Sixth_Avenue_Elevated

IRT Sixth Avenue Line

Former New York City rapid transit line

The IRT Sixth Avenue Line, often called the Sixth Avenue Elevated or Sixth Avenue El, was the second elevated railway in Manhattan in New York City, following the Ninth Avenue Elevated.

| IRT Sixth Avenue Line | |

|---|---|

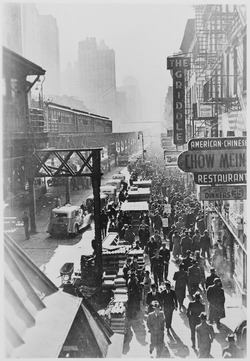

New York City's Sixth Avenue elevated railway and the crowded street below | |

| Overview | |

| Owner | City of New York |

| Termini | |

| Service | |

| Type | Rapid transit |

| System | Interborough Rapid Transit Company |

| Operator(s) | Interborough Rapid Transit Company |

| History | |

| Opened | 1878 |

| Closed | 1938 |

| Technical | |

| Number of tracks | 2-3 |

| Character | Elevated |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) |

The line ran south of Central Park, mainly along Sixth Avenue. Beyond the park, trains continued north on the Ninth Avenue Line.

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2017) |

The elevated line was constructed during the 1870s by the Gilbert Elevated Railway, subsequently reorganized as the Metropolitan Elevated Railway. The line opened on June 5, 1878 between Rector Street and 58th Street.[1] Its route ran north from the corner of Rector Street and Trinity Place up Trinity Place / Church Street, then west for a block at Murray Street, then north again on West Broadway, west again across West 3rd Street to the foot of Sixth Avenue, and then north to 59th Street. The following year, ownership passed to the Manhattan Railway Company, which also controlled the other elevated railways in Manhattan. In 1881, the line was connected to the largely rebuilt Ninth Avenue Elevated; it was joined in the south at Morris Street, and in the north by a connecting link running across 53rd Street. And it ran 24/7.[2]

Due to its central location in Manhattan and the inversion of the usual relationship between street noise and height,[clarification needed] the Sixth Avenue El attracted artists; in addition to being the subject of several paintings by John French Sloan, it was also painted by Francis Criss and others.[3]

As of 1934, the following services were being operated:

- 6th Avenue Local - South Ferry to 155th Street all hours, extended to Burnside Avenue via Jerome Avenue Line weekday and Saturday evenings.

- 6th Avenue Express - Rector Street to Burnside Avenue via Jerome Avenue Line - weekday and Saturday peak hours. Trains ran express on Ninth Avenue southbound in the morning and northbound in the evening, and made all stops in the reverse direction.

As with many elevated railways in the city, the Sixth Avenue El made life difficult for those nearby. It was noisy, it made buildings shake, and in the line's early years, it dropped ash, oil, and cinders on pedestrians below.[4] Eventually, a coalition[who?] of commercial establishments and building owners along Sixth Avenue campaigned to have the El removed, on the grounds that it was depressing business and property values.

In 1936, work started on the underground Sixth Avenue Line, operated by the city as part of the Independent Subway System (IND).[5] As part of the plan, three of New York City's private subway companies (the IND; the IRT; and the Brooklyn–Manhattan Transit Corporation, or BMT) would be combined into one system, and the IRT Sixth Avenue elevated would be demolished.[6] The city of New York acquired the line from the bondholders of the Manhattan Railway Company for $12,500,000, of which the city recovered $9,010,656 in back taxes and interest, in 1938.[7] Subsequently, the El was closed on December 4, 1938.[8] It was razed during 1939 to make way for the IND line. The section of the IND line that was located under Sixth Avenue opened in December 1940.[5]

The footings for the elevated were rediscovered in the early 1990s during a Sixth Avenue renovation project.[9]

Allegations demolition scrap was sold to Japan

In order to alleviate any concern that the scrap metal might be exported to the Japanese, demolition contractor Tom Harris, who had received $40,000 to demolish the structure provided affidavits to the New York City Council that none of the iron would leave the United States.[10] The inaccurate rumors were later included within the lines of E. E. Cummings's 1944 poem "plato told."[11]

Twenty thousand tons of scrap metal from the El was sold to a dealer on the west coast[who?] who was in the export business. The New York Times pointed out in December 1938 that even if the scrap did not go directly to Japan, for possible use against China, such a large amount of scrap metal arriving on the market would free up metal to be sent to Japan.[12]

At a meeting of the New York City Board of Estimate in 1942, Stanley M. Isaacs, the Manhattan Borough President, denied that steel from the El was sold to Japan. Isaacs said that when the demolition contract was drafted in 1938, "at my insistence the contract provided that not one ounce of that steel could be exported to Japan or to any one else."[13] Isaacs said that the contractor was prohibited from exporting the steel from the El, and carried out his obligation to the letter.[14]

Reports[which?] of the supposed sale of the scrap to Japan persisted. In 1961, an attorney for the Harris Structural Steel Company, which was involved in the demolition, told syndicated columnist George Sokolsky that continued reports of the sale of steel from the El to Japan were not accurate. The attorney said that none of the steel from the El reached Japan directly or indirectly.[15]

All trains ran local, express trains utilized the Ninth Avenue express stations north of 53rd Street.

| Station | Opening date | Closing date | Transfers and notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 59th Street | June 9, 1879[16] | June 11, 1940 | Ninth Avenue Line |

| Eighth Avenue | 1881 | December 4, 1938[8] | |

| 58th Street Terminal | June 5, 1878 | June 16, 1924 | Former northern terminal |

| 50th Street | June 5, 1878 | December 4, 1938[8] | |

| 42nd Street | June 5, 1878 | December 4, 1938[8] | |

| 38th Street | January 31, 1914[17][18] | December 4, 1938[8] | |

| 33rd Street | June 5, 1878 | December 4, 1938[8] | |

| 28th Street | 1892 | December 4, 1938[8] | |

| 23rd Street | June 5, 1878 | December 4, 1938[8] | |

| 18th Street | 1892 | December 4, 1938[8] | |

| 14th Street | June 5, 1878 | December 4, 1938[8] | |

| Eighth Street | June 5, 1878 | December 4, 1938[8] | |

| Bleecker Street | June 5, 1878 | December 4, 1938[8] | |

| Grand Street | June 5, 1878 | December 4, 1938[8] | |

| Franklin Street | June 5, 1878 | December 4, 1938[8] | |

| Chambers Street | June 5, 1878 | December 4, 1938[8] | |

| Park Place | June 5, 1878 | December 4, 1938[8] | |

| Cortlandt Street | June 5, 1878 | December 4, 1938[8] | |

| Rector Street | June 5, 1878 | December 4, 1938[8] | |

| Battery Place | June 5, 1883[19] | June 11, 1940 | Ninth Avenue Line |

| South Ferry | April 5, 1877 | Second, Third, and Ninth Avenue Lines; various ferries |

- Superior Court of the City of New York, General Term. 1888. p. 195.

- Arnaudin, Edwin. "Arts | Mountain Xpress". Mountainx.com. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- Fischler, Stan (1976). Uptown, Downtown: A Trip Through Time on New York's Subways. New York: Hawthorn Books. p. 33. ISBN 0801531187.

- "New Subway Line on 6th Ave. Opens at Midnight Fete". The New York Times. December 15, 1940. pp. 1, 56. Retrieved October 7, 2011.

- "ELEVATED RAZING IN 6TH AV. UPHELD; Counsel to Civic Group Says Demolition Would Not Violate City's Contract With I.R.T." The New York Times. 1936. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 26, 2018.

- "Elevated to seek 7-cent fare soon" (PDF). The New York Times. January 10, 1939.

- "GAY CROWDS ON LAST RIDE AS SIXTH AVE. ELEVATED ENDS 60-YEAR EXISTENCE; 350 POLICE ON DUTY But the Noisy Revelers Strip Cars in Hunt for Souvenirs SUIT MAY DELAY RAZING Little Threat Seen to Plan, However-Jobless Workers to Press Their Protest Makes Only One Stop Entrances Are Boarded Up FINAL TRAINS RUN ON ELEVATED LINE Police Guard Structure". The New York Times. December 5, 1938. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 26, 2018.

- NYC rehabilitates Sixth Avenue American Cit and County, February 1, 1996 Archived November 26, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- The Minneapolis Star Tribune, Feb. 18, 1938, p.18

- "Topics of the Times: Whither Sixth Avenue". Lapham's Quarterly. March 6, 2012. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- "Topics of the Times: Whither Sixth Avenue" (PDF). The New York Times. December 7, 1938. Retrieved August 12, 2011.

- "Estimate Board Dooms 2nd Ave. 'El'" (PDF). The New York Times. May 29, 1942. Retrieved August 12, 2011.

- "Transit Body Gets El Demolition Job" (PDF). The New York Times. June 7, 1940. Retrieved August 12, 2011.

- Sokolsky, George (September 19, 1961). "Congressional Probe of Dealings with Reds Urged". The Florence Times. Florence, Alabama. Retrieved August 12, 2011.

- "The Manhattan Company — Opening of the West Side to Eighty-first Street — The Sunday Trains" (PDF). New York Times. June 10, 1879. p. 8. Retrieved February 11, 2009.

- "38th Street Elevated Station Open", The New York Times, February 1, 1914, accessed January 7, 2016.

- "Transit Benefits for 38th Street", The New York Times, February 9, 1913, accessed March 29, 2011.

- "A Station at Battery Place". New York Times. June 5, 1883. p. 5. Retrieved September 22, 2020.

- Jackson, Kenneth T. (ed.), The Encyclopedia of New York City, "Elevated Railways", Yale University Press, 1995. ISBN 978-0-300-05536-8.