Scots_language

Scots language

West Germanic language

Scots[note 1] is an Anglic language variety in the West Germanic language family, spoken in Scotland and parts of Ulster in the north of Ireland (where the local dialect is known as Ulster Scots).[3] Most commonly spoken in the Scottish Lowlands, Northern Isles, and northern Ulster, it is sometimes called Lowland Scots to distinguish it from Scottish Gaelic, the Goidelic Celtic language that was historically restricted to most of the Scottish Highlands, the Hebrides, and Galloway after the sixteenth century;[4] or Broad Scots to distinguish it from Scottish Standard English. Modern Scots is a sister language of Modern English, as the two diverged independently from the same source: Early Middle English (1100–1300).[5][6][7]

| Scots | |

|---|---|

| Lowland Scots Broad Scots | |

| (Braid) Scots Lallans Doric | |

| Pronunciation | [skɔts] |

| Native to | United Kingdom, Republic of Ireland |

| Region |

|

| Ethnicity | Scots |

Native speakers | 1,541,693 (2011)[1] |

Early forms | |

| Dialects | |

| Latin | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Scotland[2] |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | sco |

| ISO 639-3 | sco |

| Glottolog | scot1243 |

| ELP | Scots |

| Linguasphere | 52-ABA-aa (varieties: 52-ABA-aaa to -aav) |

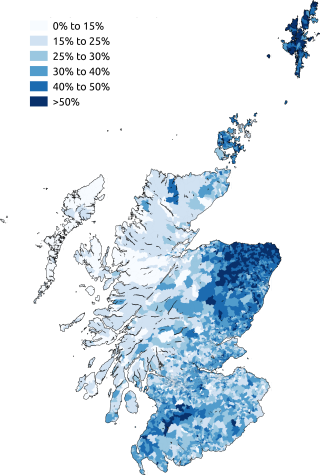

The proportion of respondents in the 2011 census in Scotland aged 3 and above who stated that they can speak Lowland Scots | |

The proportion of respondents in the 2011 census in Northern Ireland aged 3 and above who stated that they can speak Ulster Scots | |

Scots is recognised as an indigenous language of Scotland by the Scottish government,[8] a regional or minority language of Europe,[9] and a vulnerable language by UNESCO.[10][11] In the 2011 Scottish Census, over 1.5 million people in Scotland reported being able to speak Scots.[12]

Given that there are no universally accepted criteria for distinguishing a language from a dialect, scholars and other interested parties often disagree about the linguistic, historical and social status of Scots, particularly its relationship to English.[13] Although a number of paradigms for distinguishing between languages and dialects exist, they often render contradictory results. Broad Scots is at one end of a bipolar linguistic continuum, with Scottish Standard English at the other.[14] Scots is sometimes regarded as a variety of English, though it has its own distinct dialects;[13]: 894 other scholars treat Scots as a distinct Germanic language, in the way that Norwegian is closely linked to but distinct from Danish.[13]: 894

Native speakers sometimes refer to their vernacular as braid Scots (or "broad Scots" in English)[15] or use a dialect name such as the "Doric"[16] or the "Buchan Claik".[17] The old-fashioned Scotch, an English loan,[13]: 892 occurs occasionally, especially in Ulster.[18][19] The term Lallans, a variant of the Modern Scots word lawlands [ˈlo̜ːlən(d)z, ˈlɑːlənz],[20] is also used, though this is more often taken to mean the Lallans literary form.[21] Scots in Ireland is known in official circles as Ulster-Scots (Ulstèr-Scotch in revivalist Ulster-Scots) or "Ullans", a recent neologism merging Ulster and Lallans.[22]

Etymology

Scots is a contraction of Scottis, the Older Scots[15] and northern version of late Old English: Scottisc (modern English "Scottish"), which replaced the earlier i-mutated version Scyttisc.[23] Before the end of the fifteenth century, English speech in Scotland was known as "English" (written Ynglis or Inglis at the time), whereas "Scottish" (Scottis) referred to Gaelic.[24] By the beginning of the fifteenth century, the English language used in Scotland had arguably become a distinct language, albeit one lacking a name which clearly distinguished it from all the other English variants and dialects spoken in Britain. From 1495, the term Scottis was increasingly used to refer to the Lowland vernacular[13]: 894 and Erse, meaning "Irish", was used as a name for Gaelic. For example, towards the end of the fifteenth century, William Dunbar was using Erse to refer to Gaelic and, in the early sixteenth century, Gavin Douglas was using Scottis as a name for the Lowland vernacular.[25][26] The Gaelic of Scotland is now usually called Scottish Gaelic.

Northumbrian Old English had been established in what is now southeastern Scotland as far as the River Forth by the seventh century, as the region was part of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Northumbria.[30] Middle Irish was the language of the Scottish court, and the common use of Old English remained largely confined to this area until the thirteenth century. The succeeding variety of Northern Early Middle English spoken in southeastern Scotland is also known as Early Scots. It began to further diverge from the Middle English of Northumbria due to twelfth- and thirteenth-century immigration of Scandinavian-influenced Middle English–speakers from the North and Midlands of England.[30]: xliii Later influences on the development of Scots came from the Romance languages via ecclesiastical and legal Latin, Norman French,[30]: lxiii–lxv and later Parisian French, due to the Auld Alliance. Additionally, there were Dutch and Middle Low German influences due to trade with and immigration from the Low Countries.[30]: lxiii Scots also includes loan words in the legal and administrative fields resulting from contact with Middle Irish, and reflected in early medieval legal documents.[30]: lxi Contemporary Scottish Gaelic loans are mainly for geographical and cultural features, such as cèilidh, loch, whisky, glen and clan. Cumbric and Pictish, the medieval Brittonic languages of Northern England and Scotland, are the suspected source of a small number of Scots words, such as lum (derived from Cumbric) meaning "chimney".[31] From the thirteenth century, the Early Scots language spread further into Scotland via the burghs, which were proto-urban institutions first established by King David I. In fourteenth-century Scotland, the growth in prestige of Early Scots and the complementary decline of French made Scots the prestige dialect of most of eastern Scotland. By the sixteenth century, Middle Scots had established orthographic and literary norms largely independent of those developing in England.[32]

From 1610 to the 1690s during the Plantation of Ulster, some 200,000 Scots-speaking Lowlanders settled as colonists in Ulster in Ireland.[33][full citation needed] In the core areas of Scots settlement, Scots outnumbered English settlers by five or six to one.[34][full citation needed]

The name Modern Scots is used to describe the Scots language after 1700.[citation needed]

A seminal study of Scots was undertaken by JAH Murray and published as Dialect of the Southern Counties of Scotland.[35] Murray's results were given further publicity by being included in Alexander John Ellis's book On Early English Pronunciation, Part V alongside results from Orkney and Shetland, as well as the whole of England. Murray and Ellis differed slightly on the border between English and Scots dialects.[36]

Scots was studied alongside English and Scots Gaelic in the Linguistic Survey of Scotland at the University of Edinburgh, which began in 1949 and began to publish results in the 1970s.[37] Also beginning in the 1970s, the Atlas Linguarum Europae studied the Scots language used at 15 sites in Scotland, each with its own dialect.[38]

Language shift

From the mid-sixteenth century, written Scots was increasingly influenced by the developing Standard English of Southern England due to developments in royal and political interactions with England.[32]: 10 When William Flower, an English herald, spoke with Mary of Guise and her councillors in 1560, they first used the "Scottyshe toung". As he found this hard to understand, they switched into her native French.[39] King James VI, who in 1603 became James I of England, observed in his work Some Reulis and Cautelis to Be Observit and Eschewit in Scottis Poesie that "For albeit sindrie hes written of it in English, quhilk is lykest to our language..." (For though several have written of (the subject) in English, which is the language most similar to ours...). However, with the increasing influence and availability of books printed in England, most writing in Scotland came to be done in the English fashion.[32]: 11 In his first speech to the English Parliament in March 1603, King James VI and I declared, "Hath not God first united these two Kingdomes both in Language, Religion, and similitude of maners?".[40] Following James VI's move to London, the Protestant Church of Scotland adopted the 1611 Authorized King James Version of the Bible; subsequently, the Acts of Union 1707 led to Scotland joining England to form the Kingdom of Great Britain, having a single Parliament of Great Britain based in London. After the Union and the shift of political power to England, the use of Scots was discouraged by many in authority and education, as was the notion of "Scottishness" itself.[41] Many leading Scots of the period, such as David Hume, defined themselves as Northern British rather than Scottish.[41]: 2 They attempted to rid themselves of their Scots in a bid to establish standard English as the official language of the newly formed union. Nevertheless, Scots was still spoken across a wide range of domains until the end of the eighteenth century.[32]: 11 Frederick Pottle, the twentieth-century biographer of James Boswell (1740–1795), described James's view of the use of Scots by his father Alexander Boswell (1706–1782) [when?] in the eighteenth century while serving as a judge of the Supreme Courts of Scotland:

He scorned modern literature, spoke broad Scots from the bench, and even in writing took no pains to avoid the Scotticisms which most of his colleagues were coming to regard as vulgar.

However, others did scorn Scots, such as Scottish Enlightenment intellectuals David Hume and Adam Smith, who went to great lengths to get rid of every Scotticism from their writings.[42] Following such examples, many well-off Scots took to learning English through the activities of those such as Thomas Sheridan, who in 1761 gave a series of lectures on English elocution. Charging a guinea at a time (about £200 in today's money[43]), they were attended by over 300 men, and he was made a freeman of the City of Edinburgh. Following this, some of the city's intellectuals formed the Select Society for Promoting the Reading and Speaking of the English Language in Scotland. These eighteenth-century activities would lead to the creation of Scottish Standard English.[32]: 13 Scots remained the vernacular of many rural communities and the growing number of urban working-class Scots.[32]: 14

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the use of Scots as a literary language was revived by several prominent Scotsmen[citation needed] such as Robert Burns. Such writers established a new cross-dialect literary norm.

Scots terms were included in the English Dialect Dictionary, edited by Joseph Wright. Wright had great difficulty in recruiting volunteers from Scotland, as many refused to cooperate with a venture that regarded Scots as a dialect of English, and he obtained enough help only through the assistance from a Professor Shearer in Scotland.[44] Wright himself rejected the argument that Scots was a separate language, saying that this was a "quite modern mistake".[44]

During the first half of the twentieth century, knowledge of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century literary norms waned, and as of 2006[update], there is no institutionalised standard literary form.[45] By the 1940s, the Scottish Education Department's language policy was that Scots had no value: "it is not the language of 'educated' people anywhere, and could not be described as a suitable medium of education or culture".[46] Students reverted to Scots outside the classroom, but the reversion was not complete. What occurred, and has been occurring ever since, is a process of language attrition, whereby successive generations have adopted more and more features from Standard English. This process has accelerated rapidly since widespread access to mass media in English and increased population mobility became available after the Second World War.[32]: 15 It has recently taken on the nature of wholesale language shift, sometimes also termed language change, convergence or merger. By the end of the twentieth century, Scots was at an advanced stage of language death over much of Lowland Scotland.[47] Residual features of Scots are often regarded as slang.[48] A 2010 Scottish Government study of "public attitudes towards the Scots language" found that 64% of respondents (around 1,000 individuals in a representative sample of Scotland's adult population) "don't really think of Scots as a language", also finding "the most frequent speakers are least likely to agree that it is not a language (58%) and those never speaking Scots most likely to do so (72%)".[49]

Decline in status

Before the Treaty of Union 1707, when Scotland and England joined to form the Kingdom of Great Britain, there is ample evidence that Scots was widely held to be an independent sister language[50] forming a pluricentric diasystem with English.

German linguist Heinz Kloss considered Modern Scots a Halbsprache ('half language') in terms of an abstand and ausbau languages framework,[51] although today in Scotland most people's speech is somewhere on a continuum ranging from traditional broad Scots to Scottish Standard English. Many speakers are diglossic and may be able to code-switch along the continuum depending on the situation. Where on this continuum English-influenced Scots becomes Scots-influenced English is difficult to determine. Because standard English now generally has the role of a Dachsprache ('roofing language'), disputes often arise as to whether the varieties of Scots are dialects of Scottish English or constitute a separate language in their own right.[52][53]

The UK government now accepts Scots as a regional language and has recognised it as such under the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages.[54]

Notwithstanding the UK government's and the Scottish Executive's obligations under part II of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages, the Scottish Executive recognises and respects Scots (in all its forms) as a distinct language, and does not consider the use of Scots to be an indication of poor competence in English.

Evidence for its existence as a separate language lies in the extensive body of Scots literature, its independent – if somewhat fluid – orthographic conventions, and in its former use as the language of the original Parliament of Scotland.[55] Because Scotland retained distinct political, legal, and religious systems after the Union, many Scots terms passed into Scottish English.

During the 2010s, increased interest was expressed in the language.

Education

The status of the language was raised in Scottish schools,[56] with Scots being included in the new national school curriculum.[57] Previously in Scotland's schools there had been little education taking place through the medium of Scots, although it may have been covered superficially in English lessons, which could entail reading some Scots literature and observing the local dialect. Much of the material used was often Standard English disguised as Scots, which caused upset among proponents of Standard English and proponents of Scots alike.[58] One example of the educational establishment's approach to Scots is, "Write a poem in Scots. (It is important not to be worried about spelling in this – write as you hear the sounds in your head.)",[59] whereas guidelines for English require teaching pupils to be "writing fluently and legibly with accurate spelling and punctuation".[60]

A course in Scots language and culture delivered through the medium of Standard English and produced by the Open University (OU) in Scotland, the Open University's School of Languages and Applied Linguistics as well as Education Scotland became available online for the first time in December 2019.[61]

Government

In the 2011 Scottish census, a question on Scots language ability was featured[8] In 2022 a question regarding the Scots language was also featured.[62][63]

The Scottish government set its first Scots Language Policy in 2015, in which it pledged to support its preservation and encourage respect, recognition and use of Scots.[8] The Scottish Parliament website also offers some information on the language in Scots.[64]

Media

Serious use of the language for news, encyclopaedias, documentaries, etc., remains rare and usually reserved for niches where it is deemed acceptable, e.g. comedy, Burns Night, or representations of traditions and times gone by. However, since 2016 The National newspaper has regularly published some news articles in the language.[65] The 2010s also saw an increasing number of English books translated in Scots and becoming widely available, particularly those in popular children's fiction series such as The Gruffalo, Harry Potter, Diary of a Wimpy Kid, and several by Roald Dahl[66] and David Walliams.[67] In 2021, the music streaming service Spotify created a Scots language listing.[68]

In Scotland, Scots is spoken in the Scottish Lowlands, the Northern Isles, Caithness, Arran and Campbeltown. In Ulster, the northern province in Ireland, its area is usually defined through the works of Robert John Gregg to include the counties of Down, Antrim, Londonderry and Donegal (especially in East Donegal and Inishowen).[69] More recently, the Fintona-born linguist Warren Maguire has argued that some of the criteria that Gregg used as distinctive of Ulster-Scots are common in south-west Tyrone and were found in other sites across Northern Ireland investigated by the Linguistic Survey of Scotland.[70] Dialects of Scots include Insular Scots, Northern Scots, Central Scots, Southern Scots and Ulster Scots.

It has been difficult to determine the number of speakers of Scots via census, because many respondents might interpret the question "Do you speak Scots?" in different ways. Campaigners for Scots pressed for this question to be included in the 2001 UK National Census. The results from a 1996 trial before the Census, by the General Register Office for Scotland (GRO),[71] suggested that there were around 1.5 million speakers of Scots, with 30% of Scots responding "Yes" to the question "Can you speak the Scots language?", but only 17% responding "Aye" to the question "Can you speak Scots?".[citation needed] It was also found that older, working-class people were more likely to answer in the affirmative. The University of Aberdeen Scots Leid Quorum performed its own research in 1995, cautiously suggesting that there were 2.7 million speakers, though with clarification as to why these figures required context.[72]

The GRO questions, as freely acknowledged by those who set them, were not as detailed and systematic as the University of Aberdeen ones, and only included reared speakers (people raised speaking Scots), not those who had learned the language. Part of the difference resulted from the central question posed by surveys: "Do you speak Scots?". In the Aberdeen University study, the question was augmented with the further clause "... or a dialect of Scots such as Border etc.", which resulted in greater recognition from respondents. The GRO concluded that there simply was not enough linguistic self-awareness amongst the Scottish populace, with people still thinking of themselves as speaking badly pronounced, grammatically inferior English rather than Scots, for an accurate census to be taken. The GRO research concluded that "[a] more precise estimate of genuine Scots language ability would require a more in-depth interview survey and may involve asking various questions about the language used in different situations. Such an approach would be inappropriate for a Census." Thus, although it was acknowledged that the "inclusion of such a Census question would undoubtedly raise the profile of Scots", no question about Scots was, in the end, included in the 2001 Census.[52][73][74] The Scottish Government's Pupils in Scotland Census 2008[75] found that 306 pupils[clarification needed] spoke Scots as their main home language. A Scottish Government study in 2010 found that 85% of around 1000 respondents (being a representative sample of Scotland's adult population) claim to speak Scots to varying degrees.[49]

The 2011 UK census was the first to ask residents of Scotland about Scots. A campaign called Aye Can was set up to help individuals answer the question.[76][77] The specific wording used was "Which of these can you do? Tick all that apply" with options for "Understand", "Speak", "Read" and "Write" in three columns: English, Scottish Gaelic and Scots.[78] Of approximately 5.1 million respondents, about 1.2 million (24%) could speak, read and write Scots, 3.2 million (62%) had no skills in Scots and the remainder had some degree of skill, such as understanding Scots (0.27 million, 5.2%) or being able to speak it but not read or write it (0.18 million, 3.5%).[79] There were also small numbers of Scots speakers recorded in England and Wales on the 2011 Census, with the largest numbers being either in bordering areas (e.g. Carlisle) or in areas that had recruited large numbers of Scottish workers in the past (e.g. Corby or the former mining areas of Kent).[80]

Among the earliest Scots literature is John Barbour's Brus (fourteenth century), Wyntoun's Cronykil and Blind Harry's The Wallace (fifteenth century). From the fifteenth century, much literature based on the Royal Court in Edinburgh and the University of St Andrews was produced by writers such as Robert Henryson, William Dunbar, Gavin Douglas and David Lyndsay. The Complaynt of Scotland was an early printed work in Scots. The Eneados is a Middle Scots translation of Virgil's Aeneid, completed by Gavin Douglas in 1513.

After the seventeenth century, anglicisation increased. At the time, many of the oral ballads from the borders and the North East were written down. Writers of the period were Robert Sempill, Robert Sempill the younger, Francis Sempill, Lady Wardlaw and Lady Grizel Baillie.

In the eighteenth century, writers such as Allan Ramsay, Robert Burns, James Orr, Robert Fergusson and Walter Scott continued to use Scots – Burns's "Auld Lang Syne" is in Scots, for example. Scott introduced vernacular dialogue to his novels. Other well-known authors like Robert Louis Stevenson, William Alexander, George MacDonald, J. M. Barrie and other members of the Kailyard school like Ian Maclaren also wrote in Scots or used it in dialogue.

In the Victorian era popular Scottish newspapers regularly included articles and commentary in the vernacular, often of unprecedented proportions.[81]

In the early twentieth century, a renaissance in the use of Scots occurred, its most vocal figure being Hugh MacDiarmid whose benchmark poem "A Drunk Man Looks at the Thistle" (1926) did much to demonstrate the power of Scots as a modern idiom. Other contemporaries were Douglas Young, John Buchan, Sydney Goodsir Smith, Robert Garioch, Edith Anne Robertson and Robert McLellan. The revival extended to verse and other literature.

In 1955, three Ayrshire men – Sandy MacMillan, an English teacher at Ayr Academy; Thomas Limond, noted town chamberlain of Ayr; and A. L. "Ross" Taylor, rector of Cumnock Academy – collaborated to write Bairnsangs ("Child Songs"),[82] a collection of children's nursery rhymes and poems in Scots. The book contains a five-page glossary of contemporary Scots words and their pronunciations.

Alexander Gray's translations into Scots constitute the greater part of his work, and are the main basis for his reputation.

In 1983, William Laughton Lorimer's translation of the New Testament from the original Greek was published.

Scots is sometimes used in contemporary fiction, such as the Edinburgh dialect of Scots in Trainspotting by Irvine Welsh (later made into a motion picture of the same name).

But'n'Ben A-Go-Go by Matthew Fitt is a cyberpunk novel written entirely in what Wir Ain Leed[83] ("Our Own Language") calls "General Scots". Like all cyberpunk work, it contains imaginative neologisms.

The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam has been translated into Scots by Rab Wilson (published in 2004). Alexander Hutchison has translated the poetry of Catullus into Scots, and in the 1980s, Liz Lochhead produced a Scots translation of Tartuffe by Molière. J. K. Annand translated poetry and fiction from German and Medieval Latin into Scots.

The strip cartoons Oor Wullie and The Broons in the Sunday Post use some Scots. In 2018, Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stane, a Scots translation of the first Harry Potter book, Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone, was published by Matthew Fitt.

Vowels

The vowel system of Modern Scots:[84]

| Aitken | IPA | Common spellings |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | short /əi/ long /aɪ/ | i-e, y-e, ey |

| 2 | /i/ | ee, e-e, ie |

| 3 | /ei/[lower-alpha 1] | ei, ea |

| 4 | /e/ | a-e, #ae |

| 5 | /o/ | oa, o-e |

| 6 | /u/ | ou, oo, u-e |

| 7 | /ø/[lower-alpha 2][lower-alpha 3] | ui, eu[lower-alpha 3] |

| 8 | /eː/ | ai, #ay |

| 8a | /əi/[lower-alpha 4] | i-e, y-e, ey |

| 9 | /oe/ | oi, oy |

| 10 | /əi/[lower-alpha 4] | i-e, y-e, ey |

| 11 | /iː/ | #ee, #ie |

| 12 | /ɑː, ɔː/ | au, #aw |

| 13 | /ʌu/[lower-alpha 5] | ow, #owe |

| 14 | /ju/ | ew |

| 15 | /ɪ/ | i |

| 16 | /ɛ/ | e |

| 17 | /ɑ, a/ | a |

| 18 | /ɔ/[lower-alpha 6] | o |

| 19 | /ʌ/ | u |

- With the exception of North Northern dialects[85] this vowel has generally merged with vowels 2, 4 or 8.

Vowel length is usually conditioned by the Scottish vowel length rule.

Consonants

- Spelt ⟨ng⟩, always /ŋ/.[86]

- /t/ may be a glottal stop between vowels or word final.[86]: 501 In Ulster dentalised pronunciations may also occur, also for /d/.

- The cluster ⟨nch⟩ is usually realised /nʃ/[48]: 500 e.g. brainch ("branch"), dunch ("push"), etc.

- In Northern dialects, the clusters ⟨kn⟩ and ⟨gn⟩ may be realised as /kn/, /tn/ and /ɡn/[48]: 501 e.g. knap ("talk"), knee, knowe ("knoll"), etc.

- Spelt ⟨ch⟩, also ⟨gh⟩. Medial ⟨cht⟩ may be /ð/ in Northern dialects. loch ("fjord" or "lake"), nicht ("night"), dochter ("daughter"), dreich ("dreary"), etc. Similar to the German Nacht.[86]: 499 The spelling ⟨ch⟩ is realised /tʃ/ word initially or where it follows ⟨r⟩ e.g. airch ("arch"), mairch ("march"), etc.

- Spelt ⟨r⟩ and pronounced in all positions, i.e. rhotically. The phoneme /r/ is most commonly realised as an approximant [ɹ], although an alveolar tap [ɾ] is also common, especially among older speakers in rural areas. The realisation as a trill [r] is obsolete and only sporadically used for emphasis.[48]: 510–511

The orthography of Early Scots had become more or less standardised[87] by the middle to late sixteenth century.[88] After the Union of the Crowns in 1603, the Standard English of England came to have an increasing influence on the spelling of Scots[89] through the increasing influence and availability of books printed in England. After the Acts of Union in 1707 the emerging Scottish form of Standard English replaced Scots for most formal writing in Scotland.[32]: 11 The eighteenth-century Scots revival saw the introduction of a new literary language descended from the old court Scots, but with an orthography that had abandoned some of the more distinctive old Scots spellings[90] and adopted many standard English spellings. Despite the updated spelling, however, the rhymes make it clear that a Scots pronunciation was intended.[91] These writings also introduced what came to be known as the apologetic apostrophe,[91]: xiv generally occurring where a consonant exists in the Standard English cognate. This Written Scots drew not only on the vernacular, but also on the King James Bible, and was heavily influenced by the norms and conventions of Augustan English poetry.[13]: 168 Consequently, this written Scots looked very similar to contemporary Standard English, suggesting a somewhat modified version of that, rather than a distinct speech form with a phonological system which had been developing independently for many centuries.[92] This modern literary dialect, "Scots of the book" or Standard Scots,[93][94] once again gave Scots an orthography of its own, lacking neither "authority nor author".[95] This literary language used throughout Lowland Scotland and Ulster,[96] embodied by writers such as Allan Ramsay, Robert Fergusson, Robert Burns, Sir Walter Scott, Charles Murray, David Herbison, James Orr, James Hogg and William Laidlaw among others, is well described in the 1921 Manual of Modern Scots.[97]

Other authors developed dialect writing, preferring to represent their own speech in a more phonological manner rather than following the pan-dialect conventions of modern literary Scots,[91] especially for the northern[98] and insular dialects of Scots.

During the twentieth century, a number of proposals for spelling reform were presented. Commenting on this, John Corbett (2003: 260) writes that "devising a normative orthography for Scots has been one of the greatest linguistic hobbies of the past century". Most proposals entailed regularising the use of established eighteenth- and nineteenth-century conventions, in particular, the avoidance of the apologetic apostrophe, which represented letters that were perceived to be missing when compared to the corresponding English cognates but were never actually present in the Scots word.[99][100] For example, in the fourteenth century, Barbour spelt the Scots cognate of "taken" as tane. It is argued that, because there has been no k in the word for over 700 years, representing its omission with an apostrophe is of little value. The current spelling is usually taen.

Through the twentieth century, with the decline of spoken Scots and knowledge of the literary tradition, phonetic (often humorous) representations became more common.[citation needed]

Modern Scots follows the subject–verb–object sentence structure like Standard English. However, the word order Gie's it (Give us it) vs. "Give it to me" may be preferred.[13]: 897 The indefinite article a may be used before both consonants and vowels. The definite article the is used before the names of seasons, days of the week, many nouns, diseases, trades and occupations, sciences and academic subjects.[97]: 78 It is also often used in place of the indefinite article and instead of a possessive pronoun.[97]: 77 Scots includes some strong plurals such as ee/een ("eye/eyes"), cauf/caur ("calf/calves"), horse/horse ("horse/horses"), cou/kye ("cow/cows") and shae/shuin ("shoe/shoes") that survived from Old English into Modern Scots, but have become weak plurals in Standard Modern English – ox/oxen and child/children being exceptions.[97]: 79 [13]: 896 Nouns of measure and quantity remain unchanged in the plural.[13]: 896 [97]: 80 The relative pronoun is that for all persons and numbers, but may be elided.[13]: 896 [97]: 102 Modern Scots also has a third adjective/adverb this-that-yon/yonder (thon/thonder) indicating something at some distance.[13]: 896 Thir and thae are the plurals of this and that respectively. The present tense of verbs adheres to the Northern subject rule whereby verbs end in -s in all persons and numbers except when a single personal pronoun is next to the verb.[13]: 896 [97]: 112 Certain verbs are often used progressively[13]: 896 and verbs of motion may be dropped before an adverb or adverbial phrase of motion.[13]: 897 Many verbs have strong or irregular forms which are distinctive from Standard English.[13]: 896 [97]: 126 The regular past form of the weak or regular verbs is -it, -t or -ed, according to the preceding consonant or vowel.[13]: 896 [97]: 113 The present participle and gerund in are now usually /ən/[101] but may still be differentiated /ən/ and /in/ in Southern Scots,[102] and /ən/ and /ɪn/ in Northern Scots. The negative particle is na, sometimes spelled nae, e.g. canna ("can't"), daurna ("daren't"), michtna ("mightn't").[97]: 115

Adverbs usually take the same form as the verb root or adjective, especially after verbs. Examples include Haein a real guid day ("Having a really good day") and She's awfu fauchelt ("She's awfully tired").

From The Four Gospels in Braid Scots (William Wye Smith):

Noo the nativitie o' Jesus Christ was this gate: whan his mither Mary was mairry't till Joseph, 'or they cam thegither, she was fund wi' bairn o' the Holie Spirit.

Than her guidman, Joseph, bein an upricht man, and no desirin her name sud be i' the mooth o' the public, was ettlin to pit her awa' hidlins.

But as he had thir things in his mind, see! an Angel o' the Lord appear't to him by a dream, sayin, "Joseph, son o' Dauvid, binna feared to tak till ye yere wife, Mary; for that whilk is begotten in her is by the Holie Spirit.

"And she sall bring forth a son, and ye sal ca' his name Jesus; for he sal save his folk frae their sins."

Noo, a' this was dune, that it micht come to pass what was said by the Lord throwe the prophet,

"Tak tent! a maiden sal be wi' bairn, and sal bring forth a son; and they wull ca' his name Emmanuel," whilk is translatit, "God wi' us."

Sae Joseph, comin oot o' his sleep, did as the Angel had bidden him, and took till him his wife.

And leev'd in continence wi' her till she had brocht forth her firstborn son; and ca'd his name Jesus.— Matthew 1:18–21

From The New Testament in Scots (William Laughton Lorimer, 1885–1967)

This is the storie o the birth o Jesus Christ. His mither Mary wis trystit til Joseph, but afore they war mairriet she wis fund tae be wi bairn bi the Halie Spírit. Her husband Joseph, honest man, hed nae mind tae affront her afore the warld an wis for brakkin aff their tryst hidlinweys; an sae he wis een ettlin tae dae, whan an angel o the Lord kythed til him in a draim an said til him, "Joseph, son o Dauvit, be nane feared tae tak Mary your trystit wife intil your hame; the bairn she is cairrein is o the Halie Spírit. She will beir a son, an the name ye ar tae gíe him is Jesus, for he will sauf his fowk frae their sins."

Aa this happent at the wurd spokken bi the Lord throu the Prophet micht be fulfilled: Behaud, the virgin wil bouk an beir a son, an they will caa his name Immanuel – that is, "God wi us".

Whan he hed waukit frae his sleep, Joseph did as the angel hed bidden him, an tuik his trystit wife hame wi him. But he bedditna wi her or she buir a son; an he caa'd the bairn Jesus.

— Matthew 1:18–21

- Bungi Creole of the Canadian Metis people of Scottish/British descent

- Doric dialect (Scotland)

- Glasgow patter

- Billy Kay

- Languages of the United Kingdom

- Phonological history of Scots

- Scotticism

- Scottish Corpus of Texts and Speech

- Scottish literature

- The endonym for Scots is Scots [skɔts] and in Scottish Gaelic: Beurla Ghallda or Albais.

- "Scotland's Census 2011" (PDF). 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2014. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- "Fact: Scotland's official languages are English, Scots, Gaelic & British Sign Language". Scotland.org. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- "List of declarations made with respect to treaty No. 148". Conventions.coe.int. Archived from the original on 9 July 2011. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- "Gaelic Language". cranntara.scot.

- Horobin, Simon; Smith, Jeremy (2002). An Introduction to Middle English. Oup USA. ISBN 978-0-19-521950-0. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- Alexander Bergs, Modern Scots, Languages of the World series, № 242 (Bow Historical Books, 2001), ISBN 978-3-89586-513-8, pp. 4, 50. "Scots developed out of a mixture of Scandinavianised Northern English during the early Middle English period.... Scots originated as one form of Northern Old English and quickly developed into a language in its own right up to the seventeenth century."

- Sandred, Karl Inge (1983). "Good or Bad Scots?: Attitudes to Optional Lexical and Grammatical Usages in Edinburgh". Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. 48. Ubsaliensis S. Academiae: 13. ISBN 978-91-554-1442-9.

Whereas Modern Standard English is traced back to an East Midland dialect of Middle English, Modern Scots developed from a northern variety which goes back to Old Northumbrian

- "Scots language policy: English version - gov.scot". www.gov.scot.

- "UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in danger". www.unesco.org. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- Evans, Lisa (15 April 2011). "Endangered languages: the full list". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- "Ethnicity, Identity, Language and Religion | Scotland's Census". Scotland's Census.

- Aitken, A. J. (1992). The Oxford Companion to the English Language. Oxford University Press. p. 894.

- "Scottish National Dictionary (1700–): Scots, adj". Dsl.ac.uk. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- "Scottish National Dictionary (1700–): Doric". Dsl.ac.uk. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- Buchan, Peter; Toulmin, David (1998). Buchan Claik: The Saut and the Glaur O't: a Compendium of Words and Phrases from the North-east of Scotland. Gordon Wright. ISBN 978-0-903065-94-8.

- Traynor, Michael (1953). The English dialect of Donegal. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy. p. 244.

- Nic Craith, M. (2002). Plural Identities—singular Narratives. Berghahn Books. p. 107.

- "Scottish National Dictionary (1700–): Lawland, adj". Dsl.ac.uk. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- "Ethnologue – Scots". Ethnologue. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- Tymoczko, M.; Ireland, C.A. (2003). Language and Tradition in Ireland: Continuities and Displacements. University of Massachusetts Press. p. 159. ISBN 1-55849-427-8.

- "Scots, a. (n.)". OED online. Archived from the original on 26 December 2019. Retrieved 28 July 2020.

- "A Brief History of Scots". Scotslanguage.

- Bingham, Caroline (1974). The Stewart Kingdom of Scotland, 1371–1603. Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

- McArthur, Tom (1994). Companion to the Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press.

- The British Isles about 802 (Map). 1:7 500 000.

- "cairt n. v.". The Online Scots Dictionary.

- Macafee, Caroline; Aitken, A.J. (2002). "A History of Scots to 1700". A Dictionary of the Older Scottish Tongue. Vol. 12. Dictionary of the Scots Language. p. xxxvi. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- "Dictionaries of the Scots Language – vocabulary". Retrieved 30 April 2021.

- Corbett, John; McClure, Derrick; Stuart-Smith, Jane, eds. (2003). "A Brief History of Scots". The Edinburgh Companion to Scots. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 9. ISBN 0-7486-1596-2.

- Montgomery & Gregg 1997: 572

- Adams 1977: 57

- Murray, James Augustus Henry (1873). The dialect of the southern counties of Scotland : its pronunciation, grammar, and historical relations; with an appendix on the present limits of the Gaelic and lowland Scotch, and the dialectical divisions of the lowland tongue; and a linguistical map of Scotland. Asher & Co.

- Petyt, Keith Malcolm (1980). The Study of Dialect: An introduction to dialectology. Andre Deutsch. pp. 94–98. ISBN 0-233-97212-9.

- Eder, Birgit (2004). Ausgewählte Verwandtschaftsbezeichnungen in den Sprachen Europas: untersucht anhand der Datensammlungen des Atlas Linguarum Europae. Peter Lang. p. 301. ISBN 978-3-631-52873-0.

- "A Speach in Parliament. Anno 1603" in "The Workes of the Most High and Mightie Prince Iames, by the Grace of God" (1616), pg. 485

- Jones, Charles (1995). A Language Suppressed: The Pronunciation of the Scots Language in the 18th Century. Edinburgh: J. Donald Publishers. p. vii. ISBN 0-85976-427-3.

- "Scuilwab, p.3" (PDF).

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- "The Dialect Dictionary: meeting in Bradford". Bradford Observer. 7 October 1895.

- Eagle, Andy (2006). "Aw Ae Wey – Written Scots in Scotland and Ulster" (PDF). Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- Primary education: a report of the Advisory Council on Education in Scotland, Scottish Education Department 1946, p. 75

- Macafee, C. (2003). "Studying Scots Vocabulary". In Corbett, John; McClure, Derrick; Stuart-Smith, Jane (eds.). The Edinburgh Companion to Scots. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 51. ISBN 0-7486-1596-2.

- Jones, Charles (1997). The Edinburgh History of the Scots Language. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 518. ISBN 978-0-7486-0754-9. Retrieved 9 August 2010.

Menzies (1991:42) also found that in her sample of forty secondary-school children from Easterhouse in Glasgow, there was a tendency to describe Scots words as 'slang' alongside the use of the term 'Scots'

- The Scottish Government. "Public Attitudes Towards the Scots Language". Archived from the original on 1 April 2017. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- Horsbroch, Dauvit. "Nostra Vulgari Lingua: Scots as a European Language 1500–1700". www.scots-online.org. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- Kloss, Heinz, ²1968, Die Entwicklung neuer germanischer Kultursprachen seit 1800, Düsseldorf: Bagel. pp.70, 79

- Jane Stuart-Smith (2004). "Scottish English: phonology". In Bernd Kortmann and Edgar W. Schneider (ed.). A Handbook of Varieties of English. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 48–49. ISBN 978-3-11-017532-5.

- Scott, Maggie (November 2007). "The Scots Continuum and Descriptive Linguistics". The Bottle Imp. Association for Scottish Literary Studies. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- See for example "Confession of Faith Ratification Act 1560". Archived from the original on 26 August 2020., written in Scots and still part of British Law

- "Scots language being revived in schools". BBC News. 13 February 2015.

- "Knowledge of Language: Scots: Scots and Curriculum for Excellence". Education Scotland. Archived from the original on 14 October 2016. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- "Exposed to ridicule". The Scotsman. 7 February 2004. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- "Scots – Teaching approaches – Learning and Teaching Scotland Online Service". Ltscotland.org.uk. 3 November 2005. Archived from the original on 30 October 2004. Retrieved 21 May 2009.

- "National Guidelines 5–14: ENGLISH LANGUAGE Learning and Teaching Scotland Online Service". Ltscotland.org.uk. Archived from the original on 6 October 2008. Retrieved 21 May 2009.

- "OLCreate: Scots language and culture". Archived from the original on 26 August 2020. Retrieved 22 December 2019.

- "Scottish government website" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 July 2023.

- "Planning the 2022 census | Scotland's Census". Scotland's Census. Archived from the original on 26 August 2020. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- "The Scottish Parliament: – Languages – Scots". Scottish Parliament. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- "The National at the fore of dictionary updates of Scots language". The National. 22 March 2019.

- "Scotslanguage.com – Children's books in Scots". www.scotslanguage.com.

- "Book List: Scots books for 9–14 year olds". Scottish Book Trust. Retrieved 21 October 2021.

- "Singer wins campaign to persuade Spotify to recognise Scots language for first time". The Scotsman. 4 March 2021.

- Caroline I. Macafee (ed.), A Concise Ulster Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996; pp. xi–xii.

- Maguire, Warren (2020). Language and Dialect Contact in Ireland: The Phonological Origins of Mid-Ulster English. Edinburgh University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-4744-5290-8.

- [Iain Máté] (1996) Scots Language. A Report on the Scots Language Research carried out by the General Register Office for Scotland in 1996, Edinburgh: General Register Office (Scotland).

- Steve Murdoch, Language Politics in Scotland (AUSLQ, 1995), p. 18

- "The Scots Language in education in Scotland" (PDF). Regional Dossiers Series. Mercator-Education. 2002. ISSN 1570-1239.

- T.G.K. Bryce and Walter M. Humes (2003). Scottish Education. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 263–264. ISBN 978-0-7486-1625-1.

- "Pupils in Scotland, 2008". Scotland.gov.uk. 1 April 2009. Archived from the original on 26 August 2020. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- "Scottish Census Day 2011 survey begins". BBC News. 26 March 2011. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- "Scots language – Scottish Census 2011". Aye Can. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- "How to fill in your questionnaire: Individual question 16". Scotland's Census. General Register Office for Scotland. Archived from the original on 1 March 2011. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- "Scotland's Census 2011: Standard Outputs". National Records of Scotland. Archived from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- William Donaldson, The Language of the People: Scots Prose from the Victorian Revival, Aberdeen University Press 1989.

- Bairnsangs ISBN 978-0-907526-11-7

- Andy Eagle (26 July 2005). "Wir Ain Leed – An introduction to Modern Scots". Scots-online.org. Retrieved 15 September 2012.

- Aitken A. J. "How to Pronounce Older Scots" in Bards and Makars. Glasgow University Press 1977

- "SND INTRODUCTION". 22 September 2012. Archived from the original on 22 September 2012.

- Johnston, Paul (1997). "Regional Variation". In Jones, Charles (ed.). The Edinburgh History of the Scots Language. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 510.

- Agutter, Alex (1987) "A taxonomy of Older Scots orthography" in Caroline Macafee and Iseabail Macleod eds. The Nuttis Schell: Essays on the Scots Language Presented to A. J. Aitken, Aberdeen University Press, p. 75.

- Millar, Robert McColl (2005) Language, Nation and Power An Introduction, Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke. pp. 90–91

- Wilson, James (1926) The Dialects of Central Scotland, Oxford University Press. p.194

- Tulloch, Graham (1980) The Language of Walter Scott. A Study of his Scottish and Period Language, London: Deutsch. p. 249

- Grant, William; Murison, David D. (eds.). The Scottish National Dictionary (SND) (1929–1976). Vol. I. Edinburgh: The Scottish National Dictionary Association. p. xv.

- McClure, J. Derrick (1985) "The debate on Scots orthography" in Manfred Görlach (ed.), Focus on: Scotland, Amsterdam: Benjamins, p. 204

- Mackie, Albert D. (1952) "Fergusson's Language: Braid Scots Then and Now" in Smith, Sydney Goodsir ed. Robert Fergusson 1750–1774, Edinburgh: Nelson, p. 123–124, 129

- Mairi Robinson (editor-in-chief), The Concise Scots Dictionary, Aberdeen University Press, 1985 p. xiii

- Stevenson, R.L. (1905). The Works of R. L. Stevenson Vol. 8, "Underwoods", London: Heinemann, p. 152

- Todd, Loreto (1989). The Language of Irish Literature, London: Macmillan, p. 134

- Grant, William; Dixon, James Main (1921). Manual of Modern Scots. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- McClure, J. Derrick (2002). Doric: The Dialect of North–East Scotland. Amsterdam: Benjamins, p. 79

- Eagle, Andy (2014). "Aw Ae Wey—Written Scots in Scotland and Ulster" (PDF). v1.5.

- Rennie, S. (2001) "The Electronic Scottish National Dictionary (eSND): Work in Progress", Literary and Linguistic Computing, 2001 16(2), Oxford University Press, pp. 159

- Beal, J. "Syntax and Morphology". In Jones, C. (ed.). The Edinburgh History of the Scots Language. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh Press. p. 356.

- "SND Introduction - Dialect Districts. p.xxxi". Dsl.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 21 January 2012. Retrieved 21 May 2009.

This section's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (July 2015) |

- Scots-online

- The Scots Language Society

- Scots Language Centre

- Scots at Omniglot

- a phonetic description of Scottish Language and Dialects at Dictionary of the Scots Language

- Words Without Borders Peter Constantine: Scots: The Auld an Nobill Tung

- Scots in Schools

Dictionaries and linguistic information

Collections of texts

- ScotsteXt – books, poems and texts in Scots

- Scots Threap

- Scottish Corpus of Texts & Speech – Multimedia corpus of Scots and Scottish English

- BBC Voices, Scots section – The BBC Voices Project is a major, though informal, look at UK language and speech

- Scots Syntax Atlas