnohistory. 45 (1): 1–29. doi:10.2307/483170. JSTOR 483170.

- Brown, Hutch (Summer 2000). "Wildland Burning by American Indians in Virginia". Fire Management Today. 60 (3). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service: 30–33.

- "Gale General OneFile - Document - Pocahontas celebrates: a Powhatan harvest festival". go.gale.com. Retrieved March 12, 2020.

- Rountree, Helen C. (August 28, 1992). "Powhatan priests and English rectors: world views and congregations in conflict". The American Indian Quarterly. 16 (4): 485–. doi:10.2307/1185294. JSTOR 1185294. Retrieved August 28, 2020 – via Gale.

- "Seventeenth Century Virginia Algonquian Population Estimates (1973)". Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- "Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail - James River Basin - Indian Towns & Natural Resources They Relied On" (PDF). Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- "WE HAVE A STORY TO TELL - Native Peoples of Chesapeake Region" (PDF). Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- "VDOE :: Virginia's First People Past & Present - Nansemond". www.doe.virginia.gov. Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- "Chesapeake Bay - Native Americans - The Mariners' Museum". www.marinersmuseum.org. Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- The term Nottoway may derive from ″Nadawa″ or ″Nadowessioux″ (widely translated as "poisonous snake"), an Algonquian-language term which speakers used to refer to members of competing language families, specifically the Iroquoian- or Siouan-speaking tribes. Because the Algonquian occupied the coastal areas, they were the first tribes met by the English colonists, who often adopted the use of such Algonquian ethnonyms, names for other tribes, not realizing at first that these differed from the tribes' autonyms or names for themselves. The Nottoway called themselves in their tongue Nottaway (Dar-sun-ke) Cheroenhaka - "People at the Fork of the Stream" (because they lived in the region of the Nottaway, Blackwater River, and Chowan River - all Blackwater rivers), but the meaning of the name Cheroenhaka is uncertain and still disputed.

- "GNIS Detail - Pamunkey River". geonames.usgs.gov. Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- "Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail - York River Basin - Indian Towns & Natural Resources They Relied On" (PDF). Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- "VDOE :: Virginia's First People Past & Present - Pamunkey". www.doe.virginia.gov. Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- "Pampatike Farm - From Opechancanough to Col Thomas Carter". www.pampatike.org. Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- not to be confused with the small chieftain, also referred to as Mattapanient along the Patuxent River in northern Calvert and eastern Prince George's Counties of Maryland, which was under the Suzerainty of the Patuxent or the mighty Piscataway (Conoy)

- The information on the number of warriors (and hereby the population) for the additional tribes listed by Strachey – the Cantauncack,'Menapacunt, Pataunck, Ochahannauke, Kaposecock(e), Pamareke, Shamapa, Orapaks, Chepeco and the Paraconos – far exceed the usual populations for the Powhatan tribes. According to Feest Strachey's population numbers for the York and Mattaponi Rivers are to prefer over those of Smith (especially with regard to the mighty Mattaponie) – but are probably too high for the tribes along the Pamunkey River (the given 400 warriors or 1,300 tribal members for the Pamareke and Kaposecock(s) are questionable – since both tribes are often regarded as subgroups of the mighty Pamunkey – which according to Smith & Strachey could raise itself about 300 warriors or 1,000 Tribal members counted).

- "VDOE :: Virginia's First People Past & Present - Mattaponi". www.doe.virginia.gov. Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- "VDOE :: Virginia's First People Past & Present - Upper Mattaponi". www.doe.virginia.gov. Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- "Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail - Rappahannock River Basin - Indian Towns & Natural Resources They Relied On" (PDF). Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- "Christopher Steadman: The Powhatan Chiefdom: 1606, Old Dominion University, Model United Nations Society, 2015" (PDF). Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- "VDOE :: Virginia's First People Past & Present - Rappahannock". www.doe.virginia.gov. Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- Wolfe, Brendan (February 17, 2021). "Patawomeck Tribe". Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Humanities. Retrieved May 30, 2021.

- "Captain John Smith Chesapeake National Historic Trail – Lower Eastern Shore – Indian Towns & Natural Resources They Relied On" (PDF). Retrieved August 28, 2020.

- Fiske, Warren. "The Black-and-White World of Walter Ashby Plecker", The Virginian-Pilot, August 18, 2004

- "Virginia Indians". Secretary of the Commonwealth Kelly Gee. Retrieved December 23, 2023.

- "Patawomeck Indian Tribe of Virginia". Cause IQ. Retrieved December 23, 2023.

- Indian Affairs Bureau (January 12, 2023). "Indian Entities Recognized by and Eligible To Receive Services From the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs". Federal Register. 88: 2112–16. Retrieved December 23, 2023.

- Walsh, Jim (March 18, 2019). "State affirms status of Powhatan Renape, Ramapough Lenape tribes". Courier Post. Retrieved December 22, 2023.

- The Pocahontas Myth Archived July 5, 2013, at the Wayback Machine by Roy Crazy Horse, Powhatan Renape Nation website, accessed November 28, 2009

- Hatch, p. 42; Waldrup, p. 186; For a genealogy of Pocahontas' elite slave-holding settler descendants, see Wyndham Robertson, Pocahontas: Alias Matoaka, and Her Descendants through Her Marriage at Jamestown, Virginia, in April 1614, with John Rolph, Gentleman (J W Randolph & English, Richmond, VA, 1887).

- Halpert, Madeline (January 5, 2023). "How actor Edward Norton is related to Pocahontas". BBC News. Retrieved January 7, 2023.

- Sakas, Karliana. "The indigenous authorship of the narratives of the Spanish Jesuit mission of Ajacan (1570-1572)." EHumanista, vol. 19, 2011, p. 511+. Gale Academic Onefile, Accessed 14 Nov. 2019.

- Gleach, Frederic W. (1997) Powhatan's World and Colonial Virginia: A Conflict of Cultures. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Gleach, Frederic W. (2006) "Pocahontas: An Exercise in Mythmaking and Marketing", In New Perspectives on Native North America: Cultures, Histories, and Representations, ed. by Sergei A. Kan and Pauline Turner Strong, pp. 433–455. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Karen Kupperman, Settling With the Indians: The Meeting of English and Indian Cultures in America, 1580–1640, 1980

- A. Bryant Nichols Jr., Captain Christopher Newport: Admiral of Virginia, Sea Venture, 2007

- James Rice, Nature and History in the Potomac Country: From Hunter-Gatherers to the Age of Jefferson, 2009.

- Helen C. Rountree, Pocahontas's People: The Powhatan Indians of Virginia Through Four Centuries, 1990

![]() Media related to Powhatan at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Powhatan at Wikimedia Commons

- Chronology of Powhatan Indian Activity, National Park Service

- The Anglo-Powhatan Wars

- A Study of Virginia Indians and Jamestown: The First Century

- "American in 1607", National Geographic

- UNC Charlotte linguist Blair Rudes restores lost language, culture for 'The New World'

- How a linguist revived 'New World' language

- The Indigenous Maps and Mapping of North American Indians