Ostracoderm

Ostracoderm

Armored jawless fish of the Paleozoic

Ostracoderms (lit. 'shell-skins') are the armored jawless fish of the Paleozoic Era. The term does not often appear in classifications today because it is paraphyletic (excluding jawed fishes) (may also be polyphyletic if anaspids are closer to cyclostomes) and thus does not correspond to one evolutionary lineage.[1] However, the term is still used as an informal way of loosely grouping together the armored jawless fishes.

An innovation of ostracoderms was the use of gills not for feeding, but exclusively for respiration. Earlier chordates with gill precursors used them for both respiration and feeding.[2] Ostracoderms had separate pharyngeal gill pouches along the side of the head, which were permanently open with no protective operculum. Unlike invertebrates that use ciliated motion to move food, ostracoderms used their muscular pharynx to create a suction that pulled small and slow-moving prey into their mouths.

Swiss anatomist Louis Agassiz received some fossils of bony armored fish from Scotland in the 1830s. He had difficulty classifying them, as they did not resemble any living creature. He compared them at first with extant armored fish such as catfish and sturgeon, but later realized that they lacked movable jaws. Hence, he classified them in 1844 as a new group, named "ostracoderms" to mean 'shell-skinned' (from Greek ὄστρακον óstrakon + δέρμα dérma).[3]

Ostracoderms have heads covered with a bony shield. They are among the earliest creatures with bony heads. The microscopic layers of that shield appear to evolutionary biologists, "like they are composed of little tooth-like structures."[4] Neil Shubin writes: "Cut the bone of the [ostracoderm] skull open…pop it under a microscope and…you find virtually the same structure as in our teeth. There is a layer of enamel and even a layer of pulp. The whole shield is made up of thousands of small teeth fused together. This bony skull--one of the earliest in the fossil record--is made entirely of little teeth. Teeth originally arose to bite creatures (see Conodonts); later a version of teeth was used in a new way to protect them."[4]

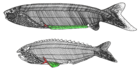

Ostracoderms existed in two major groups, the more primitive heterostracans and the cephalaspids. The cephalaspids were more advanced than the heterostracans in that they had lateral stabilizers for more control of their swimming.

It was long assumed that pteraspidomorphs and thelodonts were the only ostracoderms with paired nostrils, while the other groups have just a single median nostril. It has since been revealed that even if galeaspidans have just one external opening, it has two internal nasal organs.[5][6]

After the appearance of jawed fish (placoderms, acanthodians, sharks, etc.) about 420 million years ago, most ostracoderm species underwent a decline, and the last ostracoderms became extinct at the end of the Devonian period. More recent research indicates that fish with jaws had far less to do with the extinction of the ostracoderms than previously assumed, as they coexisted without noticeable decline for about 30 million years.[7]

The Subclass Ostracodermi has been placed in the division Agnatha along with the extant Subclass Cyclostomata, which includes lampreys and hagfishes.