Sultanate_of_Makassar

Sultanate of Gowa

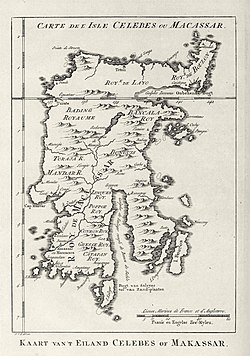

Former sultanate in Southern Sulawesi

The Sultanate of Gowa (sometimes written as Goa; not to be confused with Goa in India) was one of the great kingdoms in the history of Indonesia and the most successful kingdom in the South Sulawesi region. People of this kingdom come from the Makassar tribe who lived in the south end and the west coast of southern Sulawesi.

Sultanate of Gowa | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14th century–1957 | |||||||||||

|

Flag | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Capital | Tamalate (1320–1548) Somba Opu (1548–1670) Jongaya (1895–1906) Sungguminasa (1936–present) | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Makassarese | ||||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| Sultan, Karaeng Sombayya ri Gowa | |||||||||||

• 1300 | Tumanurung | ||||||||||

• 1653-1669 | Sultan Hasanuddin | ||||||||||

• 1946-1957 | Sultan Aiduddin | ||||||||||

• 2021-present | Sultan Malikussaid II, Andi Kumala Idjo | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

• Established | 14th century | ||||||||||

• Dissolution of Sultanate | 1957 | ||||||||||

| Currency | Jingaraʼ, Gold and copper coins was used in circulation, the Barter system was used | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | Indonesia (as Gowa Regency) | ||||||||||

Before the establishment of the kingdom, the region had been known as Makassar and its people as Makassarese.[1] The history of the kingdom can be divided into two eras: pre-Islamic kingdom and post-Islamic sultanate.

Pre-Islamic Kingdom

According to the epic poem the Nagarakretagama, in praise of King Rajasanagara of Majapahit, it lists Makassar as one of the kingdom's tributaries in 1365.[2]

The first queen of Gowa was Tomanurung Baine.[1] There is not much known about the exact time when the kingdom was established nor about the first queen, and only during the ruling of the 6th king, Tonatangka Kopi, local sources have noted about the division of the kingdom into two new kingdoms led by two Kopi's sons: Kingdom of Gowa led by Batara Gowa as its 7th king covering areas of Paccelekang, Pattalasang, Bontomanai Ilau, Bontomanai 'Iraya, Tombolo and Mangasa while the other son, Karaeng Loe ri Sero, led a new kingdom called Tallo which includes areas of Saumata, Pannampu, Moncong Loe, and Parang Loe.[1]

For years both kingdoms were involved in wars until the kingdom of Tallo was defeated. During the reign of King of Gowa X, I Manriwagau Daeng Bonto Karaeng Lakiung Tunipalangga (1512-1546), the two kingdoms were reunified to become twin kingdoms under a deal called Rua Kareng se're ata (dual kings, single people in Makassarese) and enforced with a binding treaty.[1] Since then, when someone becomes a king of Tallo, he also becomes the king of Gowa. Many historians then simply call these Gowa-Tallo twin kingdoms as Makassar or just Gowa.[1]

Islamic Sultanate

The traces of Islam in South Sulawesi existed since the 1320s with the arrival of the first Sayyid in South Sulawesi, namely Sayyid Jamaluddin al-Akbar Al-Husaini, who is the grandfather of Wali Songo.[3]

The conversion of the kingdom to Islam is dated as September 22, 1605 when the 14th king of Tallo-Gowa kingdom, Karaeng Matowaya Tumamenaga Ri Agamanna, converted to Islam,[4] where later changed his name to Sultan Alauddin. He ruled the kingdom from 1591 to 1629. His conversion to Islam is associated with the arrival of three ulama from Minangkabau: Datuk Ri Bandang, Datuk Ri Tiro and Datuk Ri Pattimang.[5]

From 1630 until the early twentieth century, Gowa's political leaders and Islamic functionaries were both recruited from the ranks of the nobility.[4] Since 1607, sultans of Makassar established a policy of welcoming all foreign traders.[2] In 1613, an English factory built in Makassar. This began the hostilities of English-Dutch against Makassar.[2]

The most famous Sultan of the kingdom was Sultan Hasanuddin, who from 1666 to 1669 started a war known as Makassar War against the Dutch East India Company (VOC) which was assisted by the prince of Bone kingdom of Bugis dynasty, Arung Palakka.[6]

Islamic wars

The Sultanate of Gowa's patronage of Islam caused it to try and encourage neighboring kingdoms to accept Islam, an offer which they refused. In response in 1611, the sultanate launched a series of campaigns, called locally the "Islamic wars", which resulted in all of southwest Sulawesi, including their rival Bone, being subjugated and subsequently Islamized. The war later extended to Sumbawa, which was invaded in 1618 and the rulers were forced to convert to Islam.[7] Religious zeal from the rulers were an important factor behind the campaigns, as they saw the conquests as a justified religious act.[8][9] However, Gowa also desired to expand the political and economic influence of Gowa as it experienced rapid political growth during the 17th century.[10][11][9] It was a subsequent stage in a historical rivalry between the states of the region for political control.[11]

According to Indonesian historian Daeng Patunru, in the case of the Bugis kingdoms, the ruler of Gowa initially conquered them due to their growing political power which would undermine Gowa's authority and sphere of influence.[12] Other scholars contend that the conflict with the Bugis was originally started due to the upholding of an old treaty that stated that Gowa and the Bugis kingdoms were to share and convince the others if they were to discover "a spark of goodness" which in this case Gowa contended was the religion of Islam.[13]

Varying levels of resistance against Gowa from nearby states to consider Islam and its military forces determined the relationship the defeated state would have with Gowa, which were based on socially hierarchical kinship positions.[8][11] This included strict vassalage and defeated rulers and populations having subordinate or enslaved positions within the empire.[8][14] This scheme of hierarchical relations and subordinate positions in relation to a more powerful state has ancient roots in the region which predate Islam.[8] The one difference added to this ancient tradition was that the defeated ruler had to profess the shahadah which also served as an acceptance of submission to Gowa.[11] The defeated populations of the states were not commonly forced to convert.[14]

After the conquests, Gowa pursued a policy of religious proselytization within the defeated kingdoms, which included sending Javanese preachers to teach the religion among the masses and establish Islamic institutions.[14]

Makassar War

In 1644, Bone rose up against Gowa. The Battle of Passempe saw Bone defeated and a regent heading an Islamic religious council installed. In 1660 Arung Palakka, the long haired prince of the Sultanate of Bonu,[15] led a Bugis revolt against Gowa, but failed.[2]

In 1666, under the command of Admiral Cornelis Speelman, The Dutch East India Company (VOC) attempted to bring the small kingdoms in the North under their control, but did not manage to subdue the Sultanate of Gowa. After Sultan Hasanuddin ascended to the throne as the 16th sultan of Gowa, he tried to combine the power of the small kingdoms in eastern Indonesia to fight the VOC.

On the morning of 24 November 1666, the VOC expedition and the Eastern Quarters set sail under the command of Speelman. The fleet consisted of the admiralship Tertholen, and twenty other vessels carrying some 1860 people, among them 818 Dutch sailors, 578 Dutch soldiers, and 395 native troops from Ambon under Captain Joncker and from Bugis under Arung Palakka and Arung Belo Tosa'deng.[16] Speelman also accepted Sultan Ternate's offer to contribute a number of his war canoes for the war against Gowa. A week after June 19, 1667, Speelman's armada set sail toward Sulawesi and Makassar from Butung.[16] When the fleet reached the Sulawesi coast, Speelman received news of the abortive Bugis uprising in Bone in May and of the disappearance of Arung Palakka during the crossing from the island of Kambaena.

The war later broke in 1666 between the VOC and the sultanate of Gowa.[17] The war continued until 1669, after the VOC had landed its strengthened troops in a desperate and ultimately weakening Gowa. On 18 November 1667 the Treaty of Bungaya was signed by the major belligerents in a premature attempt to end the war.[16]

Feeling aggrieved, Hasanuddin started the war again. Finally, the VOC requested assistance for additional troops from Batavia. Battles broke out again in various places with Sultan Hasanuddin giving fierce resistance. Military reinforcements sent from Batavia strengthened the VOC's military capability, allowing it to break the Sultanate of Gowa's strongest fortress in Somba Opu on June 12, 1669, which finally marked the end of the war. Sultan Hasanuddin resigned from the royal throne, dying on June 12, 1670.

After the Makassar war, Admiral Cornelis Speelman destroyed the large fortress in Somba Opu, and built up Fort Rotterdam (Speelman named this fortress after his birthplace in Netherlands) in its place as the headquarters of VOC activities in Sulawesi. In 1672 Arung Palakka was raised to the throne to become the sultan of Bone.

Dissolution of Sultanate

Since 1673 the area around Fort Rotterdam grew into a city currently known as Makassar.[18] Since 1904 the Dutch colonial government had engaged in the South Sulawesi expedition and started war against small kingdoms in South Sulawesi, including Gowa. In 1911 the Sultanate lost its independence after losing the war and became one of the Dutch Indies' regencies.[19] Following the Indonesian Independence from Netherlands in 1945, the sultanate dissolved and has since become part of the Republic of Indonesia and the former region becomes part of Gowa Regency.

Political administration

The variety of titles used by leaders of small polities is bewildering: anrongguru, dampang, gallarrang, jannang, kare, kasuiang, lao, loqmoq, todo, and more besides. All were local titles Makassarese used before the rise of Gowa. Gowa's expansion brought some systematic order to this variety.[20]: 113

Granting titles was an important method of establishing and recognizing a given person/s and a given community's place within society. Ideally, but not always in fact, this hierarchy of titles corresponded to the natural hierarchy of the white blood that the nobles possessed. Distinguishing nobles from commoners, for example, was the right to have a royal or daeng name as well as a personal name. Distinguishing lower ranking nobles such as anaq ceraq from higher-ranking nobles like anaq tiqno was the latter's right to a karaeng title. Granted by the ruler of Gowa, karaeng titles not only signified the bearer's accepted high status, but were often toponyms that gace the bearer the right to demand tribute and labor from the community of that name.[20]: 113

Offices did become the domain of the nobles with karaeng titles. The most important of these was Tumabicarabutta, whose task it was to assist the ruler of Gowa as regent and chief advisor. This pattern of the ruler of Talloq advising the ruler of Gowa became the norm in the first part of the 17th century.[20]: 112

Another important office was Tumailalang (literally, "the person on the inside"), the trio of ministers. From the title it appears that the Tumailalang were inchange of managing everyday affairs within Gowa, there was a join tumailalang-sabannaraq office during the reign of Tumapaqsiriq Kallonna. During the subsequent reign, Tunipalannga separated these offices and by the reign of Tunijalloq, there were 2 Tumailalang, later known as the elder tumailalang toa and the younger tumailalang lolo. All holders of the Tumailalang posts were high-ranking karaengs.[20]: 112

Rulers of Gowa used the title Karaeng Sombayya ri Gowa meaning "the king who is worshipped in Gowa", shortened to Karaenga Gowa, Sombayya ri Gowa. Islamic period of Gowa started during the reign of I Mangarangi Daeng Manrabbiya Sultan Alauddin in 1605.[21]: 839

| No | Monarch | Lifetime | Reign | Additional info |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tumanurung | Mid-14th century | ||

| 2 | Tumassalangga Baraya | |||

| 3 | I Puang Loe Lembang | |||

| 4 | Tuniatabanri | |||

| 5 | Karampang ri Gowa | |||

| 6 | Tunatangkalopi | |||

| 7 | Batara Gowa, titled Tumenanga ri Parallakkenna | |||

| 8 | Tunijalloʼ ri Passukkiʼ | 1510 | ||

| 9 | Tumapaʼrisiʼ Kallonna | 1511 - 1546 | ||

| 10 | I Manriwagauʼ Daeng Bonto Karaeng Lakiung Tunipallangga | 1546 - 1565 | ||

| 11 | I Tajibarani Daeng Marompa Karaeng Dataʼ Tunibatte | 1565 (only 40 days) | ||

| 12 | I Manggorai Daeng Mammeta Tunijalloʼ | 1545 - 1590 | ||

| 13 | I Tepukaraeng Daeng Paraʼbung Tunipasuluʼ (deposed) | 1590 - 1593 | ||

| 14 | I Manngarangi Daeng Manrabbia Sultan Alauddin, titled Tumenanga ri Gaukanna | 1586 - 15 June 1639 | 1593 - 15 June 1639 | |

| 15 | I Mannuntungi Daeng Mattola Karaeng Lakiung Sultan Malikussaid, titled Tumenanga ri Papambatuna | 11 Dec 1607 - 5 Nov 1653 | 1639 - 5 Nov 1653 | |

| 16 | I Mallombassi Daeng Mattawang Karaeng Bontomangape Sultan Hasanuddin, titled Tumenanga ri Ballaʼ Pangkana | 12 Jan 1631 - 12 June 1670 | 1653 - 17 June 1669 | |

| 17 | I Mappasomba Daeng Nguraga Sultan Amir Hamzah, titled Tumenanga ri Alluʼ | 31 Mar 1657 - 7 May 1674 | 1669 - 1674 | |

| 18 | I Mappaossong Daeng Mangewai Karaeng Bisei Sultan Muhammad Ali, titled Tumenanga ri Jakattaraʼ | 29 Nov 1654 - 15 Aug 1681 | 1674 - 1677 | |

| 19 | I Mappadulung Daeng Mattimung Karaeng Sanrobone Sultan Abdul Jalil, titled Tumenanga ri Lakiung | 1677 - 1709 | ||

| 20 | La Pareppa Tusappewali Sultan Ismail, titled Tumenanga ri Somba Opu | 1709 - 1712 | ||

| 21 | I Mappauʼrangi Karaeng Kanjilo Sultan Sirajuddin, titled Tumenanga ri Pasi | 1712 - 1735 | ||

| 22 | I Mallawanggauʼ Sultan Abdul Khair | 1735 - 1739 | 1739 - 1742 | |

| 23 | I Mappasempe Daeng Mamaro Karaeng Bontolangkasaʼ | 1739 | ||

| 24 | I Mappababasa Sultan Abdul Kudus | 1742 - 1753 | ||

| 25 | Batara Gowa Sultan Fakhruddin (exiled to Sri Lanka) | 1753 - 1767 | ||

| 26 | I Mallisujawa Daeng Riboko Arungmampu Sultan Imaduddin, titled Tumenanga ri Tompobalang | 1767 - 1769 | ||

| 27 | I Makkaraeng Karaeng Tamasongoʼ Sultan Zainuddin, titled Tumenanga ri Mattowanging | 1769 - 1777 | ||

| 28 | I Mannawarri Karaeng Bontolangkasaʼ Sultan Abdul Hadi | 1779 - 1810 | ||

| 29 | I Mappatunru Karaeng Lembangparang, titled Tumenanga ri Katangka | 1816 - 1825 | ||

| 30 | Karaeng Katangka Sultan Abdul Rahman, titled Tumenanga ri Suangga | 1825 | ||

| 31 | I Kumala Karaeng Lembangparang Sultan Abdul Kadir, titled Tumenaga ri Kakuasanna | d. on 30 January 1893 | 1825 - 30 Jan 1893 | |

| 32 | I Mallingkaang Daeng Manyonri Karaeng Katangka Sultan Idris, titled Tumenanga ri Kalabbiranna | d. 18 May 1895 | 1893 - 18 May 1895 | |

| 33 | I Makkulau Daeng Serang Karaeng Lembangparang Sultan Husain, titled Tumenang ri Bundu'na | 18 May 1895 - 13 April 1906 | ||

| 34 | I Mangimangi Daeng Matutu Karaeng Bontonompoʼ Sultan Muhibuddin, titled Tumenanga ri Sungguminasa | 1936 - 1946 | ||

| 35 | Andi Ijo Daeng Mattawang Karaeng Lalolang Sultan Aiduddin | d. 1978 | 1946 - 1957 | 1957 - 1960 as the first Regent of Gowa Regency |

- Burial place of the princes of Gowa (1)

- Burial place of the princes of Gowa (2)

- Burial place of the princes of Gowa (3)

- The arrival of Dutch authorities who would attend the signing of the Short Statement by Raja Gowa in Sungguminassa

- Raja (King) of Gowa signed the Brief Statement at his home

- Coronation of the Raja of Gowa

- On October 15, 1946, seven tribe rulers signed the Brief Declaration in front of the resident of South Sulawesi Lion Cachet

- Sewang, Ahmad M. (2005). Islamisasi Kerajaan Gowa: abad XVI sampai abad XVII (in Indonesian). Yayasan Obor Indonesia. ISBN 978-9-794615300.

- "MAKASSAR". Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- Hannapia, Muhammad Ali (2012). "Masuknya Islam di Gowa". muhalihannapia.blogspot.com (in Indonesian).

- Hefner, Robert W.; Horvatich, Patricia (1997). Robert W. Hefner; Patricia Horvatich (eds.). Islam in an Era of Nation-States: Politics and Religious Renewal in Muslim Southeast Asia. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-824819576.

- Sila, Muhammad Adlin (2015). "The Lontara': The Bugis-Makassar Manuscripts and their Histories". Maudu': A Way of Union with God. ANU Press. pp. 27–40. ISBN 978-1-925022-70-4. JSTOR j.ctt19893ms.10.

- Ricklefs, M.C. (2008). A History of Modern Indonesia Since C.1200 (revised ed.). Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137052018.

- Tarling, Nicholas. The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia, Volume 1.

By 1611 all southwest Sulawesi, including Makassar's Bugis rival Bone, had become Muslim. Only the mountainous area of Toraja did not succumb, primarily because the people here saw Islam as the faith of their traditional enemies. In 1618 Makassar undertook the first of several attacks on the island of Sumbawa to force recalcitrant local rulers to accept Islam. By the 1640s most neighboring kingdoms had accepted Makassar's overlordship and with it the Muslim faith. p.520

- Noorduyn, J. (1 January 1987). "Makasar and the islamization of Bima". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde / Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia. 143 (2): 312–342. doi:10.1163/22134379-90003330. ISSN 0006-2294.

- Cummings, William (2011). The Makassar annals. BRILL Publishers. p. 8. ISBN 978-90-04-25362-9. OCLC 1162616236.

- Sewang, Ahmad M. (2005). Islamisasi Kerajaan Gowa: abad XVI sampai abad XVII [The Islamization of the Kingdom of Gowa: From the 16th century until the 17th century] (in Indonesian). Yayasan Obor Indonesia. ISBN 978-979-461-530-0.

- Geoff, Wade (17 October 2014). Asian expansions: the historical experiences of polity expansion in Asia. Routledge. p. 225. ISBN 978-1-135-04353-7. OCLC 1100438409.

- Sila, Muhammad Adlin (2015). Maudu': A Way of Union with God. ANU Press. pp. 30–31. ISBN 978-1-925022-71-1.

- Federspiel, Howard M. (2007). Sultans, Shamans, and Saints: Islam and Muslims in Southeast Asia. University of Hawaii Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-8248-6452-1.

The rulers and populations of the defeated states were not forcibly converted to Islam, but the degree of resistance to the Makassarese forces and any refusal to consider Islam led to harsh terms of vassalage. Islamic propagators, mostly from Giri on Java, were sent to teach people the rudiments of religion and to establish Islamic institutions such as schools and retreats for mystics. Here is one of the clearest cases of proselytization being a primary policy of the state

- Esteban, Ivie Carbon (2010). "The Narrative of War in Makassar: Its Ambiguities and Contradictions". Sari - International Journal of the Malay World and Civilisation.

- Andaya, Leonard Y. (2013). The Heritage of Arung Palakka: A History of South Sulawesi (Celebes) in the Seventeenth Century. Vol. 91 of Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde (illustrated ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-9-401733472.

- Lach, Donald F.; Van Kley, Edwin J. (1998). Asia in the Making of Europe, Volume III: A Century of Advance. Book 3: Southeast Asia (illustrated, revised ed.). University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226467689.

- Backshall, Stephen (2003). Rough Guide Indonesia (illustrated ed.). Singapore: Rough Guides. ISBN 978-1-858289915.

- Elmer A. Ordoñez, ed. (1998). Toward the first Asian republic: papers from the Jakarta International Conference on the Centenary of the Philippine Revolution and the First Asian Republic. Philippine Centennial Commission. ISBN 978-971-92018-3-0.

- Cummings, William (2002). Making Blood White: Historical Transformations in Early Modern Makassar. University of Hawaiʻi Press. p. 257. ISBN 978-0-8248-2513-3.

- Watson, Noelle (2012). Asia and Oceania: International Dictionary of Historic Places. Routledge. p. 900. ISBN 978-1-136-63979-1.