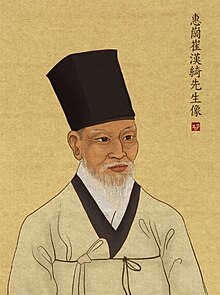

Choe_Han-gi

Choe Han-gi

Korean Confucian philosopher (1803–1877)

Choe Han-gi (Korean: 최한기; 1803–1877) was a Korean Confucian scholar and philosopher.[1][2][3][4][5] He is known for integrating Eastern philosophy with Western science in pre-industrial Korea.[6][7]

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Korean. (October 2022) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Choe Han-gi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 26 October 1803 |

| Died | 1877 (aged 73–74)[disputed – discuss] Hanseong, Joseon |

| Era | 19th-century philosophy |

| Region | Korean Confucianism |

| Korean name | |

| Hangul | 최한기 |

| Hanja | |

| Revised Romanization | Choe Hangi |

| McCune–Reischauer | Ch'oe Han'gi |

| Art name | |

| Hangul | 혜강 |

| Hanja | |

| Revised Romanization | Hyegang |

| McCune–Reischauer | Hyegang |

| Courtesy name | |

| Hangul | 운로 |

| Hanja | |

| Revised Romanization | Unno |

| McCune–Reischauer | Unno |

His art name was Hyegang (혜강), and according to some sources, it is mentioned that he also used Paedong (패동).[8][5][6]

Hyegang was born in Gaeseong (Kaesŏng), 150 kilometres (90 mi) northwest of Seoul, in the Joseon Kingdom.[1][6] His father was Choe Chihyeon of the Saknyeong Choe family, and his mother was a daughter of Han Kyŏng-ni of the Cheongju Han family.[1][8] Hyegang was adopted by his uncle Hyegang Gwanghyeon sometime after his birth.[1][8]

His foster father and uncle, a bureaucrat, took him into his care after his father passed away when he was ten.[1] Hyegang passed the saengwon examination, a civil service examination and in 1849 and later received the post as a Civil Servant.[1]

Han Kyŏng-ni, his maternal grandfather, and Kim Hŏn-gi (1774–1842) were popular Confucian scholars in Gaeseong (Kaesŏng), where Hyegang spent his childhood and are reported to have been his mentors.[2][8]

Hyegang was a Confucian philosopher, and despite being isolated for rejecting neo-Confucian morality, his grasp on Western science and integrating it with the intellectual context of East Asia is considered noteworthy.[1][2] His rejection of the classic Neo-Confucian perspective on morality was based on his understanding that ethical norms were based on, and derivable from, laws of nature.[4][9]

Hyegang sought to examine and explain nature, humanity, and society through his concept of Qi or Gi, and he is often referred to as a Qi philosopher who systematically understands and explains the world using the concept of Qi.[1][3][4]

Hyegang was raised as a Confucian philosopher, not a scientist. He spent his life establishing his own version of a perfect Confucian philosophy and studied Western science to support Qi's absolute principle.[2][9] His study of Western science was no more than the product of his need for philosophical invention. The practice of Western science was not something a Confucian philosopher in nineteenth-century Korea could fully accept and understand, so he instead worked on creating a theory that would integrate modern science with the philosophy of Qi.[2][3][9]

Hyegang accepted experimental and mathematical proficiency in Western science but did not consider it to be superior to Confucian natural philosophy and criticized Newtonian mechanics for its lack of understanding of the pseudoscience of Qi (氣), which he believed, as a Confucian philosopher, to be the ultimate substance, and also for the lack of an explanation of the origin of gravity.[1][2][3] Hyegang's interest in astronomy and heavenly bodies led him to read and interpret Newtonian mechanics and present arguments for and against it.[2] He also refused to believe Newton's acknowledgment of an omnipotent god who is the creator of everything, and all matter and non-matter following his rules.[3]

He appreciated the facts and theories of Western science with which he constructed a philosophy that realized the true nature of Qi. He used resources from Western science and Confucian natural philosophy to create a new philosophy called the Study of Qi or Kihak 氣學 (1857) and proposed new mechanics to correct the ones he found in Newton's work.[2][3][5]

Hyegang used Chinese translations of Western science and mathematics to develop the principles of the nature of Qi and proposed the Qi globe theory, kiryunsŏl 氣輪説, to replace Newtonian mechanics. He argued that Newtonian mechanics was more inclined toward mathematics and neglected the true nature of Qi and that all the problems and theories that were unresolved in the West at the time could be solved by the mechanism of Qi globes.[1][2][3]

Although Western sciences were well advanced in mathematical description, the most necessary goal of mechanics, in Hyegang's view, was the causal mechanism of phenomena based on the interaction of Qi globes.[2][3] In one of his most notable works, called Kihak 氣學, or The Study of Qi on the Mechanics of the Qi Globe, Hyegang provided Qi globes with the forces of attraction and repulsion using the Western view of electricity and electromagnetism.[2][3]

Hyegang's early and broad knowledge of Western science, compared to other Koreans of the time, has been highly appreciated by modern researchers.[2][3]

Hyegang is said to have been an avid reader and, according to sources, chose to remain in Seoul because it was the easiest place to increase his collection and knowledge from different parts of the world.[1][2][4]

He died in 1877 at the age of 75.[3][disputed – discuss] Seventeen years later, he received the posthumous post of Daesaheon Seonggyun Jeju. He was buried in the Nokbunri neighborhood of Seoul, today's Nokbeon-dong. Hyegang's grave was later relocated to Gaeseong, where his ancestors were buried.[1]

Hyegang wrote more than a thousand chapters in various fields, including orthodox Confucianism, social reform, agriculture, astronomy, mathematics, and medicine. The collection of his work was restored in the 20th century and has been expanded thrice since 1970.[2][8] Sŏnggyun'gwan University Press, Seoul, also published a five-volume photographic reproduction in 2002 called Expanded Collection of Cheo Han-gi's Writings.[2]

His writings were based on traditional Confucian philosophy and Western science. The Tantian 談天, also known as Conservations about the Sky, was Hyegang's primary source on modern astronomy and Newtonian mechanics.[2]

In Chucheuk-ron 推測錄, Documents on Inference, published in 1836, Hyegang collected many observational and experimental proofs supporting the physical substratum of Qi, while in books such as Kihak 氣學 (Study of Qi, 1857), Unhwa ch'ŭkhŏm 運化測驗 (1860) and Sŏnggi unhwa (1867), he frequently emphasized that Qi is incessantly active.[2][5]

In Chigu chŏnyo or Jigujeonyo, Hyegang explains his perception of world geography, where land comprises approximately two-fifth of the earth's surface, and the sea comprises the remaining three-fifths. He also divided the land into four continents:

- Asia, Europe, Africa

- the Americas

- Australia

- Oceania

He divided the oceans into the Pacific, Atlantic, Indian, northern Arctic, and the Antarctic.[1]

Another one of his books, Sin-gi Cheonheom, written initially as a medical text, explains the fifty-six kinds of natural elements. Hyegang also explains the attraction and repulsion between forces, utilization of gas, and the definitions and function of elements such as sulfuric acid, nitric acid, and hydrochloric acid in this book.[8]

- Writings by Hyegang

- 1834–1842: Nongjŏng hoeyo (Collective Summary of Agricultural Affairs)[2]

- 1834: Yukhaebŏp (Techniques of Hydraulics)[2]

- 1835: Ŭisang isu (Theories and Mathematics of Astronomy)[2]

- 1836: Ch'uch'ŭngnok or Chucheuk-ron (Documents on Inference)[2][8]

- 1842: Simgi tosŏl (Illustrations and Explanations of Important Machines)[2]

- 1850: Sŭpsan chinbŏl (Tools of Calculation Learning)[2]

- 1857: Kihak (기학; 氣學; transl. Study of Qi)[2][3][5]

- 1857: Chigu chŏnyo or Jigujeonyo (Canonical Outline of the Earth)[1][2][8]

- 1860: Unhwa ch'ŭkhŏm (Investigation of Dynamic Change)[2]

- 1866: Sin gi ch'ŏnhŏm or Sin-gi Cheonheom (Practical Experience of Physical Mechanism)[2][8]

- 1867: Sŏnggi unhwa (Dynamic Change of Stellar Qi or Evolution of Starry Material)[2][3][8]

In addition to restoring his works, Ajou University, a private research university in Suwon, Gyeonggi Province, South Korea, held a ceremony for the inauguration of Hyegang Hall, a new laboratory building, on May 8, 2022. The construction of the building was scheduled for completion in August 2022.[6][needs update]

- Yong-Taek Sohn (September 2010). "The Modernity of Nineteenth-Century Korean Confucianism: A Focus on Perceptions of World Geography in Choe Hangi's Jigujeonyo" (PDF). The Review of Korean Studies. 13 (3): 31–50. doi:10.25024/review.2010.13.3.002.

- Hoon, Jun Yong (2010). "A Korean Reading of Newtonian Mechanics in the Nineteenth Century". East Asian Science, Technology, and Medicine. 32 (32): 59–88. doi:10.1163/26669323-03201005. JSTOR 43150781 – via JSTOR.

- 전용훈 (March 2010). "A Comparison of Korean and Japanese Scholars' Attitudes toward Newtonian Science" (PDF). The Review of Korean Studies. 13 (1): 11–36. doi:10.25024/review.2010.13.1.001.

- "Hyegang's Sin-gi: Emphasis on Chucheuk". Korea Journal. 45 (2): 216–238. 2005. ISSN 0023-3900.

- Kim, Halla (October 18, 2022). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University – via Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- "Ground-breaking Ceremony for Hyegang Hall, a New Laboratory Building". 아주대학교 국제대학원. July 1, 2021.

- Pak, Sŏng-nae (October 18, 2005). Science and Technology in Korean History: Excursions, Innovations, and Issues. Jain Publishing Company. ISBN 9780895818386.

- "Korean Philosophy | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com.