2024_European_Parliament_election

2024 European Parliament election

Election for the 10th European Parliament

The 2024 European Parliament election is being held from 6 to 9 June.[1] This is the tenth parliamentary election since the first direct elections in 1979, and the first European Parliament election after Brexit.[2][3] This election will also coincide with a number of other elections in some European Union member states.

This article documents a current election. Information may change rapidly as the election progresses until official results have been published. Initial news reports may be unreliable, and the last updates to this article may not reflect the most current information. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

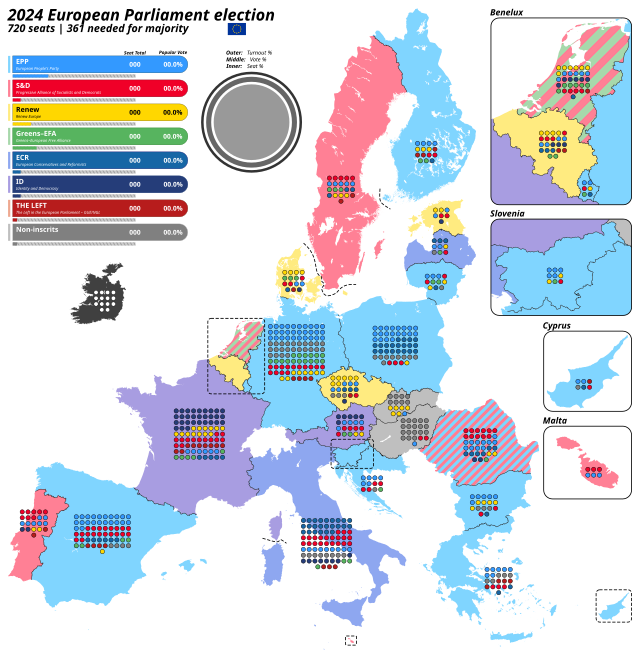

All 720 seats to the European Parliament 361 seats needed for a majority | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opinion polls | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Results by member state, shaded by EP group popular vote winner | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In the previous election held on 23–26 May 2019. In terms of the political Groups in the Parliament, they resulted in the EPP Group and S&D suffering significant losses, while the liberal/centrist (Renew), the Greens/EFA and ID made substantial gains, with ECR and The Left had small reduction. The European People's Party, led by Manfred Weber, won the most seats in the European Parliament, but was then unable to secure support from other parties for Weber as candidate for President of the Commission. After initial deadlock, the European Council decided to nominate Ursula von der Leyen as a compromise candidate to be the new Commission President, and the European Parliament elected von der Leyen with 383 votes (374 votes needed). The commission as a whole was then approved by the European Parliament on 27 November 2019, receiving 461 votes.

The 2019 election saw an increase in the turnout, when 50.7% of eligible voters had cast a vote compared with 42.5% of the 2014 election. This was the first time that turnout had increased since the first European Parliament election in 1979.[4]

In 2024, the Eurobarometer data shows that 71% of Europeans say they are likely to vote in June, 10% higher than those who said they would in 2019.[5]

Since the last European-wide election, the right has continued to rise across Europe, remaining however split, mainly by the Russian invasion of Ukraine and Russian relations issue.[6] In 2024, right-wing populist parties hold or share political power in Hungary (Fidesz), Italy (Brothers of Italy), Sweden (Sweden Democrats), Finland (Finns Party), Slovakia (Slovak National Party) and Croatia (Homeland Movement).[6] The centre-right EPP has "raised eyebrows" among some commentators for its efforts to charm parties in the ECR to create a broad conservative block,[7] which could upset the long-standing status-quo that has seen the EPP share power with the centre-left S&D and the centrist Renew Group.[8]

Elections to the European Parliament are regulated by the Treaty on European Union, Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, and the Act concerning the election of the members of the European Parliament by direct universal suffrage (the Electoral Act). The Electoral Act states that the electoral procedure is governed by the national provisions in each member state, subject to the provisions of the act.[9] Elections are conducted by direct universal suffrage by proportional representation using either a list system or single transferable vote.[10] The national electoral threshold may not exceed 5% of votes cast.[11]

Attempts at electoral reform

In June 2018, the Council agreed to change the EU electoral law and to reform old laws from the 1976 Electoral Act as amended in 2002.[12] New provisions included a mandatory 2% threshold for countries with more than 35 seats and rules to prevent voters from voting in multiple countries.[13] After the Act was adopted by the Council following consent given by the European Parliament in July 2018, not all member states ratified the Act prior to the 2019 elections, which took place under the old rules. As of 2023, the reform has yet to be ratified by Cyprus and Spain;[14] Germany only ratified in summer 2023.[15]

On 3 May 2022, the European Parliament voted to propose a new electoral law, which would contain provisions for electing 28 seats on transnational lists.[16] As of 2024, this reform has not been approved by the Council, which must approve it unanimously,[17] meaning the election will be conducted under the 1976 Electoral Act as amended in 2002.

Apportionment

As a result of Brexit, 27 seats from the British delegation were distributed to other countries in January 2020 (those elected in 2019, but not yet seated took their seats).[18] The other 46 seats were abolished with the total number of MEPs decreasing from 751 to 705.[19]

A report in the European Parliament proposed in February 2023 to modify the apportionment in the European Parliament and increase the number of MEPs from 705 to 716 in order to adapt to the development of the population and preserve degressive proportionality.[20][21] It was passed in the plenary in June 2023.[21] On 26 July 2023, the Council reached a preliminary agreement, which would increase the size of the European Parliament to 720 seats.[22] On 13 September 2023, the European Parliament consented to this decision,[23] which was adopted by the European Council on 22 September 2023.[24]

Electoral system by country

Spitzenkandidat system

In the run-up to the 2014 European Parliament elections a new informal system was unveiled for the selection of the European Commission President (known colloquially as the Spitzenkandidat system) dictating that whichever party group gained the most seats (or the one able to secure the support of a majority coalition) would see their candidate become President of the Commission.[60] In 2014, the candidate of the largest group, Jean-Claude Juncker, was eventually nominated and elected as Commission President.[61] European party leaders aimed to reintroduce the system in 2019, with them selecting lead candidates and organizing a televised debate between those candidates.[62] In the aftermath of the election German Defense Minister Ursula von der Leyen was chosen as Commission President, even though she had not been a candidate prior to the election, while Manfred Weber, lead candidate for the EPP, which had gained the most seats, was not nominated as he was unable to secure support from any other party.[63] Following this appointment of a Commission President who had not been a Spitzenkandidat, some called for the system to be abandonded, while others called for it to be revived in the 2024 elections.[64][65][66]

In 2023, multiple political parties at the European level announced their intentions to nominate a main candidate.[67][68][69][70] ECR[71][72] and ID have rejected doing so.[73]

Overview of party candidates for Commission President in 2024

European People's Party

The centre-right EPP held its congress in Bucharest on 6–7 March 2024 to elect its presidential candidate and adopt its election programme.[76] Nominees required the backing of their own member party and not more than two other EPP member parties from EU countries, with nominations closing on February 21.[77]

On 19 February 2024, Ursula von der Leyen announced her intention to run, supported by the CDU.[78] On 7 March von der Leyen was elected presidential candidate with 400 votes in favour, 89 against and 10 blank, out of the 737 EPP delegates at the EPP congress.[79] Among others, it is believed that the French and Slovenian delegations voted against.[80][81]

Party of European Socialists

The centre-left PES held its congress in Rome on 2 March. Nominees required the backing of nine PES full member parties or organisations, with nominations closing on 17 January.[82]

On 18 January, the PES announced that the Luxembourgish European Commissioner for Jobs and Social Rights Nicolas Schmit was the sole nominee to meet the nominating requirements.[83] He was then nominated on 2 March during the party congress, along with the adoption of the election programme.[84]

Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Party

The ALDE party held its extraordinary congress in Brussels on 20–21 March 2024.[85] On 7 March 2024, following months of speculation, Estonian Prime Minister Kaja Kallas announced that she had rejected the offer from ALDE to be the party's Spitzenkandidat.[86] Luxembourg’s former Prime Minister Xavier Bettel announced that he is not interested in the post either.[87]

On 11 March, the German FDP nominated Marie-Agnes Strack-Zimmermann to become presidential candidate.[88] She was then elected on March 20 during the party congress, along with the adoption of the election programme.[89][90]

European Democratic Party

During the 8 March 2024 Convention in Florence, the European Democratic Party nominated Sandro Gozi as its lead candidate and approved its election programme.[91]

European Green Party

During the 2–4 February 2024 congress in Lyon, the European Green Party elected Terry Reintke and Bas Eickhout as its two presidential candidates and adopted its election programme.[92][93][94] Nominees were Bas Eickhout, Elīna Pinto, Terry Reintke, Benedetta Scuderi.[95][96]

European Free Alliance

In October 2023, the congress of the European Free Alliance elected Maylis Roßberg and Raül Romeva as its presidential candidates, and adopted its election programme.[97][98]

Party of the European Left

During the 24–25 February 2024 congress in Ljubljana,[99] the PEL elected Walter Baier as its presidential candidate and adopted its election programme.[100]

European Christian Political Movement

In a meeting held on 24 February 2024, the European Christian Political Movement appointed party president Valeriu Ghilețchi as its lead candidate for the European Commission.[101]

European Pirate Party

At its General Assembly in Luxembourg in January 2024, the European Pirate Party nominated Marcel Kolaja and Anja Hirschel as lead candidates.[102]

Volt Europa

On 27 November 2023, Volt Europa adopted its European election programme at its General Assembly in Paris.[103] During the 6–7 April 2024 campaign launch event in Brussels the party elected German MEP Damian Boeselager and Dutch MEP Sophie in 't Veld as its lead candidates.[104] Regarding which European Parliament group to join after the elections, Boeselager said he was “open to discussions” between remaining in Greens/EFA or joining Renew Europe in due course.[105] To emphasise its demand for transnational lists, Volt Europa also presented a symbolic transnational list for the election alongside its leading candidates.[106]

Issues

Economy

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2024) |

Climate change

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2024) |

Foreign policy

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2024) |

Immigration

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2024) |

Potential enlargement

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2024) |

The future of Ursula von der Leyen

Ursula von der Leyen, the current European Commission President, did not formally announce her intention to stand for a second term until February 2024. This led to speculation about other potential EPP candidates, such as President of the European Parliament Roberta Metsola. However, on 19 February 2024, von der Leyen announced her intention to seek a second term.[78] and on 7 March she was elected European People's Party presidential candidate with 400 votes in favour, 89 against and 10 blank, out of the 737 EPP congressional delegates.[79]

In Germany, the coalition government had also agreed to support the spitzenkandidat system,[107] implicitly accepting the prospect of von der Leyen, who within Germany hails from the opposition CDU party, becoming Commission President again, depending on the election results. Otherwise, the German government coalition agreement grants the right to nominate the next German EU Commissioner to the Greens, provided the Commission President is not from Germany.[108]

The future of Charles Michel

In January 2024, Charles Michel announced he would step down early as president of the European Council to run for the European Parliament instead.[109] This would have meant that European Union leaders would potentially discuss his successor in the summer[110] as, if elected to the European Parliament, he would have had to step down because of prohibition of the dual mandate.[111] His mandate had been to set to expire in November 2024.[112] For this unanticipated decision Michel was criticised by EU officials and diplomats.[113] He was criticised by his political ally Sophie in 't Veld who questioned his "credibility".[114] This timing was further crticised for potential disruptions it could cause, as Article 2(4) of the European Council's Rules of Procedure provide that, if its President leaves office early, he "shall be replaced, where necessary until the election of his or her successor, by the member of the European Council representing the Member State holding the six-monthly Presidency of the Council".[115] This would have been the Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban, whose country would be scheduled to take over the rotating presidency of the European Council on 1 July.[116] On 26 January 2024, Michel withdrew his candidacy and thus delayed his departure.[117]

Future of Identity and Democracy

Ahead of the 2024 European Parliament election, National Rally spokespeople Jordan Bardella and Caroline Parmentier announced they would part ways with Alternative for Germany after the election and not include the AfD in the ID group due to controversial statements on Nazi Germany made by AfD lead candidate Maximilian Krah in an interview and allegations of Chinese espionage influence on the party.[118][119] Italy's Lega and the Czech SPD backed the position taken by the National Rally,[120][121] but Vlaams Belang declined to support expulsion of the AfD from the ID group or rule out further cooperation with the AfD, while criticising Krah's remarks.[122] The Danish People's Party conditioned future cooperation with the AfD on Krah's exclusion from the ID group.[123] The AfD was expelled from the group on 23 May.[124]

European Parliament groups

After the European elections, there are often changes or creation of new political groups by the national parties in the European Parliament.[125] This concerns both the new parties that have not yet announced which group they will be part of, and the parties already present in the European Parliament who choose to change group at the beginning of a new legislature.[125] According to the Parliament’s rules of procedure, a political group requires at least 23 MEPs from at least one-quarter of the Member States (7 out of 27), and a political declaration, setting out the purpose of the group.[126]

Several news outlets have speculated on the possibility of a new group guided by the German Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht party, created in January 2024.[127][128][129] This 'left-conservative' and eurosceptic group could include also M5S, SMER, and Hlas.[125]

After the expulsion of the AfD from ID, it is uncertain where its MEPs will be part of a group after the election. On 30 May, RTL Hungary reported that MHM and AfD were considering forming a new group.[130] This 'far-right' and eurosceptic group could include also Niki and Republic Movement.[125] After Revival was expelled from IDP, the party organized the 'Sofia Declaration' with the Republic Movement, Forum for Democracy, Our Homeland Movement, Alternative for Sweden and the Agricultural Livestock Party of Greece on 12 April 2024.[131] Czech Republic in First Place! stated they would either join ID or a "pacifist" and eurosceptic group with parties like the Republic Movement.[132]

Debates

| Date and time | Location | Organisers | Moderators | Language | Participants P Present A Absent I Invited NI Not invited | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPP | PES | ALDE | EDP | EGP | EFA | ID | ECR | PEL | ECPM | |||||

| 29 April 2024 19:00 CET[133][134] |

Theater aan het Vrijthof, Maastricht, Netherlands | Studio Europa Maastricht, Politico Europe |

Barbara Moens, Marcia Luyten | English | P von der Leyen |

P Schmit |

P Strack-Zimmermann[lower-alpha 16] |

P Eickhout |

P Roßberg |

P Vistisen[lower-alpha 2] |

A | P Baier |

P Ghilețchi | |

| 21 May 2024 16:00 CET[135] |

Brussels, Belgium | Bruegel, Financial Times |

Maria Demertzis, Henry Foy | English | P von der Leyen |

P Schmit |

P Gozi[lower-alpha 17] |

NI | NI | P Vistisen[lower-alpha 2] |

NI | NI | NI | |

| 23 May 2024 17:00 CET[136][137] |

Espace Léopold, Brussels, Belgium | European Broadcasting Union, European Parliament |

Annelies Beck, Martin Řezníček | English | P von der Leyen |

P Schmit |

P Gozi[lower-alpha 17] |

P Reintke |

NI | NI | NI | P Baier |

NI | |

29 April (Maastricht, Netherlands)

The first debate was held on Monday, 29 April 2024 from 19:00 to 20:30 CET at the Theater aan het Vrijthof in Maastricht, Netherlands.[134] It was hosted by Studio Europa Maastricht and Politico Europe and was EBU’s Eurovision News Exchange distributed the feed to its public service media network of members.[134] An initiative of Maastricht University, it was the third edition of the so-called "Maastrich Debate" [134][138] All ten registered European Political parties were invited to the debate.[134]

The debate questions focused on three main themes: climate change, foreign and security policy, and EU democracy.[134] During the debate, Ursula von der Leyen indicated she would be open to a deal with the European Conservatives and Reformists group after the election saying that the collaboration “depends very much on how the composition of the Parliament is, and who is in what group”.[139]

21 May (Brussels, Belgium)

The second debate was held on Tuesday, 21 May 2024 from 17:00 to 18:15 in Brussels, Belgium.[135] It was hosted by the think tank Bruegel and the Financial Times. The debate questions focused on economic policy in the EU.[140][141]

23 May (Brussels, Belgium)

The third debate will be held on Thursday, 23 May 2024 from 15:00 to 17:00 CET at the European Parliament in Brussels, Belgium.[142][143] It will be hosted by the European Broadcasting Union together with the European Parliament and it will be broadcast on public service media channels and online platforms members.[142] The debate will take place in English, with interpretation into all 24 official EU languages and International Sign Language. It will be the third edition of the so-called "Eurovision Debate".

Invitations to the debate were sent by the EBU to the ten recognised European Political parties, with only one lead candidate allowed to be nominated from each of the seven Political groups of the European Parliament.[142] On 7 May, EBU announced the candidates for the debate. Two parties, the ECR and ID, were considered by EBU not eligible to take part in the debate, since they have not nominated lead candidates for the Presidency of the European Commission and.[144][145]

The debate questions will focus on six main topics: Economy and Jobs, Defence and Security, Climate and Environment, Democracy and Leadership, Migration and Borders, Innovation and Technology.[146]

Several voting advice applications at the European level have been developed to help voters choose their candidates. Some of this applications could collect user data for research or commercial purpose.

- EUROMAT allows users to compare their positions on 20 statements with the answers given by the European political parties.[147] The result is presented as a percentage of agreement with each party. The EUROMAT was created as a joint project of the NGOs Pulse of Europe and Polis 180 and the blog Der (europäische) Föderalist and is available in eight languages.[148][149]

- Votematch.eu is a comprehensive collection of VAAs, with a unique application tailored for each member state.[150] Due to the variation in political parties across countries, Votematch.eu provides a specific application for each nation. This application first matches users with political parties within their own country. After this initial matching, users can compare their results with those in other member states. The overall platform was developed by German bpb and Dutch ProDemos.

- VoteTracker.eu website allows users to visualise the votes of MEPs of the 2019–2024 legislature on 18 selected votes, and to find the MEPs who best match their convictions.[151]

- EuroMPmatch is a collaborative project between EUmatrix and the European University Institute aimed at enhancing citizen engagement in EU policy-making. By analyzing MEPs' actual voting records on 20 key topics, the project offers citizens a quiz to determine alignment with MEPs, parties, and political groups.[152][153]

- EU&I, developed by the European University Institute in Florence, offers 30 questions to which the user can answer from ‘completely agree’ to ‘completely disagree’.[154] They can then give more weight to certain questions. The result is presented as a percentage of agreement with each national party. The site has been translated into 20 languages.[155]

- Adeno is an application that allows users to discover the European group that best matches their convictions through 100 questions (20 in the express mode) covering 10 themes. The application also offers a multiplayer mode. It is available on Android[156] and iPhone.[157]

- Palumba is an application, developed by an association of young professionals, offers 27 questions to be answered ‘for’, ‘against’ or ‘neutral’.[158] Explanations are provided for each question. The application provides the result in the form of a percentage of agreement for each European group and displays the closest national parties. The application is available on Android and iPhone and is available in over 30 languages (including regional dialects)[159]

Polling aggregations

Seat projections

Europe Elects, Der Föderalist and Politico Europe have been presenting seat projections throughout the legislative period. Other institutes started presenting data during the election campaign. All projections make their national-level data transparent, except Politico Europe, which only presents aggregate EU-level data.

| Polling aggregator | Date updated | Number of seats | The Left | S&D | G/EFA | Renew | EPP | ECR | ID | NI | Others | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Politico Europe[160] | 6 June 2024 | 720 | 32 | 143 | 41 | 75 | 173 | 76 | 67 | 58 | 55 | |

| election.de[161] | 6 June 2024 | 720 | 42 | 138 | 58 | 85 | 181 | 82 | 69 | 65 | – | |

| Cassandra-odds.com[162] | 5 June 2024 | 720 | 38 | 145 | 57 | 89 | 167 | 84 | 73 | 67 | – | |

| BiDiMedia[163] | 4 June 2024 | 720 | 44 | 140 | 46 | 86 | 177 | 79 | 74 | 74 | – | |

| Europe Elects[164] | 4 June 2024 | 720 | 38 | 136 | 55 | 81 | 182 | 79 | 69 | 76 | 4 | |

| Der Föderalist[165] | Baseline[lower-alpha 18] | 3 Jun 2024 | 720 | 37 | 136 | 57 | 81 | 172 | 79 | 66 | 50 | 42 |

| Dynamic[lower-alpha 19] | 720 | 40 | 137 | 58 | 85 | 186 | 80 | 78 | 56 | – | ||

| PolitPro[166] | 24 May 2024 | 720 | 38 | 142 | 43 | 86 | 167 | 70 | 91 | 46 | 33 | |

| Euronews[167] | 23 May 2024 | 720 | 43 | 135 | 54 | 82 | 181 | 80 | 83 | 62 | – | |

| corneliushirsch.com[168] | 9 May 2024 | 720 | 43 | 137 | 48 | 87 | 183 | 82 | 94 | 46 | – | |

| euobserver[169] | 5 June 2024 | 720 | 43 | 140 | 52 | 79 | 178 | 89 | 63 | 76 | - | |

| 2019 election | After Brexit | 1 Feb 2020 | 705 | 40 | 148 | 67 | 97 | 187 | 62 | 76 | 28 | – |

| Before Brexit | 26 May 2019 | 751 | 41 | 154 | 74 | 108 | 182 | 62 | 73 | 57 | – | |

Popular vote projections

Europe Elects has been presenting popular vote projections throughout the legislative period. Other institutes started presenting data during the election campaign.

| Polling aggregator | Date updated | The Left | S&D | G/EFA | Renew | EPP | ECR | ID | NI | Others | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Europe Elects[164] | 31 May 2024 | 6.4% | 19.8% | 7.7% | 11.2% | 21.1% | 12.2% | 8.5% | 8.9% | 4.2% | ||

| The Economist[170] | 31 May 2024 | 6.0% | 17.0% | 6.0% | 10.0% | 22.0% | 10.0% | 11.0% | 4.0% | 14.0% | ||

| PolitPro[171] | 24 May 2024 | 5.3% | 19.7% | 6.0% | 11.9% | 23.2% | 9.7% | 12.6% | 6.4% | 5.2% | ||

| 2019 election | ||||||||||||

| Before Brexit | 26 May 2019 | 6.5% | 18.5% | 11.7% | 13.0% | 21.0% | 8.2% | 10.8% | 7.2% | 3.1% | ||

About 357 million people are eligible to vote in 27 countries.[172][173]

Conflict with Portuguese national holiday

The dates chosen for the elections conflict with a long weekend in Portugal, where Portugal Day, a national holiday, is celebrated on 10 June, which is expected to suppress turnout.[174] Despite an attempt by Portuguese leaders to find a compromise, no change was made to the default date of 6–9 June,[175] which required unanimity to be changed.

Qatargate

The ongoing Qatargate corruption scandal, which began in December 2022, has destabilized the European Parliament following the arrest of several MEPs including Marc Tarabella; Andrea Cozzolino and Eva Kaili who was stripped of her vice presidency. Other suspects in the case include Francesco Giorgi, the parliamentary assistant of MEP Andrea Cozzolino, Pier Antonio Panzeri, founder of the Fight Impunity NGO; Niccolo Figa-Talamanca, head of the No Peace Without Justice NGO; and Luca Visentini, head of the International Trade Union Confederation.[176][177]

Following the scandal, the European Parliament revised its rules of procedure and its code of conduct in September 2023[178] placing six main obligations on MEPs:[179] [180]

- Detailed declaration of private interests, including those from the 3 years prior to their election

- When external income exceeds €5,000, all the entities from which their income is received must be listed

- All conflicts of interest must be resolved or declared

- Not engaging in paid lobbying activities linked directly to the EU’s decision-making process

- Meetings with interested parties can only be with people who sign up to the EU's Transparency Register[181] and MEPs must make a disclosure of such meetings and also of meetings held with representatives of third country diplomats

- Make a declaration of all assets and liabilities at the beginning, and again at the end, of every term of office

Hungary

The European Parliament views Hungary as a "hybrid regime of electoral autocracy" since 2022 and considers Hungary according to Article 7.1 of the Treaty on European Union in clear risk of a serious breach of the Treaty on European Union.[182][183] In January 2024, a majority of European Parliament MEPs voted for a resolution demanding that the EU Council considers that Hungary be stripped of its EU voting rights under Article 7 of the Treaty.[184]

Russian influence scandal

On 27 March, the Czech Republic sanctioned the news site Voice of Europe, claiming that the site is part of a network for pro-Russian influence.[185] The following day, Belgian Prime Minister De Croo, referring to the sanctions during a debate in the Belgian parliament, said that Russia had targeted MEPs, but also paid them.[186] On 2 April, the Czech news portal Denik N reported, citing several ministers, that there are audio recordings of the German far-right politician Petr Bystron (MP, AfD) that incriminate him of having accepted money.[187] On 12 April, it became known that the Belgian public prosecutor's office is investigating whether European politicians were paid to spread Russian propaganda. In addition to Bystron, the investigation is also targeting Dutch MEP Marcel de Graaff (FvD) and German MEP Maximilian Krah (AfD). Ukrainian politician and businessman Viktor Medvedchuk, who is close to Russian President Vladimir Putin, is believed to be the man behind Voice of Europe.[188]

- List of MEPs who stood down at the 2024 European Parliament election

- 2024 elections in the European Union

Concurrent elections

Belgium: general elections (parliamentary and regional elections)

Belgium: general elections (parliamentary and regional elections) Bulgaria: parliamentary elections

Bulgaria: parliamentary elections Germany: local/regional elections, 2024 Hamburg borough elections

Germany: local/regional elections, 2024 Hamburg borough elections Hungary: local elections

Hungary: local elections Ireland: local elections

Ireland: local elections Italy: local elections, 2024 Piedmontese regional election

Italy: local elections, 2024 Piedmontese regional election Malta: local elections

Malta: local elections Romania: local elections

Romania: local elections

- Strack-Zimmermann is the candidate representing ALDE. In addition Sandro Gozi is the candidate representing the EDP, and Valérie Hayer is the candidate representing L'Europe Ensemble

- Anders Vistisen was selected to participate on behalf of the party in pre-election debates, but he is not a lead candidate.[74][75]

- This is the maximum vote share necessary to mathematically guarantee winning a seat. It is here calculated as the Droop quota for each country. Where the legal threshold exceeds this threshold, the legal threshold is shown instead.

- Depends on the constituency: 50% in the German-speaking electoral college, ~11.1% in the French-speaking electoral college, and ~7.1% in the Dutch-speaking electoral college.

- Seats are apportioned to parties nationally. A party can choose to only stand in some of the 16 states and have its national seat count be subapportioned to those states. Only the CDU and the CSU have done this in previous elections.

- Depends on the constituency: 20% in Dublin, ~16.7% in Midlands–North-West and South. As Single transferable vote is a party-blind voting system, this threshold applies for an individual candidate, not for the party as a whole.

- As Single transferable vote is a party-blind voting system, this threshold applies for an individual candidate, not for the party as a whole.

- Lead candidate for ALDE, representing in the debate the entire Renew Europe parliamentary group

- Lead candidate for EDP, representing in the debate the entire Renew Europe parliamentary group

- Groups all parties not represented in the European Parliament into "others", unless it is a member of a political party at the European level.

- "Council confirms 6 to 9 June 2024 as dates for next European Parliament elections". www.consilium.europa.eu. 22 May 2023. Retrieved 24 May 2023.

- "EUR-Lex - 12007L/TXT - EN - EUR-Lex". eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- "Elections". European Parliament. Archived from the original on 28 June 2018. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- Coi, Giovanna (22 March 2024). "Vote for me! Why turnout is the EU Parliament's biggest election challenge". Politico Europe.

- Mackenzie, Lucia; Coi, Giovanna (17 April 2024). "How to win the European election". Politico Europe.

- "Europe's largest political party veers right ahead of 2024 election | Financial Times". Financial Times. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- Rosa, Brunello; Poettering, Benediict. "Can a Centre-Right Coalition Emerge After The Next EU Elections?". London School of Economics and Political Science. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- "Act concerning the election of the members of the European Parliament by direct universal suffrage". EUR-Lex. 23 September 2002. Article 8.

- "Act concerning the election of the members of the European Parliament by direct universal suffrage". EUR-Lex. 23 September 2002. Article 1.

- "Act concerning the election of the members of the European Parliament by direct universal suffrage". EUR-Lex. 23 September 2002. Article 3.

- "EUR-Lex - 32018D0994 - EN - EUR-Lex". eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- "Two years to go: What to expect from the 2024 European Parliament elections". Jacques Delors Centre. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- "European Parliament votes in favor of reforming EU elections". POLITICO. 3 May 2022. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- "LEAK: Most countries hesitant about EU electoral law reform". www.euractiv.com. 5 July 2023. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- "Italian proposal for who gets British MEP seats". POLITICO. 26 April 2017. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- "MEPs propose cut in their ranks after Brexit". POLITICO. 7 September 2017. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- "Draft report on the composition of the European Parliament (2021/2229(INL) – 2023/0900(NLE))" (PDF). European Parliament. 14 February 2023. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- "European elections 2024: Parliament proposes more seats for nine EU countries | News | European Parliament". www.europarl.europa.eu. 15 June 2023. Retrieved 15 June 2023.

- "European Parliament set to grow by 15 MEPs in 2024". POLITICO. 28 July 2023. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- "2024 European elections: 15 additional seats divided between 12 countries | News | European Parliament". www.europarl.europa.eu. 13 September 2023. Retrieved 14 September 2023.

- "EUR-Lex - 32023D2061 - EN - EUR-Lex". eur-lex.europa.eu. Retrieved 28 September 2023.

- "Minimum age to stand as a candidate in European elections" (PDF). www.europarl.europa.eu. June 2023. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- Oelbermann, Kai Friederike; Pukelsheim, Friedrich (July 2020). "The European Elections of May 2019" (PDF). europarl.europa.eu. p. 14.

- "Austria - How to vote". European elections 2024: all you need to know. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- "Belgium - How to vote". European elections 2024: all you need to know. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- "16-year-olds in Belgium will be able to vote in European elections from 2024". www.brusselstimes.com. Retrieved 7 January 2023.

- Arnoudt, Rik (21 March 2024). "Jongeren van 16 of 17 jaar zullen dan toch moeten gaan stemmen voor Europese verkiezingen". www.vrt.be (in Dutch). Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- "Bulgaria - How to vote". European elections 2024: all you need to know. Retrieved 10 April 2024.

- ИЗБОРЕН КОДЕКС [ELECTORAL CODE] (Annex № 3, Article II & III). 2016. p. 225. Retrieved 5 December 2023 – via Venice Commission.

- "Croatia - How to vote". European elections 2024: all you need to know. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- "Cyprus - How to vote". European elections 2024: all you need to know. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- Ο Περί της Εκλογής των Μελών του Ευρωπαϊκού Κοινοβουλίου Νόμος του 2004 (10(I)/2004) [The 2004 Law on the Election of Members of the European Parliament (10(I)/2004)] (10 (I), 23) (in Cypriot Greek). 2004 – via Cyprus Bar Association.

- "Volby do Evropského parlamentu - základní informace pro voliče - Volby". www.mvcr.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 28 September 2023.

- Af /ritzau (5 October 2023). "EU-valg: Her er datoen". ekstrabladet.dk (in Danish). Retrieved 5 October 2023.

- "| Valimised Eestis". www.valimised.ee. Retrieved 6 October 2023.

- Oy, Edita Publishing. "FINLEX ® - Uppdaterad lagstiftning: Vallag 714/1998". www.finlex.fi (in Swedish). 160 §. Retrieved 30 July 2023.

- "Quelles sont les dates des prochaines élections ?". Service-Public.fr (in French). 12 October 2023.

- "Wahltermin Europawahl 2024 - Die Bundeswahlleiterin". www.bundeswahlleiterin.de. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- "Greece - How to vote". European elections 2024: all you need to know. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- "Eldőlt, mikor lesz 2024-ben az EP- és a magyar önkormányzati választás". www.hvg.hu. 17 May 2023. Retrieved 17 May 2023.

- "It's official! The Local and European Elections will be held on Friday 7 June". www.thejournal.ie. 14 March 2024. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- "Per le elezioni europee si voterà in un giorno e mezzo, l'8 e 9 giugno". Il Post (in Italian). 25 January 2024. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- "Grozījumi Eiropas Parlamenta vēlēšanu likumā" [Amendments to the European Union Elections Act]. LIKUMI.LV (in Latvian). Retrieved 20 July 2023.

- Eiropas Parlamenta vēlēšanu likums [Election to the European Parliament Law] (44 (1)). 2019.

- "Luxembourg - How to vote". European elections 2024: all you need to know. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- "Malta - How to vote". European elections 2024: all you need to know. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- "Dag van stemming". Kiesraad.nl (in Dutch). 20 May 2016. Retrieved 29 July 2023.

- "Poland - How to vote". European elections 2024: all you need to know. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- "How to vote in Portugal". European elections.

- "Romania - How to vote". European elections 2024: all you need to know. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- "Slovakia - How to vote". European elections 2024: all you need to know. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- "Slovenia - How to vote". European elections 2024: all you need to know. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- "Volitve poslancev iz Slovenije v Evropski parlament: Pregled strank in kandidatov". Evropskevolitve2024.news (in Sinhala). 21 May 2024. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- "Vallag (2005:837)". www.riksdagen.se (in Swedish). 1 kap., 2 & 3 §. Retrieved 30 July 2023.

- "What is a spitzenkandidat?". euronews. 24 April 2019. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- "The EU's Spitzenkandidat 2.0 is heading for a fall | Financial Times". www.ft.com. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- "First clashes liven up last EU Spitzenkandidat debate ahead of election". www.euractiv.com. 16 May 2019. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- "Who killed the Spitzenkandidat?". POLITICO. 5 July 2019. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- "Future of spitzenkandidaten could rest on next year's EU elections". euronews. 19 May 2023. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- "Is the Spitzenkandidat system really dead? Not if we act now". www.euractiv.com. 13 November 2019. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- "Why the EU's Spitzenkandidaten procedure should be revived before the next European Parliament elections". EUROPP. 29 July 2021. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- "EPP backs spitzenkandidat, as other right parties abandon the process". www.euractiv.com. 5 May 2023. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- "Nicolas who? Socialists close in on challenger to take on Ursula von der Leyen". www.politico.eu. 16 January 2024. Retrieved 16 January 2024.

- "European Greens to field Spitzenkandidaten duo in 2024 EU elections". European Greens. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- "The Left will have a spitzenkandidat for 2024 EU elections". www.euractiv.com. 19 June 2023. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- "ECR adopts manifesto but snubs lead candidate pick amid rifts". Euractiv. 25 April 2024.

- "ECR Party adopts manifesto for European elections, decides not to put forward a lead candidate". ECR Party. 24 April 2024.

- "Liberals divided over 2024 EU election campaign strategy". POLITICO. 5 July 2023. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- "Far-right picks Danish MEP as token 'lead candidate'". EUobserver. 7 March 2024. Retrieved 1 April 2024.

- "Keeping it on the VDL: Ursula the reluctant campaigner". Politico Europe. 8 March 2024.

- "European People's Party Congress in Bucharest". www.epp.eu. 11 January 2024.

- "EPP 2024 Congress Voting Regulation" (PDF). www.epp2024.eu. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 February 2024.

- Camut, Nicolas; von der Burchard, Hans (19 February 2024). "Ursula von der Leyen announces bid for 2nd term". POLITICO. Retrieved 26 February 2024.

- "Europe's conservatives back Ursula von der Leyen for second term as Commission president". Politico EU. 7 March 2024.

- "EPP eyes socialists, liberals for pro-EU coalition as Breton questions von der Leyen". Euractiv. 8 March 2024.

- "Michel Barnier refuses to back Ursula von der Leyen for second term as EU Commission chief". Politico EU. 7 March 2024.

- "PES Election Congress to take place in Rome". www.pes.eu. 12 January 2024. Retrieved 16 January 2024.

- "Socialists pick Nicolas Schmit to lead EU election campaign". POLITICO. 18 January 2024. Retrieved 18 January 2024.

- "ALDE Party Council: two new Italian members, lead candidate process, new Secretary General". aldeparty.eu. 21 October 2023.

- ERR (7 March 2024). "Kallas: ma ei hakka ALDE esikandidaadiks Euroopa Parlamendi valimistel". ERR (in Estonian). Retrieved 8 March 2024.

- "Estonia's Kallas, Luxembourg's Bettel rule out EU liberals lead candidate job". Euractiv. 8 March 2024.

- "Strack-Zimmermann nominated as ALDE Party lead candidate". aldeparty.eu. 11 March 2024.

- "Liberals confirm lead candidate, adopt 2024 Manifesto in Brussels". aldeparty.eu. 20 March 2024.

- "Low appetite for EU liberals' election campaign kick-off". Euractiv. 21 March 2024.

- "The convention of the European Democratic Party - Website of the European Democrats". democrats.eu. 15 February 2024. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- "European Greens field Terry Reintke and Bas Eickhout as top candidates ('Spitzenkandidaten') for EU elections". European Greens. 3 February 2024.

- "Greens pledge to cater to farmers, call for greater climate ambition". Euractiv. 5 February 2024.

- Niranjan, Ajit (5 February 2024). "EU Greens pick veteran MEPs to lead election campaign". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- "Four Greens enter the race to become European Green Party leading candidates". European Greens. 30 November 2023.

- "Two MEPs, two outsiders join race for Greens' EU election lead candidates". Euractiv. 30 November 2023.

- Griera, Max (17 October 2023). "Party pushing 'self-determination' in EU election stint fields two top candidates". Euractiv.

- "Maylis Roßberg and Raül Romeva ratified as EFA Spitzenkandidaten tandem". E-f-a.org. 23 October 2023.

- "European Left General Aassembly In Ljubljana". www.european-left.org.

- "The Party of the European Left elects Walter Baier as Spitzenkandidat". European Left. 25 February 2024.

- "President Valeriu Ghilețchi is appointed ECPM's lead candidate for the European Commission". European Christian Political Movement. 24 February 2024.

- "Anja Hirschel ist Spitzenkandidatin der Piratenpartei • Table.Media". Table.Media (in German). 31 January 2024. Retrieved 4 February 2024.

- "Volt Europa Unveils Bold Vision for Europe and Elects New Leadership". Volt Europa. Retrieved 8 January 2024.

- "Volt elects European lead candidates and transnational list". Volt Europa. 7 April 2024.

- "Volt party determined to burst onto European political scene". Agence Europe. 9 April 2024.

- "Volt party elects Sophie IN 'T Veld and the German Damian Boeselager". euronews. 6 April 2024. Retrieved 10 April 2024.

- "Germany's conservatives back EU's von der Leyen for second term — if she wants it". POLITICO. 17 April 2023. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- "Koalitionsvertrag 2021-2025" (PDF). WiWo (in German).

- Henley, Jon; correspondent, Jon Henley Europe (7 January 2024). "Michel sparks scramble to stop Orbán taking control of European Council". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 7 January 2024.

- "EU's Charles Michel to quit Council presidency, run as MEP – DW – 01/07/2024". dw.com. Retrieved 7 January 2024.

- Henley, Jon (7 January 2024). "Michel sparks scramble to stop Orbán taking control of European Council". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 24 January 2024.

- "EU Council President Charles Michel to step down early". BBC News. 7 January 2024. Retrieved 8 January 2024.

- "'Pissed off, and rightly so.' EU fury at Charles Michel stepping down". POLITICO. 12 January 2024. Retrieved 24 January 2024.

- "The bad example set by European Council President Charles Michel". Le Monde.fr. 19 January 2024. Retrieved 24 January 2024.

- O'Carroll, Lisa (26 January 2024). "EU president to stay in post amid fears of Viktor Orbán getting role". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 26 January 2024.

- "France's National Rally won't sit with Alternative for Germany in EU Parliament". Politico. 21 May 2024.

- "French Far Right Splits With Germany's AfD In EU Parliament". Politico. 21 May 2024.

- "Far-right ID group expels Alternative for Germany". POLITICO. 23 May 2024. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- "At the bazaar of the political groups: Which parties could look for new partners in the European Parliament after the EU election?". Der (europäische) Föderalist. 28 May 2024.

- "Rules of Procedure of the European Parliament". European Parliament. 15 January 2021.

- "Germany's rebel Wagenknecht plots new left-wing group in EU Parliament". Euractiv. 22 February 2024.

- "A European Wagenknecht Group?". Europe Elects. 23 April 2024.

- "BSW seeks its own group in the EU Parliament". Table Europe. 24 April 2024.

- "A Mi Hazánk a német szélsőjobboldali Afd-vel alapítana új EP-frakciót". RTL Hungary. 30 January 2024.

- Volby do Evropského parlamentu 2024. Czech Television (in cz). 25 May 2024. Event occurs at 6:00. Retrieved 31 May 2024.

{{cite AV media}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - "The Maastricht Debate 2024". Maastricht Debate.

- "Economic choices for Europe: EU leadership debate 2024". Bruegel. Retrieved 22 May 2024.

- "Lead candidates debate - European Elections 2024". European Parliament.

- "Eurovision Debate 2024". EBU. 2 May 2024.

- "POLITICO partners with Studio Europa Maastricht to host 2024 Maastricht Debate". Politico Europe. 24 January 2024.

- "Von der Leyen opens the door to Europe's hard right". Politico Europe. 30 April 2024.

- "Renew, ID lead pre-EU election debate as EPP's von der Leyen keeps low profile". Euractiv. 22 May 2024.

- "The homegrown problems facing the EU's next leader". Financial Times. 22 May 2024.

- "2024 European elections: Media arrangements for Eurovision Debate and Election Night". European Parliament. 29 April 2024.

- "Eurovision Debate 2024 line-up announced". EBU. 7 May 2024.

- "Far right cries censorship after exclusion from EU election debate". Politico Europe. 13 May 2024.

- "Eurovision Debate: Further details announced". EBU. 16 May 2024.

- "EUROMAT for the 2024 European elections". EUROMAT. Retrieved 7 June 2024.

- "Election aid: Euromat soon online". TABLE EUROPE. 23 May 2024.

- "The EUROMAT for the 2024 European election". Der (europäische) Föderalist. 23 May 2024.

- "What party in the EU is your best match?". votematcheurope. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- "VoteTracker.eu". votetracker.eu. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

- "Euandi2024". Euandi2024. Retrieved 4 June 2024.

- "New EU&I platform launched to help voters navigate European Parliament Elections | UCD Research". www.ucd.ie. Retrieved 4 June 2024.

- "Adeno - Apps on Google Play". play.google.com. Retrieved 23 March 2024.

- "Palumba - If this cute pigeon can't help you vote in June, nothing will". www.palumba.eu. Retrieved 4 June 2024.

- "If this cute pigeon can't help you vote in June, nothing will! | European Youth Portal". youth.europa.eu. Retrieved 4 June 2024.

- "POLITICO Poll of Polls — European Election polls, trends and election news". POLITICO. 20 December 2023. Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- Moehl, Matthias (6 June 2024). "Wahl zum Europäischen Parlament - Prognose Stand 06.06.2024". election.de (in German). Retrieved 6 June 2024.

- Di Lella, Gianmarco (19 May 2024). "Chi vincerà le elezioni europee". Cassandra-odds.com (in Italian). Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- "EU Parliamentary Projection: Chaos on the Right". Europe Elects. 31 May 2024.

- Müller, Eingestellt von Manuel. "European Parliament seat projection (May 2024): The last polling numbers – who will win, who will lose, and who will form a majority?". Retrieved 3 June 2024.

- "EU-Parliament: Polls and trends for the European Parliament election 2024". politpro. 24 May 2024. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- "EPP leads European polls while far right makes dramatic gains". euronews. 23 May 2024. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- "2024 European Parliament Election Seat Projection". corneliushirsch.com. 5 May 2024. Retrieved 12 May 2024.

- "Pollwatch: Final EUobserver update before Sunday's big results night". EUobserver. 6 June 2024. Retrieved 7 June 2024.

- "European Parliament elections tracker: who's leading the polls?". The Economist. 2 May 2024. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- "EU-Parliament: Polls and trends for the European Parliament election 2024". politpro. 24 May 2024. Retrieved 24 May 2024.

- "European Parliament Election 2024". Europe elects. Retrieved 7 June 2024.

- "European elections 2024: people eligible to vote". Eurostat. 4 June 2024. Retrieved 7 June 2024.

- "EU riles Portugal by teeing up June dates for 2024 elections". POLITICO. 10 May 2023. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- "Council confirms 6 to 9 June 2024 as dates for next European Parliament elections". Council of the EU. Council of the EU Press Office. 22 May 2023.

- "Corruption, cash and confessions: Who are the key suspects in the Qatargate scandal ?". France 24. 21 January 2023. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- Clapp, Alexander (15 March 2023). "Opinion | It's a Spectacular Scandal, and a Warning to Europe". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 August 2023.

- How the European Parliament reacted to the biggest corruption scandal in its history https://www.newstatesman.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2024/02/21/TheReportCIPRsupplement9Feb2024.pdf

- How the European Parliament reacted to the biggest corruption scandal in its history https://www.newstatesman.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2024/02/21/TheReportCIPRsupplement9Feb2024.pdf

- "Home - European Union". 10 April 2024.

- Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs (25 July 2022). INTERIM REPORT on the proposal for a Council decision determining, pursuant to Article 7(1) of the Treaty on European Union, the existence of a clear risk of a serious breach by Hungary of the values on which the Union is founded (Report). European Parliament.

- "The Hungarian government threatens EU values, institutions, and funds, MEPs say | News | European Parliament". www.europarl.europa.eu. 18 January 2024.

- Wax, Eddy (18 January 2024). "EU Parliament calls to strip Hungary of voting rights in rule-of-law clash". POLITICO.

- "Russian influence scandal rocks EU". POLITICO. 29 March 2024. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- "Russian propaganda network paid MEPs, Belgian PM says". POLITICO. 28 March 2024. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- Prchal, Lukáš (2 April 2024). ""Důkazem mají být zvukové nahrávky." Co řekl Koudelka vládě o proruské síti a německém politiku Bystroňovi". Deník N (in Czech). Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- "Nieuw schandaal rond Russische beïnvloeding door 'Voice of Europe' treft Europees Parlement: deze namen worden genoemd". vrtnws.be (in Dutch). 12 April 2024. Retrieved 14 April 2024.

- Manuel Müller, Two years to go: What to expect from the 2024 European Parliament elections, Jacques Delors Centre, 30 May 2022.