Vorstenlanden

Vorstenlanden

Four native states on Java, Dutch East Indies

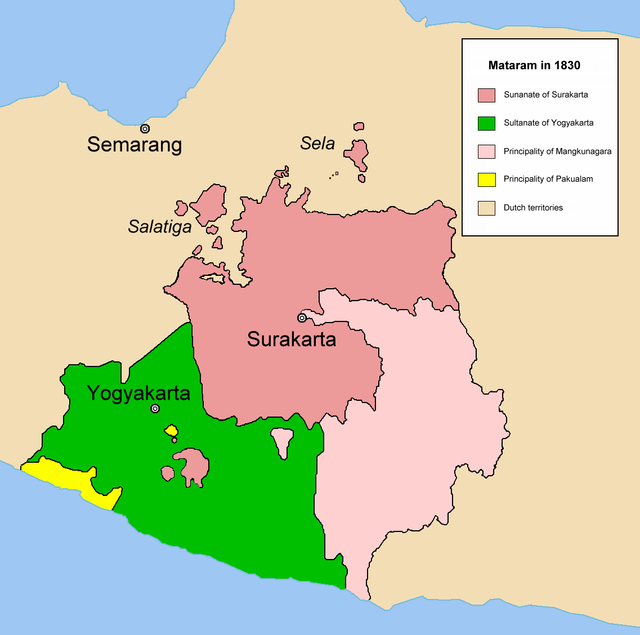

The Vorstenlanden[1] (Dutch for 'princely lands' or 'princely states', Japanese: 公地, Hepburn: kōchi, Nihon-shiki/Kunrei-shiki: kooti, Indonesian: wilayah kepangeranan, Javanese: ꧋ꦥꦿꦗꦏꦼꦗꦮꦺꦤ꧀, praja kejawen) were four native, princely states on the island of Java in the colonial Dutch East Indies. They were nominally self-governing vassals under suzerainty of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Their political autonomy however became increasingly constrained by severe treaties and settlements. Two of these continue to exist as a princely territory within the current independent republic of Indonesia.

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2018) |

The four Javanese princely states were:

- Surakarta, a sunanate to the north

- Yogyakarta, the sultanate to the south

- Mangkunegaran, a duchy to the east

- Pakualaman, a small duchy largely enclosed within the area of the Sultanate of Yogyakarta

These princely territories were successor states to the Mataram Sultanate and originated in civil wars and wars of succession within the Javanese nobility. The susuhunan of Surakarta represented the direct line of succession; the other three rulers represented cadet branches.