United_States_presidential_election,_1972

1972 United States presidential election

47th quadrennial U.S. presidential election

The 1972 United States presidential election was the 47th quadrennial presidential election held on Tuesday, November 7, 1972. Incumbent Republican president Richard Nixon defeated Democratic U.S. senator George McGovern in a landslide victory. With 60.7% of the popular vote, Richard Nixon won the largest share of the popular vote for the Republican Party in any presidential elections.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

538 members of the Electoral College 270 electoral votes needed to win | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnout | 56.2%[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Presidential election results map. Red denotes states won by Nixon/Agnew and Blue denotes those won by McGovern/Shriver. Gold is the electoral vote for Hospers/Nathan by a Virginia faithless elector. Numbers indicate electoral votes cast by each state and the District of Columbia. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Nixon swept aside challenges from two Republican representatives in the Republican primaries to win renomination. McGovern, who had played a significant role in changing the Democratic nomination system after the 1968 presidential election, mobilized the anti-Vietnam War movement and other liberal supporters to win his party's nomination. Among the candidates he defeated were early front-runner Edmund Muskie, 1968 nominee Hubert Humphrey, governor George Wallace, and representative Shirley Chisholm.

Nixon emphasized the strong economy and his success in foreign affairs, while McGovern ran on a platform calling for an immediate end to the Vietnam War and the institution of a guaranteed minimum income. Nixon maintained a large lead in polling. Separately, Nixon's reelection committee broke into the Watergate complex to wiretap the Democratic National Committee's headquarters as part of the Watergate scandal. McGovern's general election campaign was damaged early on by revelations from his running mate Thomas Eagleton, as well as the perception that McGovern's platform was radical. Eagleton had undergone electroconvulsive therapy as a treatment for depression, and he was replaced by Sargent Shriver after only nineteen days on the ticket.

Nixon won the election in a landslide victory, taking 60.7% of the popular vote and carrying 49 states and becoming the first Republican to sweep the South, whereas McGovern took just 37.5% of the popular vote. Meanwhile, this marked the last time the Republican nominee carried Minnesota in a presidential election. This also made Nixon the first two-term vice president to be elected president twice. The 1972 election was the first since the ratification of the 26th Amendment, which lowered the voting age from 21 to 18, further expanding the electorate.

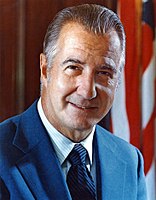

Both Nixon and his vice president Spiro Agnew would resign from office within two years of the election. The latter resigned due to a bribery scandal in October 1973, and the former resigned in the face of likely impeachment and conviction as a result of the Watergate scandal in August 1974. Republican House Minority Leader Gerald Ford replaced Agnew as vice president in December 1973, and thus, replaced Nixon as president in August 1974. Ford remains the only person in American history to become president without winning an election for president or vice president.

Despite this election delivering Nixon's greatest electoral triumph, Nixon later wrote in his memoirs that "it was one of the most frustrating and in many ways the least satisfying of all".[2]

Republican candidates:

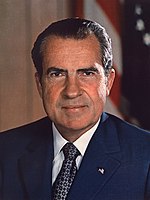

- Richard Nixon, President of the United States from California

- Pete McCloskey, Representative from California

- John M. Ashbrook, Representative from Ohio

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Richard Nixon | Spiro Agnew | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 37th President of the United States (1969–1974) |

39th Vice President of the United States (1969–1973) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Campaign | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Primaries

Nixon was a popular incumbent president in 1972, as he was credited with opening the People's Republic of China as a result of his visit that year, and achieving détente with the Soviet Union. Polls showed that Nixon held a strong lead in the Republican primaries. He was challenged by two candidates: liberal Pete McCloskey from California, and conservative John Ashbrook from Ohio. McCloskey ran as an anti-war candidate, while Ashbrook opposed Nixon's détente policies towards China and the Soviet Union. In the New Hampshire primary, McCloskey garnered 19.8% of the vote to Nixon's 67.6%, with Ashbrook receiving 9.7%.[3] Nixon won 1323 of the 1324 delegates to the Republican convention, with McCloskey receiving the vote of one delegate from New Mexico. Vice President Spiro Agnew was re-nominated by acclamation; while both the party's moderate wing and Nixon himself had wanted to replace him with a new running-mate (the moderates favoring Nelson Rockefeller, and Nixon favoring John Connally), it was ultimately concluded that such action would incur too great a risk of losing Agnew's base of conservative supporters.

Primary results

| Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Richard M. Nixon (incumbent) | 5,378,704 | 86.9 | |

| Unpledged delegates | 317,048 | 5.1 | |

| John M. Ashbrook | 311,543 | 5.0 | |

| Paul N. McCloskey | 132,731 | 2.1 | |

| George C. Wallace | 20,472 | 0.3 | |

| "None of the names shown" | 5,350 | 0.1 | |

| Others | 22,433 | 0.4 | |

| Total votes | 6,188,281 | 100 | |

Convention

Seven members of Vietnam Veterans Against the War were brought on federal charges for conspiring to disrupt the Republican convention.[5] They were acquitted by a federal jury in Gainesville, Florida.[5]

Overall, fifteen people declared their candidacy for the Democratic Party nomination. They were:[6][7]

- George McGovern, senator from South Dakota

- Hubert Humphrey, senator from Minnesota, former vice president, and presidential nominee in 1968

- George Wallace, Governor of Alabama

- Edmund Muskie, senator from Maine, vice presidential nominee in 1968

- Eugene J. McCarthy, former senator from Minnesota

- Henry M. Jackson, senator from Washington

- Shirley Chisholm, Representative of New York's 12th congressional district

- Terry Sanford, former governor of North Carolina

- John Lindsay, Mayor of New York City

- Wilbur Mills, representative of Arkansas's 2nd congressional district

- Vance Hartke, senator from Indiana

- Fred Harris, senator from Oklahoma

- Sam Yorty, Mayor of Los Angeles

- Patsy Mink, representative of Hawaii's 2nd congressional district

- Walter Fauntroy, Delegate from Washington, D. C.

| George McGovern | Sargent Shriver | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| U.S. Senator from South Dakota (1963–1981) |

21st U.S. Ambassador to France (1968–1970) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Campaign | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Primaries

Senate Majority Whip Ted Kennedy, the youngest brother of late President John F. Kennedy and late United States Senator Robert F. Kennedy, was the favorite to win the 1972 nomination, but he announced he would not be a candidate.[8] The favorite for the Democratic nomination then became Maine Senator Ed Muskie,[9] the 1968 vice-presidential nominee.[10] Muskie's momentum collapsed just prior to the New Hampshire primary, when the so-called "Canuck letter" was published in the Manchester Union-Leader. The letter, actually a forgery from Nixon's "dirty tricks" unit, claimed that Muskie had made disparaging remarks about French-Canadians – a remark likely to injure Muskie's support among the French-American population in northern New England.[11] Subsequently, the paper published an attack on the character of Muskie's wife Jane, reporting that she drank and used off-color language during the campaign. Muskie made an emotional defense of his wife in a speech outside the newspaper's offices during a snowstorm. Though Muskie later stated that what had appeared to the press as tears were actually melted snowflakes, the press reported that Muskie broke down and cried, shattering the candidate's image as calm and reasoned.[11][12]

Nearly two years before the election, South Dakota Senator George McGovern entered the race as an anti-war, progressive candidate.[13] McGovern was able to pull together support from the anti-war movement and other grassroots support to win the nomination in a primary system he had played a significant part in designing.

On January 25, 1972, New York Representative Shirley Chisholm announced she would run, and became the first African-American woman to run for a major-party presidential nomination. Hawaii Representative Patsy Mink also announced she would run, and became the first Asian American person to run for the Democratic presidential nomination.[14]

On April 25, George McGovern won the Massachusetts primary. Two days later, journalist Robert Novak quoted a "Democratic senator", later revealed to be Thomas Eagleton, as saying: "The people don't know McGovern is for amnesty, abortion, and legalization of pot. Once middle America – Catholic middle America, in particular – finds this out, he's dead." The label stuck, and McGovern became known as the candidate of "amnesty, abortion, and acid". It became Humphrey's battle cry to stop McGovern—especially in the Nebraska primary.[15][16]

Alabama Governor George Wallace, an infamous segregationist who ran on a third-party ticket in 1968, did well in the South (winning nearly every county in the Florida primary) and among alienated and dissatisfied voters in the North.[17] What might have become a forceful campaign was cut short when Wallace was shot in an assassination attempt by Arthur Bremer on May 15. Wallace was struck by five bullets and left paralyzed from the waist down. The day after the assassination attempt, Wallace won the Michigan and Maryland primaries, but the shooting effectively ended his campaign, and he pulled out in July.

In the end, McGovern won the nomination by winning primaries through grassroots support, in spite of establishment opposition. McGovern had led a commission to re-design the Democratic nomination system after the divisive nomination struggle and convention of 1968. However, the new rules angered many prominent Democrats whose influence was marginalized, and those politicians refused to support McGovern's campaign (some even supporting Nixon instead), leaving the McGovern campaign at a significant disadvantage in funding, compared to Nixon. Some of the principles of the McGovern Commission have lasted throughout every subsequent nomination contest, but the Hunt Commission instituted the selection of superdelegates a decade later, in order to reduce the nomination chances of outsiders such as McGovern and Jimmy Carter.

Primary results

| Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hubert H. Humphrey | 4,121,372 | 25.8 | |

| George S. McGovern | 4,053,451 | 25.3 | |

| George C. Wallace | 3,755,424 | 23.5 | |

| Edmund S. Muskie | 1,840,217 | 11.5 | |

| Eugene J. McCarthy | 553,955 | 3.5 | |

| Henry M. Jackson | 505,198 | 3.2 | |

| Shirley A. Chisholm | 430,703 | 2.7 | |

| James T. Sanford | 331,415 | 2.1 | |

| John V. Lindsay | 196,406 | 1.2 | |

| Sam W. Yorty | 79,446 | 0.5 | |

| Wilbur D. Mills | 37,401 | 0.2 | |

| Walter E. Fauntroy | 21,217 | 0.1 | |

| Unpledged delegates | 19,533 | 0.1 | |

| Edward M. Kennedy | 16,693 | 0.1 | |

| Rupert V. Hartke | 11,798 | 0.1 | |

| Patsy M. Mink | 8,286 | 0.1 | |

| "None of the names shown" | 6,269 | 0 | |

| Others | 5,181 | 0 | |

| Total votes | 15,993,965 | 100 | |

Notable endorsements

- Former Governor of and Secretary of Commerce W. Averell Harriman from New York[18]

- Senator Harold Hughes from Iowa[19]

- Senator Birch Bayh from Indiana[20]

- Senator Adlai Stevenson III from Illinois[21]

- Senator Mike Gravel of Alaska[22]

- Former Senator Stephen M. Young from Ohio[23]

- Governor Milton Shapp of Pennsylvania[24]

- Former Governor Michael DiSalle of Ohio[23]

- Ohio State Treasurer Gertrude W. Donahey[25]

- Astronaut John Glenn from Ohio[23]

George McGovern

- Senator Frank Church from Idaho[26]

George Wallace

- Former Governor Lester Maddox of Georgia[27]

Shirley Chisholm

- Representative Ron Dellums from California[28]

- Feminist leader and author Betty Friedan[29]

- Feminist leader, journalist, and DNC official Gloria Steinem[30]

Terry Sanford

- Former President Lyndon B. Johnson from Texas[31]

Henry M. Jackson

- Governor Jimmy Carter of Georgia[32]

1972 Democratic National Convention

Results:

- George McGovern – 1864.95

- Henry M. Jackson – 525

- George Wallace – 381.7

- Shirley Chisholm – 151.95

- Terry Sanford – 77.5

- Hubert Humphrey – 66.7

- Wilbur Mills – 33.8

- Edmund Muskie – 24.3

- Ted Kennedy – 12.7

- Sam Yorty – 10

- Wayne Hays – 5

- John Lindsay – 5

- Fred Harris – 2

- Eugene McCarthy – 2

- Walter Mondale – 2

- Ramsey Clark – 1

- Walter Fauntroy – 1

- Vance Hartke – 1

- Harold Hughes – 1

- Patsy Mink – 1

Vice presidential vote

Most polls showed McGovern running well behind incumbent President Richard Nixon, except when McGovern was paired with Massachusetts Senator Ted Kennedy. McGovern and his campaign brain trust lobbied Kennedy heavily to accept the bid to be McGovern's running mate, but he continually refused their advances, and instead suggested U.S. Representative (and House Ways and Means Committee chairman) Wilbur Mills from Arkansas and Boston Mayor Kevin White.[33] Offers were then made to Hubert Humphrey, Connecticut Senator Abraham Ribicoff, and Minnesota Senator Walter Mondale, all of whom turned it down. Finally, the vice presidential slot was offered to Senator Thomas Eagleton from Missouri, who accepted the offer.[33]

With hundreds of delegates displeased with McGovern, the vote to ratify Eagleton's candidacy was chaotic, with at least three other candidates having their names put into nomination and votes scattered over 70 candidates.[34] A grassroots attempt to displace Eagleton in favor of Texas state representative Frances Farenthold gained significant traction, though was ultimately unable to change the outcome of the vote.[35]

The vice-presidential balloting went on so long that McGovern and Eagleton were forced to begin making their acceptance speeches at around 2 am, local time.

After the convention ended, it was discovered that Eagleton had undergone psychiatric electroshock therapy for depression and had concealed this information from McGovern. A Time magazine poll taken at the time found that 77 percent of the respondents said, "Eagleton's medical record would not affect their vote." Nonetheless, the press made frequent references to his "shock therapy", and McGovern feared that this would detract from his campaign platform.[36] McGovern subsequently consulted confidentially with pre-eminent psychiatrists, including Eagleton's own doctors, who advised him that a recurrence of Eagleton's depression was possible and could endanger the country, should Eagleton become president.[37][38][39][40][41] McGovern had initially claimed that he would back Eagleton "1000 percent",[42] only to ask Eagleton to withdraw three days later. This perceived lack of conviction in sticking with his running mate was disastrous for the McGovern campaign.

McGovern later approached six prominent Democrats to run for vice president: Ted Kennedy, Edmund Muskie, Hubert Humphrey, Abraham Ribicoff, Larry O'Brien, and Reubin Askew. All six declined. Sargent Shriver, brother-in-law to John, Robert, and Ted Kennedy, former Ambassador to France, and former Director of the Peace Corps, later accepted.[43] He was officially nominated by a special session of the Democratic National Committee. By this time, McGovern's poll ratings had plunged from 41 to 24 percent.

| 1972 American Independent Party ticket | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| John G. Schmitz | Thomas J. Anderson | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| for President | for Vice President | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| U.S. Representative from California's 35th district (1970–1973) |

Magazine publisher; conservative speaker | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Campaign | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other Candidates | ||||||||

| Lester Maddox | Thomas J. Anderson | George Wallace | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lieutenant Governor of Georgia (1971–1975) Governor of Georgia (1967–1971) |

Magazine publisher; conservative speaker | Governor of Alabama (1963–1967, 1971–1979) 1968 AIP Presidential Nominee | ||||||

| Campaign | Campaign | Campaign | ||||||

| 56 votes | 24 votes | 8 votes | ||||||

The only major third party candidate in the 1972 election was conservative Republican Representative John G. Schmitz, who ran on the American Independent Party ticket (the party on whose ballot George Wallace ran in 1968). He was on the ballot in 32 states and received 1,099,482 votes. Unlike Wallace, however, he did not win a majority of votes cast in any state, and received no electoral votes, although he did finish ahead of McGovern in four of the most conservative Idaho counties.[44] Schmitz's performance in archconservative Jefferson County was the best by a third-party Presidential candidate in any free or postbellum state county since 1936 when William Lemke reached over twenty-eight percent of the vote in the North Dakota counties of Burke, Sheridan and Hettinger.[45] Schmitz was endorsed by fellow John Birch Society member Walter Brennan, who also served as finance chairman for his campaign.[46]

John Hospers and Theodora "Tonie" Nathan of the newly formed Libertarian Party were on the ballot only in Colorado and Washington, but were official write-in candidates in four others, and received 3,674 votes, winning no states. However, they did receive one Electoral College vote from Virginia from a Republican faithless elector (see below). The Libertarian vice-presidential nominee Tonie Nathan became the first Jew and the first woman in U.S. history to receive an Electoral College vote.[47]

Linda Jenness was nominated by the Socialist Workers Party, with Andrew Pulley as her running-mate. Benjamin Spock and Julius Hobson were nominated for president and vice-president, respectively, by the People's Party.

Campaign

McGovern ran on a platform of immediately ending the Vietnam War and instituting a radical guaranteed minimum incomes for the nation's poor. His campaign was harmed by his views during the primaries (which alienated many powerful Democrats), the perception that his foreign policy was too extreme, and the Eagleton debacle. With McGovern's campaign weakened by these factors, with the Republicans portraying McGovern as a radical left-wing extremist, Nixon led in the polls by large margins throughout the entire campaign. With an enormous fundraising advantage and a comfortable lead in the polls, Nixon concentrated on large rallies and focused speeches to closed, select audiences, leaving much of the retail campaigning to surrogates like Vice President Agnew. Nixon did not, by design, try to extend his coattails to Republican congressional or gubernatorial candidates, preferring to pad his own margin of victory.

Results

Nixon's percentage of the popular vote was only marginally less than Lyndon Johnson's record in the 1964 election, and his margin of victory was slightly larger. Nixon won a majority vote in 49 states, including McGovern's home state of South Dakota. Only Massachusetts and the District of Columbia voted for the challenger, resulting in an even more lopsided Electoral College tally. McGovern garnered only 37.5 percent of the national popular vote, the lowest share received by a Democratic Party nominee since John W. Davis won only 28.8 percent of the vote in the 1924 election. The only major party candidate since 1972 to receive less than 40 percent of the vote was Republican incumbent President George H. W. Bush who won 37.4 percent of the vote in the 1992 election, a race that (as in 1924) was complicated by a strong non-major-party vote.[48] Nixon received the highest share of the popular vote for a Republican in history.

Although the McGovern campaign believed that its candidate had a better chance of defeating Nixon because of the new Twenty-sixth Amendment to the United States Constitution that lowered the national voting age to 18 from 21, most of the youth vote went to Nixon.[49] This was the first election in American history in which a Republican candidate carried every single Southern state, continuing the region's transformation from a Democratic bastion into a Republican stronghold as Arkansas was carried by a Republican presidential candidate for the first time in a century. By this time, all the Southern states, except Arkansas and Texas, had been carried by a Republican in either the previous election or the one in 1964 (although Republican candidates carried Texas in 1928, 1952 and 1956). As a result of this election, Massachusetts became the only state that Nixon did not carry in any of the three presidential elections in which he was a candidate. Notably, Nixon became the first Republican to ever win two terms in the White House without carrying Massachusetts at least once, and the same feat would later be duplicated by George W. Bush who won both the 2000 and 2004 elections without winning Massachusetts either time. This presidential election was the first since 1808 in which New York did not have the largest number of electors in the Electoral College, having fallen to 41 electors vs. California's 45. Additionally, through 2020 it remains the last one in which Minnesota was carried by the Republican candidate.[50]

McGovern won a mere 130 counties, plus the District of Columbia and four county-equivalents in Alaska,[lower-alpha 2] easily the fewest counties won by any major-party presidential nominee since the advent of popular presidential elections.[51] In nineteen states, McGovern failed to carry a single county;[lower-alpha 3] he carried a mere one county-equivalent in a further nine states,[lower-alpha 4] and just two counties in a further seven.[lower-alpha 5] In contrast to Walter Mondale's narrow 1984 win in Minnesota, McGovern comfortably did win Massachusetts, but lost every other state by no less than five percentage points, as well as 45 states by more than ten percentage points – the exceptions being Massachusetts, Minnesota, Rhode Island, Wisconsin, and his home state of South Dakota. This election also made Nixon the second former vice president in American history to serve two terms back-to-back, after Thomas Jefferson in 1800 and 1804. As well as the only two-term Vice President to be elected President twice.

Since McGovern carried only one state, bumper stickers reading "Nixon 49 America 1",[52] "Don't Blame Me, I'm From Massachusetts", and "Massachusetts: The One And Only" were popular for a short time in Massachusetts.[53]

Nixon managed to win 18% of the African American vote (Gerald Ford would get 16% in 1976).[54] He also remains the only Republican in modern times to threaten the oldest extant Democratic stronghold of South Texas: this is the last election when the Republicans have won Hidalgo or Dimmit counties, the only time Republicans have won La Salle County between William McKinley in 1900 and Donald Trump in 2020, and one of only two occasions since Theodore Roosevelt in 1904[lower-alpha 6] that Republicans have gained a majority in Presidio County.[50] More significantly, the 1972 election was the most recent time several highly populous urban counties – including Cook in Illinois, Orleans in Louisiana, Hennepin in Minnesota, Cuyahoga in Ohio, Durham in North Carolina, Queens in New York, and Prince George's in Maryland – have voted Republican.[50]

The Wallace vote had also been crucial to Nixon being able to sweep the states that had narrowly held out against him in 1968 (Texas, Maryland, and West Virginia), as well as the states Wallace won himself (Arkansas, Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi, and Georgia). The pro-Wallace group of voters had only given AIP nominee John Schmitz a depressing 2.4% of its support, while 19.1% backed McGovern, and the majority 78.5% broke for Nixon.

Nixon, who became term-limited under the provisions of the Twenty-second Amendment as a result of his victory, became the first (and, as of 2023, only) presidential candidate to win a significant number of electoral votes in three presidential elections since the ratification of that Amendment. As of 2023, Nixon was the seventh of seven presidential nominees to win a significant number of electoral votes in at least three elections, the others being Thomas Jefferson, Henry Clay, Andrew Jackson, Grover Cleveland, William Jennings Bryan, and Franklin D. Roosevelt. He is the only Republican ever to do so.

The 520 electoral votes received by Nixon, added to the 301 electoral votes he received in 1968, and the 219 electoral votes he received in 1960, gave him the most total electoral votes received by any candidate who had been previously Vice President to become president (1,040) and the second largest number of electoral votes received by any candidate who was elected to the office of president behind Franklin D. Roosevelt's 1,876 total electoral votes.

| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote[55] | Electoral vote[56] |

Running mate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | Vice-presidential candidate | Home state | Electoral vote[57] | ||||

| Richard Nixon (incumbent) | Republican | California | 47,168,710 | 60.67% | 520 | Spiro T. Agnew (incumbent) | Maryland | 520 |

| George McGovern | Democratic | South Dakota | 29,173,222 | 37.52% | 17 | Sargent Shriver | Maryland | 17 |

| John G. Schmitz | American Independent | California | 1,100,896 | 1.42% | 0 | Thomas J. Anderson | Tennessee | 0 |

| Linda Jenness | Socialist Workers | Georgia | 83,380[lower-alpha 7] | 0.11% | 0 | Andrew Pulley | Illinois | 0 |

| Benjamin Spock | People's | California | 78,759 | 0.10% | 0 | Julius Hobson | District of Columbia | 0 |

| Louis Fisher | Socialist Labor | Illinois | 53,814 | 0.07% | 0 | Genevieve Gunderson | Minnesota | 0 |

| John G. Hospers | Libertarian | California | 3,674 | 0.00% | 1[lower-alpha 8][47] | Theodora Nathan | Oregon | 1[lower-alpha 9][47] |

| Other | 81,575 | 0.10% | — | Other | — | |||

| Total | 77,744,030 | 100% | 538 | 538 | ||||

| Needed to win | 270 | 270 | ||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Results by county, shaded according to winning candidate's percentage of the vote

Results by state

- Legend

| States/districts won by Nixon/Agnew | |

| States/districts won by McGovern/Shriver | |

| † | At-large results (Maine used the Congressional District Method) |

| Richard Nixon Republican |

George McGovern Democratic |

John Schmitz American Independent |

John Hospers Libertarian |

Margin | State Total | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | # | |

| Alabama | 9 | 728,701 | 72.43 | 9 | 256,923 | 25.54 | 11,918 | 1.18 | 471,778 | 46.89 | 1,006,093 | AL | |||||

| Alaska | 3 | 55,349 | 58.13 | 3 | 32,967 | 34.62 | 6,903 | 7.25 | 22,382 | 23.51 | 95,219 | AK | |||||

| Arizona | 6 | 402,812 | 61.64 | 6 | 198,540 | 30.38 | 21,208 | 3.25 | 204,272 | 31.26 | 653,505 | AZ | |||||

| Arkansas | 6 | 445,751 | 68.82 | 6 | 198,899 | 30.71 | 3,016 | 0.47 | 246,852 | 38.11 | 647,666 | AR | |||||

| California | 45 | 4,602,096 | 55.00 | 45 | 3,475,847 | 41.54 | 232,554 | 2.78 | 980 | 0.01 | 1,126,249 | 13.46 | 8,367,862 | CA | |||

| Colorado | 7 | 597,189 | 62.61 | 7 | 329,980 | 34.59 | 17,269 | 1.81 | 1,111 | 0.12 | 267,209 | 28.01 | 953,884 | CO | |||

| Connecticut | 8 | 810,763 | 58.57 | 8 | 555,498 | 40.13 | 17,239 | 1.25 | 255,265 | 18.44 | 1,384,277 | CT | |||||

| Delaware | 3 | 140,357 | 59.60 | 3 | 92,283 | 39.18 | 2,638 | 1.12 | 48,074 | 20.41 | 235,516 | DE | |||||

| D.C. | 3 | 35,226 | 21.56 | 127,627 | 78.10 | 3 | −92,401 | −56.54 | 163,421 | DC | |||||||

| Florida | 17 | 1,857,759 | 71.91 | 17 | 718,117 | 27.80 | 1,139,642 | 44.12 | 2,583,283 | FL | |||||||

| Georgia | 12 | 881,496 | 75.04 | 12 | 289,529 | 24.65 | 812 | 0.07 | 591,967 | 50.39 | 1,174,772 | GA | |||||

| Hawaii | 4 | 168,865 | 62.48 | 4 | 101,409 | 37.52 | 67,456 | 24.96 | 270,274 | HI | |||||||

| Idaho | 4 | 199,384 | 64.24 | 4 | 80,826 | 26.04 | 28,869 | 9.30 | 118,558 | 38.20 | 310,379 | ID | |||||

| Illinois | 26 | 2,788,179 | 59.03 | 26 | 1,913,472 | 40.51 | 2,471 | 0.05 | 874,707 | 18.52 | 4,723,236 | IL | |||||

| Indiana | 13 | 1,405,154 | 66.11 | 13 | 708,568 | 33.34 | 696,586 | 32.77 | 2,125,529 | IN | |||||||

| Iowa | 8 | 706,207 | 57.61 | 8 | 496,206 | 40.48 | 22,056 | 1.80 | 210,001 | 17.13 | 1,225,944 | IA | |||||

| Kansas | 7 | 619,812 | 67.66 | 7 | 270,287 | 29.50 | 21,808 | 2.38 | 349,525 | 38.15 | 916,095 | KS | |||||

| Kentucky | 9 | 676,446 | 63.37 | 9 | 371,159 | 34.77 | 17,627 | 1.65 | 305,287 | 28.60 | 1,067,499 | KY | |||||

| Louisiana | 10 | 686,852 | 65.32 | 10 | 298,142 | 28.35 | 52,099 | 4.95 | 388,710 | 36.97 | 1,051,491 | LA | |||||

| Maine † | 2 | 256,458 | 61.46 | 2 | 160,584 | 38.48 | 117 | 0.03 | 1 | 0.00 | 95,874 | 22.98 | 417,271 | ME | |||

| Maine-1 | 1 | 135,388 | 61.42 | 1 | 85,028 | 38.58 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 50,360 | 22.85 | 220,416 | ME1 | |||

| Maine-2 | 1 | 121,120 | 61.58 | 1 | 75,556 | 38.42 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown | 45,564 | 23.17 | 196,676 | ME2 | |||

| Maryland | 10 | 829,305 | 61.26 | 10 | 505,781 | 37.36 | 18,726 | 1.38 | 323,524 | 23.90 | 1,353,812 | MD | |||||

| Massachusetts | 14 | 1,112,078 | 45.23 | 1,332,540 | 54.20 | 14 | 2,877 | 0.12 | 43 | 0.00 | −220,462 | −8.97 | 2,458,756 | MA | |||

| Michigan | 21 | 1,961,721 | 56.20 | 21 | 1,459,435 | 41.81 | 63,321 | 1.81 | 502,286 | 14.39 | 3,490,325 | MI | |||||

| Minnesota | 10 | 898,269 | 51.58 | 10 | 802,346 | 46.07 | 31,407 | 1.80 | 95,923 | 5.51 | 1,741,652 | MN | |||||

| Mississippi | 7 | 505,125 | 78.20 | 7 | 126,782 | 19.63 | 11,598 | 1.80 | 378,343 | 58.57 | 645,963 | MS | |||||

| Missouri | 12 | 1,154,058 | 62.29 | 12 | 698,531 | 37.71 | 455,527 | 24.59 | 1,852,589 | MO | |||||||

| Montana | 4 | 183,976 | 57.93 | 4 | 120,197 | 37.85 | 13,430 | 4.23 | 63,779 | 20.08 | 317,603 | MT | |||||

| Nebraska | 5 | 406,298 | 70.50 | 5 | 169,991 | 29.50 | 236,307 | 41.00 | 576,289 | NE | |||||||

| Nevada | 3 | 115,750 | 63.68 | 3 | 66,016 | 36.32 | 49,734 | 27.36 | 181,766 | NV | |||||||

| New Hampshire | 4 | 213,724 | 63.98 | 4 | 116,435 | 34.86 | 3,386 | 1.01 | 97,289 | 29.12 | 334,055 | NH | |||||

| New Jersey | 17 | 1,845,502 | 61.57 | 17 | 1,102,211 | 36.77 | 34,378 | 1.15 | 743,291 | 24.80 | 2,997,229 | NJ | |||||

| New Mexico | 4 | 235,606 | 61.05 | 4 | 141,084 | 36.56 | 8,767 | 2.27 | 94,522 | 24.49 | 385,931 | NM | |||||

| New York | 41 | 4,192,778 | 58.54 | 41 | 2,951,084 | 41.21 | 1,241,694 | 17.34 | 7,161,830 | NY | |||||||

| North Carolina | 13 | 1,054,889 | 69.46 | 13 | 438,705 | 28.89 | 25,018 | 1.65 | 616,184 | 40.58 | 1,518,612 | NC | |||||

| North Dakota | 3 | 174,109 | 62.07 | 3 | 100,384 | 35.79 | 5,646 | 2.01 | 73,725 | 26.28 | 280,514 | ND | |||||

| Ohio | 25 | 2,441,827 | 59.63 | 25 | 1,558,889 | 38.07 | 80,067 | 1.96 | 882,938 | 21.56 | 4,094,787 | OH | |||||

| Oklahoma | 8 | 759,025 | 73.70 | 8 | 247,147 | 24.00 | 23,728 | 2.30 | 511,878 | 49.70 | 1,029,900 | OK | |||||

| Oregon | 6 | 486,686 | 52.45 | 6 | 392,760 | 42.33 | 46,211 | 4.98 | 93,926 | 10.12 | 927,946 | OR | |||||

| Pennsylvania | 27 | 2,714,521 | 59.11 | 27 | 1,796,951 | 39.13 | 70,593 | 1.54 | 917,570 | 19.98 | 4,592,105 | PA | |||||

| Rhode Island | 4 | 220,383 | 53.00 | 4 | 194,645 | 46.81 | 25 | 0.01 | 2 | 0.00 | 25,738 | 6.19 | 415,808 | RI | |||

| South Carolina | 8 | 478,427 | 70.58 | 8 | 189,270 | 27.92 | 10,166 | 1.50 | 289,157 | 42.66 | 677,880 | SC | |||||

| South Dakota | 4 | 166,476 | 54.15 | 4 | 139,945 | 45.52 | 26,531 | 8.63 | 307,415 | SD | |||||||

| Tennessee | 10 | 813,147 | 67.70 | 10 | 357,293 | 29.75 | 30,373 | 2.53 | 455,854 | 37.95 | 1,201,182 | TN | |||||

| Texas | 26 | 2,298,896 | 66.20 | 26 | 1,154,291 | 33.24 | 7,098 | 0.20 | 1,144,605 | 32.96 | 3,472,714 | TX | |||||

| Utah | 4 | 323,643 | 67.64 | 4 | 126,284 | 26.39 | 28,549 | 5.97 | 197,359 | 41.25 | 478,476 | UT | |||||

| Vermont | 3 | 117,149 | 62.66 | 3 | 68,174 | 36.47 | 48,975 | 26.20 | 186,947 | VT | |||||||

| Virginia | 12 | 988,493 | 67.84 | 11 | 438,887 | 30.12 | 19,721 | 1.35 | 1 | 549,606 | 37.72 | 1,457,019 | VA | ||||

| Washington | 9 | 837,135 | 56.92 | 9 | 568,334 | 38.64 | 58,906 | 4.00 | 1,537 | 0.10 | 268,801 | 18.28 | 1,470,847 | WA | |||

| West Virginia | 6 | 484,964 | 63.61 | 6 | 277,435 | 36.39 | 207,529 | 27.22 | 762,399 | WV | |||||||

| Wisconsin | 11 | 989,430 | 53.40 | 11 | 810,174 | 43.72 | 47,525 | 2.56 | 179,256 | 9.67 | 1,852,890 | WI | |||||

| Wyoming | 3 | 100,464 | 69.01 | 3 | 44,358 | 30.47 | 748 | 0.51 | 56,106 | 38.54 | 145,570 | WY | |||||

| TOTALS: | 538 | 47,168,710 | 60.67 | 520 | 29,173,222 | 37.52 | 17 | 1,100,868 | 1.42 | 0 | 3,674 | 0.00 | 1 | 17,995,488 | 23.15 | 77,744,027 | US |

For the first time since 1828, Maine allowed its electoral votes to be split between candidates. Two electoral votes were awarded to the winner of the statewide race and one electoral vote to the winner of each congressional district. This was the first time the Congressional District Method had been used since Michigan used it in 1892. Nixon won all four votes.[60]

States that flipped from Democratic to Republican

States that flipped from American Independent to Republican

Close states

States where margin of victory was more than 5 percentage points, but less than 10 percentage points (43 electoral votes):

|

Tipping point states:

- Ohio, 21.56% (882,938 votes) (tipping point for a Nixon victory)

- Maine-1, 22.85% (50,360 votes) (tipping point for a McGovern victory)[61]

Statistics

Counties with highest percentage of the vote (Republican)

- Dade County, Georgia 93.45%

- Glascock County, Georgia 93.38%

- George County, Mississippi 92.90%

- Holmes County, Florida 92.51%

- Smith County, Mississippi 92.35%

Counties with highest percentage of the vote (Democratic)

- Duval County, Texas 85.68%

- Washington, D. C. 78.10%

- Shannon County, South Dakota 77.34%

- Greene County, Alabama 68.32%

- Charles City County, Virginia 67.84%

Counties with highest percentage of the vote (Other)

- Jefferson County, Idaho 27.51%

- Lemhi County, Idaho 19.77%

- Fremont County, Idaho 19.32%

- Bonneville County, Idaho 18.97%

- Madison County, Idaho 17.04%

Nixon won 36 percent of the Democratic vote, according to an exit poll conducted for CBS News by George Fine Research, Inc.[62] This represents more than twice the percentage of voters who typically defect from their party in presidential elections. Nixon also became the first Republican presidential candidate in American history to win the Roman Catholic vote (53–46), and the first in recent history to win the blue-collar vote, which he won by a 5-to-4 margin. McGovern narrowly won the union vote (50–48), though this difference was within the survey's margin of error of 2 percentage points. McGovern also narrowly won the youth vote (i. e., those aged 18 to 24) 52–46, a narrower margin than many of his strategists had predicted. Early on, the McGovern campaign also significantly over-estimated the number of young people who would vote in the election: They predicted that 18 million would have voted in total, but exit polls indicate that the actual number was about 12 million. McGovern did win comfortably among both African-American and Jewish voters, but by somewhat smaller margins than usual for a Democratic candidate.[62] McGovern won the African American vote by 87% to Nixon's 13%.[63]

On June 17, 1972, five months before election day, five men broke into the Democratic National Committee headquarters at the Watergate hotel in Washington, D. C.; the resulting investigation led to the revelation of attempted cover-ups of the break-in within the Nixon administration. What became known as the Watergate scandal eroded President Nixon's public and political support in his second term, and he resigned on August 9, 1974, in the face of probable impeachment by the House of Representatives and removal from office by the Senate.

As part of the continuing Watergate investigation in 1974–1975, federal prosecutors offered companies that had given illegal campaign contributions to President Nixon's re-election campaign lenient sentences if they came forward.[64] Many companies complied, including Northrop Grumman, 3M, American Airlines, and Braniff Airlines.[64] By 1976, prosecutors had convicted 18 American corporations of contributing illegally to Nixon's campaign.[64]

Despite this election delivering Nixon's greatest electoral triumph, Nixon later wrote in his memoirs that "it was one of the most frustrating and in many ways the least satisfying of all".[65]

- 1972 United States House of Representatives elections

- 1972 United States Senate elections

- 1972 United States gubernatorial elections

- George McGovern 1972 presidential campaign

- Second inauguration of Richard Nixon

- Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail '72, a collection of articles by Hunter S. Thompson on the subject of the election, focusing on the McGovern campaign.

- These were North Slope Borough, plus Bethel, Kusilvak and Hoonah-Angoon Census Areas

- McGovern failed to carry a single county in Arkansas, Connecticut, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, Nebraska, Nevada, New Jersey, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Utah, Vermont or Wyoming

- McGovern carried only one county-equivalent in Arizona (Greenlee), Illinois (Jackson), Louisiana (West Feliciana Parish), Maine (Androscoggin), Maryland (Baltimore), North Dakota (Rolette), Pennsylvania (Philadelphia), Virginia (Charles City), and West Virginia (Logan)

- McGovern carried just two counties in Colorado, Missouri, Montana, New Mexico, North Carolina, Ohio and Washington State

- Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1952 also obtained a plurality in Presidio County

- In Arizona, Pima and Yavapai counties had an unusually formatted ballot that led voters to believe they could vote for a major party presidential candidate and simultaneously vote the six individual Socialist Workers Party presidential electors. Technically, these were overvotes, and should not have counted for either the major party candidates or the Socialist Workers Party electors. Within two days of the election, the Attorney General and Pima County Attorney had agreed that all votes should count. The Socialist Workers Party had not qualified as a party, and thus did not have a presidential candidate. In the official state canvass, votes for Nixon, McGovern, or Schmitz, are shown as being for the presidential candidate, the party, and the elector slate of the party; while those for the Socialist Worker Party elector candidates were for those candidates only. In the view of the Secretary of State, the votes were not for Linda Jenness. Some tabulations count the votes for Jenness. Historically, presidential candidate names did not appear on ballots, and voters voted directly for the electors. Nonetheless, votes for the electors are attributed to the presidential candidate. Counting the votes in Arizona for Jenness is consistent with this practice. Because of the confusing ballots, Socialist Workers Party electors received votes on about 21 percent and 8 percent of ballots in Pima and Yavapai, respectively. 30,579 of the party's 30,945 Arizona votes are from those two counties.[58]

- A Virginia faithless elector, Roger MacBride, though pledged to vote for Richard Nixon and Spiro Agnew, instead voted for Libertarian candidates John Hospers and Theodora "Tonie" Nathan.

- A Virginia faithless elector, Roger MacBride, though pledged to vote for Richard Nixon and Spiro Agnew, instead voted for Libertarian candidates John Hospers and Theodora "Tonie" Nathan.

- "National General Election VEP Turnout Rates, 1789-Present". United States Election Project. CQ Press. Archived from the original on July 25, 2014. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- Emig, David (November 7, 2009). "My Morris Moment »". Archived from the original on April 18, 2023. Retrieved March 29, 2021.

- "New Hampshire Primary historical past election results. 2008 Democrat & Republican past results. John McCain, Hillary Clinton winners". Primarynewhampshire.com. Archived from the original on July 15, 2011. Retrieved August 17, 2014.

- Kalb, Deborah, ed. (2010). Guide to U.S. Elections (6th ed.). Washington, DC: CQ Press. p. 415. ISBN 9781604265361.

- Frum, David (2000). How We Got Here: The '70s. New York, New York: Basic Books. p. 52. ISBN 0-465-04195-7.

- "CQ Almanac Online Edition". Library.cqpress.com. Archived from the original on June 8, 2020. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- "Hawai'i, nation lose "a powerful voice" | The Honolulu Advertiser | Hawaii's Newspaper". The Honolulu Advertiser. Archived from the original on December 19, 2019. Retrieved August 17, 2016.

- Jack Anderson (June 4, 1971). "Don't count out Ted Kennedy". The Free Lance–Star. Archived from the original on February 5, 2021. Retrieved March 16, 2012.

- Frum, David (2000). How We Got Here: The '70s. New York, New York: Basic Books. p. 298. ISBN 0-465-04195-7.

- "Muskie, Edmund Sixtus, (1914–1996)". United States Congress. Archived from the original on December 5, 2010. Retrieved March 16, 2012.

- Mitchell, Robert (February 9, 2020). "The Democrat who cried (maybe) in New Hampshire and lost the presidential nomination". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 29, 2020. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- "REMEMBERING ED MUSKIE". March 26, 1996. Archived from the original on April 27, 1999.

- R. W. Apple, Jr. (January 18, 1971). "McGovern Enters '72 Race, Pledging Troop Withdrawal" (fee required). The New York Times. p. 1. Archived from the original on June 8, 2020. Retrieved March 16, 2012.

- Jo Freeman (February 2005). "Shirley Chisholm's 1972 Presidential Campaign". University of Illinois at Chicago Women's History Project. Archived from the original on January 26, 2015.

- Robert D. Novak (2008). The Prince of Darkness: 50 Years Reporting in Washington. Random House Digital, Inc. p. 225. ISBN 9781400052004. Archived from the original on April 18, 2023. Retrieved November 20, 2015.

- Nancy L. Cohen (2012). Delirium: The Politics of Sex in America. Counterpoint Press. pp. 37–38. ISBN 9781619020689.

- The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. "United States presidential election of 1972". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on June 5, 2020. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- Byrd, Lee (April 28, 1972). "Bland, Crybaby Roles Cost Muskie His Lead". Lansing State Journal. p. 1. Archived from the original on May 13, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

But of likely greater impediment was the sheer number of those involved, the many "senior advisors" like Clark Clifford and W. Averell Harriman and Luther B. Hodges, and the 19 senators, 34 congressmen and nine governors who had publicly enorsed Muskie.

- Risser, James (June 9, 1972). "Hughes Stands By Muskie". The Des Moines Register. p. 5. Archived from the original on May 13, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

Hughes has spent much of this week helping Muskie, whom Hughes endorsed early this year as the candidate most likely to unify the party and defeat President Nixon in November.

- "Bayh Endorses Sen. Muskie". The Logansport Press. UPI. March 17, 1972. p. 7. Archived from the original on May 13, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- "Adlai Stevenson III Endorses Sen. Muskie". Tampa Bay Times. UPI. January 11, 1972. p. 17. Archived from the original on May 13, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- "More Muskie Support". New York Times. January 15, 1972. Retrieved September 27, 2008.

- "Sticking by Muskie, Gilligan declares". The Cincinnati Post. April 27, 1972. p. 24. Archived from the original on May 13, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- "News Capsule: In the nation". The Baltimore Sun. January 26, 1972. p. 2. Archived from the original on May 13, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

Gov. Milton Shapp of Pennsylvania endorsed Senator Edmund S. Muskie, dealing a sharp blow to Senator Hubert H. Humphrey's presidential ambitions.

- "Muskie, HHH calling in Ohio". The Journal Herald. Associated Press. January 12, 1972. p. 12. Archived from the original on May 13, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- "McGovern Picking Second V.P. Candidate Same Way He Picked First". Ironwood Daily Globe. August 3, 1972. p. 11. Archived from the original on May 13, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- "Maddox Against Demo Nominees". The Knoxville News-Sentinel. July 14, 1972. p. 10. Archived from the original on May 13, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

Maddox, a booster of fellow Democrat Alabama Gov. George Wallace, said Thursday it may be best to turn the present party "over to the promoters of anarchy, Socialism and Communism" and form what he called a New Democratic Party of the People.

- ""Catalyst for Change": The 1972 Presidential Campaign of Representative Shirley Chisholm". History, Art & Archives of the United States House of Representatives. September 14, 2020. Archived from the original on May 13, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- Friedan, Betty (August 1, 2006). Life So Far: A Memoir – Google Books. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-9986-2. Archived from the original on April 18, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2010.

- "POV – Chisholm '72 . Video: Gloria Steinem reflects on Chisholm's legacy". PBS. Archived from the original on June 16, 2010. Retrieved May 28, 2010.

- Covington, Howard E.; Ellis, Marion A. (1999). Terry Sanford: politics, progress ... – Google Books. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-2356-3. Archived from the original on April 18, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2010.

- "Convention Briefs: Endorses Jackson". Wisconsin State Journal. July 12, 1972. p. 40. Archived from the original on May 13, 2022. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

Georgia Gov. Jimmy Carter endorsed Sen. Henry Jackson of Washington for the Democratic presidential nomination Tuesday and said he would nominate Jackson at the convention tonight.

- "Introducing... the McGovern Machine". Time Magazine. July 24, 1972. Archived from the original on August 9, 2014. Retrieved September 7, 2008.

- "All The Votes...Really". All Politics. CNN. Archived from the original on April 24, 2009. Retrieved May 28, 2010.

- "A Guide to the Frances Tarlton Farenthold Papers, 1913–2013". Texas Archival Resources Online. Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin. Archived from the original on December 31, 2016.

- Garofoli, Joe (March 26, 2008). "Obama bounces back – speech seemed to help". SFGATE. Archived from the original on May 25, 2011. Retrieved May 28, 2010.

- McGovern, George S., Grassroots: The Autobiography of George McGovern, New York: Random House, 1977, pp. 214–215

- McGovern, George S., Terry: My Daughter's Life-and-Death Struggle with Alcoholism, New York: Random House, 1996, pp. 97

- Marano, Richard Michael, Vote Your Conscience: The Last Campaign of George McGovern, Praeger Publishers, 2003, pp. 7

- The Washington Post, "George McGovern & the Coldest Plunge", Paul Hendrickson, September 28, 1983

- The New York Times, "'Trashing' Candidates" (op-ed), George McGovern, May 11, 1983

- "'I'm Behind Him 1000%'". Observer.com. July 21, 2016.

- Liebovich, Louis (2003). Richard Nixon, Watergate, and the Press: A Historical Retrospective. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 53. ISBN 9780275979157.

- Menendez, Albert J.; The Geography of Presidential Elections in the United States, 1868–2004, p. 100 ISBN 0786422173

- Scammon, Richard M. (compiler); America at the Polls: A Handbook of Presidential Election Statistics 1920–1964; pp. 339, 343 ISBN 0405077114

- Actor to Aid Schmitz; The New York Times, August 9, 1972

- "Libertarians trying to escape obscurity". Eugene Register-Guard. Associated Press. December 30, 1973. Archived from the original on August 26, 2021. Retrieved July 30, 2012.

- Feinman, Ronald (September 2, 2016). "Donald Trump Could Be On Way To Worst Major Party Candidate Popular Vote Percentage Since William Howard Taft In 1912 And John W. Davis In 1924!". The Progressive Professor. Archived from the original on December 20, 2019. Retrieved November 7, 2019.

- Jesse Walker (July 2008). "The Age of Nixon: Rick Perlstein on the left, the right, the '60s, and the illusion of consensus". Reason. Archived from the original on July 18, 2013. Retrieved July 27, 2013.

- Sullivan, Robert David; 'How the Red and Blue Map Evolved Over the Past Century' Archived November 16, 2016, at the Wayback Machine; America Magazine in The National Catholic Review; June 29, 2016

- Menendez, Albert J.; The Geography of Presidential Elections in the United States, 1868–2004, p. 98 ISBN 0786422173

- "New York Intelligencer". New York. Vol. 6, no. 35. New York Media, LLC. August 27, 1973. p. 57. Archived from the original on April 18, 2023. Retrieved March 16, 2019.

- Lukas, J. Anthony (January 14, 1973). "As Massachusetts went—". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 17, 2019. Retrieved March 16, 2019.

- "Exit Polls – Election Results 2008". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 23, 2020. Retrieved May 11, 2020.

- Leip, David. "1972 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved August 7, 2005.

- "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved August 7, 2005.

- "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved August 7, 2005.

- Seeley, John (November 22, 2000). "Early and Often". LA Weekly. Retrieved April 10, 2021.

- "1972 Presidential General Election Data — National". Archived from the original on February 1, 2020. Retrieved March 18, 2013.

- Barone, Michael; Matthews, Douglas; Ujifusa, Grant (1973). The Almanac of American Politics, 1974. Gambit Publications.

- Leip, David "How close were U.S. Presidential Elections?", Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved: January 24, 2013.

- Rosenthal, Jack (November 9, 1972). "Desertion Rate Doubles". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 29, 2019. Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- "Survey Reports McGovern Got 87% of the Black Vote". The New York Times. November 12, 1972. Archived from the original on February 8, 2023. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- Frum, David (2000). How We Got Here: The '70s. New York, New York: Basic Books. p. 31. ISBN 0-465-04195-7.

- Emig, David (November 7, 2009). "My Morris Moment »". Archived from the original on April 18, 2023. Retrieved March 29, 2021.

- Alexander, Herbert E. Financing the 1972 Election (1976) online

- Giglio, James N. (2009). "The Eagleton Affair: Thomas Eagleton, George McGovern, and the 1972 Vice Presidential Nomination". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 39 (4): 647–676. doi:10.1111/j.1741-5705.2009.03731.x.

- Graebner, Norman A. (1973). "Presidential Politics in a Divided America: 1972". Australian Journal of Politics and History. 19 (1): 28–47. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8497.1973.tb00722.x.

- Hofstetter, C. Richard; Zukin, Cliff (1979). "TV Network News and Advertising in the Nixon and McGovern Campaigns". Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly. 56 (1): 106–152. doi:10.1177/107769907905600117. S2CID 144048423.

- Hofstetter, C. Richard. Bias in the news: Network television coverage of the 1972 election campaign (Ohio State University Press, 1976) online

- Johnstone, Andrew, and Andrew Priest, eds. US Presidential Elections and Foreign Policy: Candidates, Campaigns, and Global Politics from FDR to Bill Clinton (2017) pp 203–228. online

- Miller, Arthur H., et al. "A majority party in disarray: Policy polarization in the 1972 election." American Political Science Review 70.3 (1976): 753-778; widely cited; online

- Nicholas, H. G. (1973). "The 1972 Elections". Journal of American Studies. 7 (1): 1–15. doi:10.1017/S0021875800012585. S2CID 145606732.

- Perry, James M. Us & them: how the press covered the 1972 election (1973) online

- Simons, Herbert W., James W. Chesebro, and C. Jack Orr. "A movement perspective on the 1972 presidential election." Quarterly Journal of Speech 59.2 (1973): 168-179. online Archived September 23, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- Trent, Judith S., and Jimmie D. Trent. "The rhetoric of the challenger: George Stanley McGovern." Communication Studies 25.1 (1974): 11-18.

- White, Theodore H. (1973). The Making of the President, 1972. New York: Atheneum. ISBN 0-689-10553-3.

Primary sources

- Chester, Edward W. (1977). A guide to political platforms.

- Porter, Kirk H. and Donald Bruce Johnson, eds. National party platforms, 1840–1972 (1973)

- The Election Wall's 1972 Election Video Page

- 1972 popular vote by counties

- 1972 popular vote by states

- 1972 popular vote by states (with bar graphs)

- Campaign commercials from the 1972 election

- C-SPAN segment on 1972 campaign commercials

- C-SPAN segment on the "Eagleton Affair"

- Election of 1972 in Counting the Votes