Südschleife

Nürburgring

Race track in Nürburg, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany

The Nürburgring is a 150,000 person capacity motorsports complex located in the town of Nürburg, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. It features a Grand Prix race track built in 1984, and a long Nordschleife "North loop" track, built in the 1920s, around the village and medieval castle of Nürburg in the Eifel mountains. The north loop is 20.830 km (12.943 mi) long and contains more than 300 metres (1,000 feet) of elevation change from its lowest to highest points. Jackie Stewart nicknamed the track "The Green Hell".[2]

This article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (November 2019) |

| |

Configuration for GP-Strecke (2002–present)  Configuration for 24 Hours Circuit – Combined GP Circuit without Mercedes-Arena (2002–present) | |

| Location | Nürburg, Germany |

|---|---|

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) CEST (DST) |

| Coordinates | 50°20′08″N 6°56′51″E |

| Capacity | 150,000 |

| FIA Grade |

|

| Major events | Current:

Former:

|

| Website | https://nuerburgring.de |

| GP-Strecke (2001–present) | |

| Surface | Asphalt |

| Length | 5.1480 km (3.199 miles) |

| Turns | 15 |

| Race lap record | 1:28.139 ( |

| Sprint Circuit (2002–present) | |

| Surface | Asphalt |

| Length | 3.629 km (2.255 miles) |

| Turns | 12[1] |

| Race lap record | 1:19.322 ( |

| Oldtimer Circuit (2002–present) | |

| Surface | Asphalt |

| Length | 4.569 km (2.839 miles) |

| Turns | 12 |

| Race lap record | 1:36.325 ( |

| 24 Hours Circuit – Combined GP Circuit without Mercedes-Arena (2002–present) | |

| Surface | Asphalt/concrete |

| Length | 25.378 km (15.770 miles) |

| Turns | 170 |

| Race lap record | 8:08.006 ( |

| Nordschleife (1983–present) | |

| Surface | Asphalt/concrete |

| Length | 20.832 km (12.944 miles) |

| Turns | 154 |

| Race lap record | 6:25.91 ( |

| GP-Strecke with F1 Chicane (1995–2001) | |

| Surface | Asphalt |

| Length | 4.556 km (2.831 miles) |

| Turns | 12 |

| Race lap record | 1:18.354 ( |

| GP-Strecke without F1 Chicane (1984–2001) | |

| Surface | Asphalt |

| Length | 4.542 km (2.822 miles) |

| Turns | 12 |

| Race lap record | 1:21.533 ( |

| Nordschleife (1971–1982) | |

| Surface | Asphalt/concrete |

| Length | 22.835 km (14.189 miles) |

| Turns | 160 |

| Race lap record | 7:06.4 ( |

| Nordschleife (1967–1970) | |

| Surface | Asphalt/concrete |

| Length | 22.835 km (14.189 miles) |

| Turns | 160 |

| Race lap record | 7:40.800 ( |

| Nordschleife (1927–1966) | |

| Surface | Asphalt |

| Length | 22.800 km (14.167 miles) |

| Turns | 160 |

| Race lap record | 8:24.1 ( |

| Südschleife (1927–1982) | |

| Surface | Asphalt |

| Length | 7.747 km (4.814 miles) |

| Turns | 27 |

| Race lap record | 2:38.6 ( |

| Gesamtstrecke (1927–1982) | |

| Surface | Asphalt |

| Length | 28.265 km (17.563 miles) |

| Turns | 187 |

| Race lap record | 15:06.1 ( |

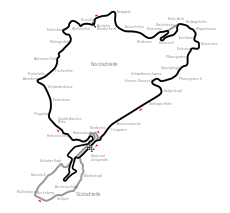

Originally, the track featured four configurations: the 28.265 km (17.563 mi)-long Gesamtstrecke ("Whole Course"), which in turn consisted of the 22.835 km (14.189 mi) Nordschleife ("North Loop") and the 7.747 km (4.814 mi) Südschleife ("South Loop"). There was also a 2.281 km (1.417 mi) warm-up loop called Zielschleife ("Finish Loop") or Betonschleife ("Concrete Loop"), around the pit area.[3]

Between 1982 and 1983, the start/finish area was demolished to create a new GP-Strecke, which is now used for all major and international racing events. However, the shortened Nordschleife is still in use for racing, testing and public access.

1925–1939: The beginning of the "Nürburg-Ring"

In 1907, the first Eifelrennen race was held on the one-off Taunus circuit, a 117 km (73 mi)circuit made up of public roads starting between the towns of Wehrheim and Saalburg just north of Frankfurt. In the early 1920s, ADAC Eifelrennen races were held on the twisty 33.2 km (20.6 mi) Nideggen public road circuit near Cologne and Bonn. Around 1925, the construction of a dedicated race track was proposed just south of the Nideggen circuit around the ancient castle of the town of Nürburg, following the examples of Italy's Monza and Targa Florio courses, and Berlin's AVUS, yet with a different character. The layout of the circuit in the mountains was similar to the Targa Florio event, one of the most important motor races at that time. The original Nürburgring was to be a showcase for German automotive engineering and racing talent. Construction of the track, designed by the Eichler Architekturbüro from Ravensburg (led by architect Gustav Eichler), began in September 1925.

The track was completed in spring 1927, and the ADAC Eifelrennen races were continued there. The first races to take place on 18 June 1927 showed motorcycles and sidecars, and were won by Toni Ulmen on an English 350 cc Velocette. The cars followed a day later, and Rudolf Caracciola was the winner of the over 5000 cc class in a supercharged Mercedes-Benz "K". In addition, the track was opened to the public in the evenings and on weekends, as a one-way toll road.[4] The entire track consisted of 174 bends (prior to 1971 changes), and averaged 8 to 9 metres (8.7 to 9.8 yd) in width. The fastest time ever around the full Gesamtstrecke was by Louis Chiron, at an average speed of 112.31 km/h (69.79 mph) in his Bugatti.

In 1929 the full Nürburgring was used for the last time in major racing events, as future Grands Prix would be held only on the Nordschleife. Motorcycles and minor races primarily used the shorter and safer Südschleife. Memorable pre-war races at the circuit featured the talents of early Ringmeister (Ringmasters) such as Rudolf Caracciola, Tazio Nuvolari, and Bernd Rosemeyer.

1947–1970: "The Green Hell"

After World War II, racing resumed in 1947, and in 1951, the Nordschleife of the Nürburgring again became the main venue for the German Grand Prix as part of the Formula One World Championship (with the exception of 1959, when it was held on the AVUS in Berlin). A new group of Ringmeister arose to dominate the race – Alberto Ascari, Juan Manuel Fangio, Stirling Moss, Jim Clark, John Surtees, Jackie Stewart and Jacky Ickx.

On 5 August 1961, during practice for the 1961 German Grand Prix, Phil Hill became the first person to complete a lap of the Nordschleife in under 9 minutes, with a lap of 8 minutes 55.2 seconds (153.4 km/h or 95.3 mph) in the Ferrari 156 "Sharknose" Formula One car. Over half a century later, even the highest performing road cars still have difficulty breaking 8 minutes without a professional race driver or one very familiar with the track. Also, several rounds of the German motorcycle Grand Prix were held, mostly on the 7.7 km (4.8 mi) Südschleife, but the Hockenheimring and the Solitudering were the main sites for Grand Prix motorcycle racing.

In 1953, the ADAC 1000 km Nürburgring race was introduced, an Endurance race and Sports car racing event that counted towards the World Sportscar Championship for decades. The 24 Hours Nürburgring for touring car racing was added in 1970.

By the late 1960s, the Nordschleife and many other tracks were becoming increasingly dangerous for the latest generation of F1 cars. In 1967, a chicane was added before the start/finish straight, called Hohenrain, in order to reduce speeds at the pit lane entry. This made the track 25 m (27 yd) longer. Even this change, however, was not enough to keep Stewart from nicknaming it "The Green Hell" (German: Die Grüne Hölle) following his victory in the 1968 German Grand Prix amid a driving rainstorm and thick fog. In 1970, after the fatal crash of Piers Courage at Zandvoort, the F1 drivers decided at the French Grand Prix to boycott the Nürburgring unless major changes were made, as they had done at Spa the year before. The changes were not possible on short notice, and the German GP was moved to the Hockenheimring, which had already been modified.

1971–1983: Changes

In accordance with the demands of the F1 drivers, the Nordschleife was reconstructed by taking out some bumps, smoothing out some sudden jumps (particularly at Brünnchen), and installing Armco safety barriers. The track was made straighter, following the race line, which reduced the number of corners. The German GP could be hosted at the Nürburgring again, and was for another six years from 1971 to 1976.

In 1973 the entrance into the dangerous and bumpy Kallenhard corner was made slower by adding another left-hand corner after the fast Metzgesfeld sweeping corner. Safety was improved again later on by removing the jumps on the long main straight and widening it. They also took away the bushes right next to the track at the main straight, which had made that section of the Nürburgring dangerously narrow. A second series of three more F1 races was held until 1976. However, primarily due to its length of over 22 km (14 mi), and the lack of space due to its situation on the sides of the mountains, increasing demands by the F1 drivers and the FIA's CSI commission were too expensive or impossible to meet. For instance, by the 1970s the German Grand Prix required five times the marshals and medical staff as a typical F1 race, something the German organizers were unwilling to provide. Additionally, even with the 1971 modifications it was still possible for cars to become airborne off the track. The Nürburgring was also unsuitable for the burgeoning television market; its vast expanse made it almost impossible to effectively cover a race there. As a result, early in the season it was decided that the 1976 race would be the last to be held on the old circuit.

Niki Lauda, the reigning world champion and only person ever to lap the full 22.835 km (14.189 mi) Nordschleife in under seven minutes (6:58.6, 1975), proposed to the other drivers that they boycott the circuit in 1976. Lauda was not only concerned about the safety arrangements and the lack of marshals around the circuit, he also did not like the prospect of running the race in another rainstorm. Usually when that happened, some parts of the circuit were wet and other parts were dry, which is what the conditions of the circuit were for that race. The other drivers voted against the idea and the race went ahead. Lauda crashed in his Ferrari coming out of the left-hand kink before Bergwerk after a new magnesium component (lighter but more fragile than aluminum used until then) on his Ferrari's rear suspension failed. He was badly burned as his car was still loaded with fuel in lap 2. Lauda was saved by the combined actions of fellow drivers Arturo Merzario, Guy Edwards, Brett Lunger, Emerson Fittipaldi and Harald Ertl.

The crash also showed that the track's distances were too long for regular fire engines and ambulances, even though the "ONS-Staffel" was equipped with a Porsche 911 rescue car, marked (R). The old Nürburgring never hosted another F1 race again, as the German Grand Prix was moved to the Hockenheimring for 1977. The German motorcycle Grand Prix was held for the last time on the old Nürburgring in 1980, also permanently moving to Hockenheim.

By its very nature, the Nordschleife was impossible to make safe in its old configuration. It soon became apparent that it would have to be completely overhauled if there was any prospect of Formula One returning there - the Nürburgring's administration and race organizers were not willing to provide the enormous expense of providing the number of marshals needed for a Grand Prix - up to six times the amount that most other circuits needed. With this in mind, in 1981 work began on a 4.556 km (2.831 mi)-long new circuit, which was built on and around the old pit area.

At the same time, a bypass shortened the Nordschleife to 20.832 km (12.944 mi), and with an additional small pit lane, this version was used for races in 1983, e.g. the 1000km Nürburgring endurance race, while construction work was going on nearby. During qualifying for that race, the late Stefan Bellof set a lap of 6:11.13 for the 20.8 km (12.9 mi) Nordschleife in his Porsche 956, or 199.8 km/h (124.1 mph) on average. This lap held the all-time record for 35 years (partially because no major racing has taken place there since 1984) until it was surpassed by Timo Bernhard in the Porsche 919 Hybrid Evo, which ran the slightly longer version of the circuit in 5:19.546- averaging 233.8 km/h (145.3 mph) on 29 June 2018.

Meanwhile, more run-off areas were added at corners like Aremberg and Brünnchen, where originally there were just embankments protected by Armco barriers. The track surface was made safer in some spots where there had been nasty bumps and jumps. Racing line markers were added to the corners all around the track as well. Also, bushes and hedges at the edges of corners were taken out and replaced with Armco and grass.

The former Südschleife had not been modified in 1970–1971 and was abandoned a few years later in favour of the improved Nordschleife. It is now mostly gone (in part due to the construction of the new circuit) or converted to a normal public road, but since 2005 a vintage car event has been hosted on the old track layout, including part of the parking area.[5]

1984: New Grand Prix track

The new track was completed in 1984 and named GP-Strecke (German: Großer Preis-Strecke: literally, "Grand Prix Course"). It was built to meet the highest safety standards. However, it was considered in character a mere shadow of its older sibling. Some fans, who had to sit much farther away from the track, called it Eifelring, Ersatzring, Grünering or similar nicknames, believing it did not deserve to be called Nürburgring. Like many circuits of the time, it offered few overtaking opportunities.

Prior to the 2013 German Grand Prix both Mark Webber and Lewis Hamilton said they liked the track. Webber described the layout as "an old school track" before adding, "It's a beautiful little circuit for us to still drive on so I think all the guys enjoy driving here." While Hamilton said "It's a fantastic circuit, one of the classics and it hasn't lost that feel of an old classic circuit."[6]

To celebrate its opening, an exhibition race was held on 12 May. The 1984 Nürburgring Race of Champions featured an array of notable drivers driving identical Mercedes 190E 2.3–16's: the line-up was Elio de Angelis, Jack Brabham (Formula 1 World Champion 1959, 1960, 1966), Phil Hill (1961), Denis Hulme (1967), James Hunt (1976), Alan Jones (1980), Jacques Laffite, Niki Lauda (1975, 1977)*, Stirling Moss, Alain Prost*, Carlos Reutemann, Keke Rosberg (1982), Jody Scheckter (1979), Ayrton Senna*, John Surtees (1964) and John Watson. [Drivers marked with * won the Formula 1 World Championship subsequent to the race]. Senna won ahead of Lauda, Reutemann, Rosberg, Watson, Hulme and Jody Scheckter, being the only one to resist Lauda's performance who – having missed the qualifying – had to start from the last row and overtook all the others except Senna.[7][8] There were nine former and two future Formula 1 World Champions competing, in a field of 20 cars with 16 Formula 1 drivers; the other four were local drivers: Klaus Ludwig, Manfred Schurti, Udo Schütz and Hans Herrmann.

Besides other major international events, the Nürburgring has seen the brief return of Formula One racing, as the 1984 European Grand Prix was held at the track, followed by the 1985 German Grand Prix. As F1 did not stay, other events were the highlights at the new Nürburgring, including the 1000km Nürburgring, DTM, motorcycles, and newer types of events, like truck racing, vintage car racing at the AvD "Oldtimer Grand Prix", and even the "Rock am Ring" concerts.

Following the success and first world championship of Michael Schumacher, a second German F1 race was held at the Nürburgring between 1995 and 2006, called the European Grand Prix, or in 1997 and 1998, the Luxembourg Grand Prix.

For 2002, the track was changed, by replacing the former "Castrol-chicane" at the end of the start/finish straight with a sharp right-hander (nicknamed "Haug-Hook"), in order to create an overtaking opportunity. Also, a slow Omega-shaped section was inserted, on the site of the former kart track. This extended the GP track from 4.556 to 5.148 km (2.831 to 3.199 mi), while at the same time, the Hockenheimring was shortened from 6.823 to 4.574 km (4.240 to 2.842 mi).

Both the Nürburgring and the Hockenheimring events have been losing money due to high and rising Formula One license fees charged by Bernie Ecclestone and low attendance due to high ticket prices;[9][10][citation needed] starting with the 2007 Formula One season, Hockenheim and Nürburgring alternated in hosting the German GP.

In Formula One, Ralf Schumacher collided with his teammate Giancarlo Fisichella and his brother at the start of the 1997 race which was won by Jacques Villeneuve. In 1999, in changing conditions, Johnny Herbert managed to score the only win for the team of former Ringmeister Jackie Stewart. One of the highlights of the 2005 season was Kimi Räikkönen's spectacular exit while in the last lap of the race, when his suspension gave way after being rattled lap after lap by a flat-spotted tyre that was not changed due to the short-lived 'one set of tyres' rule.

Prior to the 2007 European Grand Prix, the Audi S (turns 8 and 9) was renamed Michael Schumacher S after Michael Schumacher. Schumacher had retired from Formula One the year before, but returned in 2010, and in 2011 became the second Formula One driver to drive through a turn named after them (after Ayrton Senna driving his "S for Senna" at Autódromo José Carlos Pace).

Alternation with Hockenheim

In 2007, the FIA announced that Hockenheimring and Nürburgring would alternate with the German Grand Prix with Nürburgring hosting in 2007. Due to name-licensing problems, it was held as the European Grand Prix that year. In 2014, the new owners of the Nürburgring were unable to secure a deal to continue hosting the German Grand Prix in the odd-numbered years, so the 2015 and 2017 German Grands Prix were cancelled.

Return of Formula One

In July 2020, it was announced that after seven years, the race track would be an official Formula One Grand Prix with the event taking place from 9 to 11 October 2020. This race was called the Eifel Grand Prix in honour of the nearby mountain range, meaning the venue held a Grand Prix under a fourth different name having hosted races under the German, European and Luxembourg Grands Prix titles previously.[11] That race was won by Lewis Hamilton, who equalled Michael Schumacher's record of wins.

Fatal accidents

While it is unusual for deaths to occur during sanctioned races, there are many accidents and several deaths each year during public sessions. It is common for the track to be closed several times a day for cleanup, repair, and medical intervention. While track management does not publish any official figures, several regular visitors to the track have used police reports to estimate the number of fatalities as between 3 and 12 in a full year.[12] Jeremy Clarkson noted in Top Gear in 2004 that "over the years this track has claimed over 200 lives".[13][unreliable source?]

This article is missing information about the GP-Strecke. (May 2023) |

Nordschleife racing today

Several touring car series still compete on the Nordschleife, using either only the simple 20.830 km (12.943 mi) version with its separate small pit lane, or a combined 25.378 km (15.769 mi)-long track that uses a part of the original modern F1 track (without the Mercedes Arena section, which is often used for support pits) plus its huge pit facilities. Entry-level competition requires a regularity test (GLP) for street-legal cars. Two racing series (RCN/CHC and VLN) compete on 15 Saturdays each year, for several hours.

The annual highlight is the 24 Hours Nürburgring weekend, held usually in mid-May, featuring 220 cars – from small 100 hp (75 kW) cars to 700 hp (520 kW) Turbo Porsche cars or 500 hp (370 kW) factory race cars built by BMW, Opel, Audi, and Mercedes-Benz, over 700 drivers (amateurs and professionals), and up to 290,000 spectators.

As of 2015 the World Touring Car Championship holds the FIA WTCC Race of Germany at the Nordschleife as a support category to the 24 Hours.

BMW Sauber's Nick Heidfeld made history on 28 April 2007 as the first driver in over thirty years to tackle the Nürburgring Nordschleife track in a contemporary Formula One car.[14] Heidfeld's three laps in an F1.06 were part of festivities celebrating BMW's contribution to motorsport. About 45,000 spectators showed up for the main event, the third four-hour VLN race of the season. Conceived largely as a photo opportunity, the lap times were not as fast as the car was capable of, BMW instead needing to run the chassis at a particularly high ride height to allow for the Nordschleife's abrupt gradient changes and to limit maximum speeds accordingly. Former F1 driver Hans-Joachim Stuck was injured during the race when he crashed his BMW Z4.

As part of the festivities before the 2013 24 Hours Nürburgring race, Michael Schumacher and other Mercedes-Benz drivers took part in a promotional event which saw Schumacher complete a demonstration lap of the Nordschleife at the wheel of a 2011 Mercedes W02.[15] As with Heidfeld's lap, and also partly due to Formula One's strict in-season testing bans, the lap left many motorsport fans underwhelmed.[16]

Nordschleife

Since its opening in 1927, the track has been used by the public for the so-called Touristenfahrten: anyone with a road-legal car or motorcycle, as well as tour buses, motor homes, or cars with trailers, are able to access the Nordschleife. It is opened every day of the week, except when races take place. The track may be closed for weeks during the winter months, depending on weather conditions and maintenance work. Passing on the right is prohibited, and some sections have speed limits; the normal traffic rules (StVO in German) apply also here.

The Nürburgring is a popular attraction for many driving enthusiasts and riders from all over the world, partly because of its history and the challenge it provides. The lack of oncoming traffic and intersections sets it apart from regular roads, and the absence of a blanket speed limit is a further attraction.

Normal ticket buyers on tourist days cannot quite complete a full lap of the 20.832 km (12.944 mi) Nordschleife, which bypasses the modern GP-Strecke, as they are required to slow down and pass through a 200-metre (220 yd) "pit lane" section where toll gates are installed. On busier days, a mobile ticket barrier is installed on the main straight in order to reduce the length of queues at the fixed barriers. This is open to all ticket holders. On rare occasions, it is possible to drive both the Nordschleife and the Grand Prix circuit combined.

Drivers interested in lap times often time themselves from the first bridge after the barriers to the last gantry (aka Bridge-to-Gantry or BTG time) before the exit.[17] However, the track's general conditions state that any form of racing, including speed record attempts, is forbidden.[18] The driver's insurance coverage may consequently be voided, leaving the driver fully liable for damage. Normal, non-racing, non-timed driving accidents might be covered by driver's insurance, but it is increasingly common for insurers to insert exclusion clauses that mean drivers and riders on the Nürburgring only have third-party coverage[19] or are not covered at all.[20]

Drivers who have crashed into the barriers, suffered mechanical failure or been otherwise required to be towed off track during Touristenfahrten sessions are referred to as having joined the "Bongard Club". This nickname is derived from the name of the company which operates the large yellow recovery flatbed trucks which ferry those unfortunate drivers and their vehicles to the nearest exit.[21] Due to the high volume of traffic, there is an emphasis on quickly clearing and repairing any compromised safety measures so the track can be immediately re-opened for use.

Additionally, those found responsible for damage to the track or safety barriers are required to pay for repairs, along with the time and cost associated with personnel and equipment to address those damages, making any accident or breakdown a potentially expensive incident. Because it is technically operated as a public toll road, failing to report an accident or instance where track surfaces are affected is considered unlawfully leaving the scene of an accident.[22] This is all part of the rules and regulations which aim to ensure a safe experience for all visitors to the track.

Südschleife

The entire Nürburgring Gesamtstrecke was open to the public from its initial opening. At several points around the circuit there were access roads and toll points from which drivers and riders could begin or end a drive. The Südschleife had one of these at the bottom of the uphill stretch near Müllenbach.

Production car testing

For decades, automotive media outlets and manufacturers have used lap times on the Nordschleife as a standard to measure the performance of production vehicles. A car's time on the circuit is commonly used as a benchmark for its overall performance, and cars from disparate marques or time periods may be directly compared via their lap times. Since 2019, two times have been recorded: one for the whole length of the track, and another for a traditional, slightly truncated layout. Nordschleife test cars are piloted by experienced test drivers with intricate knowledge of the circuit, and are often variants specially prepared for circuit racing, as is the case with the Lexus LFA's "Nürburgring package."[23][24][25]

For sixteen weeks per year, the "industry pool" (Industrie-Pool) rents exclusive daytime use of the track for automotive development and endurance testing.[26] As of 2017[update] the industry pool consisted of approximately 30 car manufacturers, associations, and component suppliers.[26] By 2019, the track was being rented by the industry pool for 18 weeks per year.[27]

Some journalists have opined that Nordschleife testing is deleterious to a car's normal driving experience, producing cars that have sacrificed comfort and driveability in favor of better lap times.[23] Former Top Gear host James May, who is known for his open dislike of testing run on the track,[28][29] has claimed that the Nürburgring prompts designers to focus on a car's grip at the expense of pleasant-feeling handling, and creates cars that are ill-suited for real-world driving conditions.[30] Others have expressed concern over the relevance of these test laps, which lack independent verification and may be conducted using cars significantly different from stock. Porsche is reported as having tried (and failed) to replicate the Nissan GT-R Nismo's record-breaking lap, preparing its own GT-R test car for the task, and the Lamborghini Huracán Performante's time was met with incredulity even after Lamborghini provided video documentation.[25][31]

Television and games

The TV series Top Gear sometimes used the Nordschleife for its challenges, often involving Sabine Schmitz. The first corner of the Nordschleife loop was renamed as the "Sabine-Schmitz-Kurve" in Schmitz's honor after she died of cancer in 2021.[32] In addition, during series 17 (summer 2011) of Top Gear, James May was very critical of the ride quality of cars whose development processes included testing on the Nordschleife, saying that cars which were tested at Nordschleife got ruined.

Multiple layouts of the Nürburgring have been featured in video games, such as the Gran Turismo series, the Forza Motorsport series, the Need for Speed: Shift series, iRacing and Assetto Corsa. Grand Prix Legends, a historic racing simulator also included the Nürburgring on its roster of default Grand Prix tracks.

Leisure development

Other pastimes are hosted at the Nürburgring, such as the Rock am Ring, Germany's biggest rock music festival, attracting close to 100,000 rock fans each year since 1985. Since 1978, the Nordschleife is also the venue of a major running event (Nürburgring-Lauf/Run am Ring). In 2003, a major bicycling event (Rad am Ring) was added and it became the multi-sports event Rad & Run am Ring.

In 2009, new commercial areas opened, including a hotel and shopping mall. In the summer of 2009, ETF Ride Systems opened a new interactive dark ride application called "Motor Mania" at the racetrack, in collaboration with Lagotronics B.V.[33] The roller coaster "ring°racer" was scheduled to open in 2011 however was delayed significantly due to technical issues. It eventually opened October 31, 2013 however closed after just four days of operation on November third.[34]

Ownership

In 2012, the track was preparing to file for bankruptcy as a result of nearly $500 million in debts and the inability to secure financing.[35] On 1 August 2012, the government of Rheinland-Pfalz guaranteed $312 million to allow the track to meet its debt obligations.[36]

In 2013, the Nürburgring was for sale for US$165 million (€127.3 million).[37] The sale process was by sealed-bid auction with an expected completion date of "Late Summer". This meant there was to be a new owner in 2013, unencumbered by the debts of the previous operation, with the circuit expected to return to profitability.[38]

On 11 March 2014 it was reported that the Nürburgring was sold for 77 million euros ($106.8 million). Düsseldorf-based Capricorn Development was the buyer. The company was to take full ownership of the Nürburgring on 1 January 2015.[39] But in October 2014, Russian billionaire, the chairman of Moscow-based Pharmstandard, Viktor Kharitonin, bought a majority stake in the Nürburgring.[40]

In May 2015, the Nürburgring was set to hold the first Grüne Hölle Rock festival as a replacement for the Rock am Ring festival,[41] but the project did not take place. Grüne Hölle Rock changed their name to Rock im Revier and the event was held in the Schalke area.[42]

Nordschleife

| Location | Nürburg, Germany |

|---|---|

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) CEST (DST) |

| Coordinates | 50°20′08″N 6°56′51″E |

| Website | https://nuerburgring.de |

The Nordschleife operates in a clockwise direction, and was formerly known for its abundance of sharp crests, causing fast-moving, firmly-sprung racing cars to jump clear off the track surface at many locations.

Flugplatz ("air field", a small airport)

Although by no means the most fearsome, Flugplatz is perhaps the most aptly (although coincidentally) named and widely remembered section. The name of this part of the track comes from a small airfield, which in the early years was located close to the track in this area. The track features a very short straight that climbs sharply uphill for a short time, then suddenly drops slightly downhill, and this is immediately followed by two very fast right-hand kinks. Chris Irwin's career was ended following a massive accident at Flugplatz, in a Ford 3L GT sports car in 1968. Manfred Winkelhock flipped his March Formula Two car at the same corner in 1980. This section of the track was renovated in 2016[43] after an accident in which Jann Mardenborough's Nissan GT-R flew over the fence and killed a spectator.[44] The Flugplatz is one of the most important parts of the Nürburgring because after the two very fast right-handers comes what is possibly the fastest part of the track: a downhill straight called Kottenborn, into a very fast curve called Schwedenkreuz (Swedish Cross). Drivers are flat out for some time here.

Right before Flugplatz is Quiddelbacher-Höhe (peak, as in "mountain summit"), where the track crosses a bridge over the Bundesstraße 257.

Fuchsröhre ("Fox Hole")

The Fuchsröhre is soon after the very fast downhill section succeeding the Flugplatz. After negotiating a long right-hand corner called Aremberg (which is after Schwedenkreuz) the road goes under a bridge Postbrucke as it plunges downhill, and the road switches back left and right and finding a point of reference for the racing line is difficult. This whole sequence is flat out and then, the road climbs sharply uphill. The road then turns left and levels out at the same time; this is one of the many jumps of the Nürburgring where the car goes airborne. This leads to the Adenauer Forst (forest) turns. The Fuchsröhre is one of the fastest and most dangerous parts of the Nürburgring because of the extremely high speeds in such a tight and confined place; this part of the Nürburgring goes right through a forest and there is only about 2–3 metres (6.6–9.8 ft) of grass separating the track from Armco barrier, and beyond the barriers is a wall of trees.

Bergwerk ("Mine")

Perhaps the most notorious corner on the long circuit, Bergwerk has been responsible for some serious and sometimes fatal accidents.[45][46] A tight right-hand corner, coming just after a long, fast section and a left-hand kink on a small crest, was where Carel Godin de Beaufort fatally crashed. The fast kink was also the scene of Niki Lauda's infamous fiery accident during the 1976 German Grand Prix. This left kink is often referred to as the Lauda-Links (Lauda left). The Bergwerk, along with the Breidscheid/Adenauer Bridge corners before it, are one of the series of corners that make or break one's lap time around the Nürburgring because of the fast, lengthy uphill section called Kesselchen (Little Valley) that comes after the Bergwerk.

Caracciola Karussell ("Carousel")

Although being one of the slower corners on the Nordschleife, the Karussell is perhaps its most famous and one of its most iconic- it is one of two berm-style, banked corners on the track. Soon after the driver has negotiated the long uphill section after Bergwerk and gone through a section called Klostertal (Monastery Valley), the driver turns right through a long hairpin, past an abandoned section called Steilstrecke (Steep Route) and then goes up another hill towards the Karrusell. The entrance to the corner is blind, although Juan Manuel Fangio is reputed to have advised a young driver to "aim for the tallest tree," a feature that was also built into the rendering of the circuit in the Gran Turismo 4 and Grand Prix Legends video games. Once the driver has reached the top of the hill, the road then becomes sharply banked on one side and level on the other- this banking drops off, rather than climbing up like most bankings on circuits. The sharply banked side has a concrete surface, and there is a foot-wide tarmac surface on the bottom of the banking for cars to get extra grip through the very rough concrete banking. Cars drop into the concrete banking, and keep the car in the corner (which is 210 degrees, much like a hairpin bend) until the road levels out and the concrete surface becomes tarmac again. This corner is very hard on the driver's wrists and hands because of the prolonged bumpy cornering the driver must do while in the Karrusell. Usually, cars come out of the top of the end of the banking to hit the apex that comes right after the end of the Karrusell.

The combination of a recognisable corner, slow-moving cars, and the variation in viewing angle as cars rotate around the banking, means that this is one of the circuit's most popular locations for photographers. It is named after German pre-WWII racing driver Rudolf Caracciola, who reportedly made the corner his own by hooking the inside tires into a drainage ditch to help his car "hug" the curve. As more concrete was uncovered and more competitors copied him, the trend took hold. At a later reconstruction, the corner was remade with real concrete banking, as it remains to this day.

Shortly after the Karussell is a steep section, with gradients in excess of 16%, leading to a right-hander called Hohe Acht, which is some 300 m higher in altitude than Breidscheid.[47]

Brünnchen ("Small Well")

A favourite spectator vantage point, the Brünnchen section is composed of two right-hand corners and a very short straight. The first corner goes sharply downhill and the next, after the very short downhill straight, goes uphill slightly. This is a section of the track where on public days, accidents happen particularly at the blind uphill right-hand corner. Like almost every corner at the Nürburgring, both right-handers are blind. The short straight used to have a steep and sudden drop-off that caused cars to take off and a bridge that went over a pathway; these were taken out and smoothed over when the circuit was rebuilt in 1970 and 1971. The uphill right-hand corner is often referred to as "Youtube corner", because of the large number of videos featuring a perspective of that corner.

Pflanzgarten ("Planting Garden") and Stefan Bellof S ("Stefan Bellof Esses")

The Pflanzgarten, which is soon after the Brünnchen, is one of the fastest, trickiest and most difficult sections of the Nürburgring. It is full of jumps, including two huge ones, one of which is called Sprunghügel (Jump Hill). This very complex section is unique in that it is made up of two different sections; getting the entire Pflanzgarten right is crucial to a good lap time around the Nürburgring. This section was the scene of Briton Peter Collins's fatal accident during the 1958 German Grand Prix, and the scene of a number of career-ending accidents in Formula One in the 1970s —Britons Mike Hailwood and Ian Ashley were two victims of the Pflanzgarten.

Pflanzgarten 1 is made up of a slightly banked, downhill left-hander which then suddenly switches back left, then right. Then immediately, giving the driver nearly no time to react (knowledge of this section is key) the road drops away twice: the first jump is only slight, then right after (somewhat like a staircase) the road drops away very sharply which usually causes almost all cars to go airborne at this jump; the drop is so sudden. Then, immediately after the road levels out very shortly after the jump and the car touches the ground again, the road immediately and suddenly goes right very quickly and then right again; this is what makes up the end of the first Pflanzgarten- a very fast multiple apex sequence of right-hand corners.

The road then goes slightly uphill and then through another jump; the road suddenly drops away and levels out and at the same time, the road turns through a flat-out left-hander. Then, the road drops away again very suddenly, which is the second huge jump of the Pflanzgarten known as the Sprunghügel. The road then goes downhill then quickly levels out, then it goes through a flat-out right-hander and this starts the Stefan Bellof S (named as such because Bellof crashed a Porsche 956 there during the 1983 Nurburgring 1000 km), which was known as Pflanzgarten 2 prior to 2013. The Stefan Bellof S is very tricky because the road quickly switches back left and right—a car is going so fast through here that it is like walking on a tightrope. It is very difficult to find the racing line here because the curves come up so quickly, so it is hard to find any point of reference. Then, after a jump at the end of the switchback section, it goes through a flat-out, top gear right-hander and into a short straight that leads into two very fast curves called the Schwalbenschwanz (Swallow's Tail).

The room for error on every part of the consistently high-speed Pflanzgarten and the Stefan Bellof S is virtually non-existent (much like the entire track itself). The road and the surface of the Pflanzgarten and the Stefan Bellof S moves around unpredictably; knowledge of this section is key to getting through cleanly.

Schwalbenschwanz/Kleines Karussell ("Swallow's Tail"/"Little Carousel")

The Schwalbenschwanz is a sequence of very fast sweepers located after the Stefan Bellof S. After a short straight, there is a very fast right-hand sweeper that progressively goes uphill, and this leads into a blind left-hander that is a bit slower. The apex is completely blind, and the corner then changes gradient a bit; it goes up then down, which leads into a short straight that ends at the Kleines Karussell. Originally, this part had a bridge that went over a stream and was very bumpy; this bridge was taken out and replaced with a culvert (large industrial pipe) so that the road could be smoothed over.

The Kleines Karussell is similar to its bigger brother, except that it is a 90-degree corner instead of 210 degrees, and is faster and slightly less banked. Once this part of the track is dealt with, the drivers are near the end of the lap; with two more corners Galgenkopf to negotiate before the 2.135 km (1.327 mi) long Döttinger Höhe straight.

Südschleife layout

The Nürburgring Südschleife | |

| Location | Nürburg, |

|---|---|

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) CEST (DST) |

| Opened | 1927 |

| Closed | 1982 |

| Website | https://nuerburgring.de |

The Nürburgring Südschleife (south loop) was a motor racing circuit which was built in 1927 at the same time as the Nordschleife.

The Südschleife and Nordschleife layouts were joined together by the Start und Ziel (start/finish) area, and could therefore be driven as one track that was over 28.265 km (17.563 mi) long. Races were held at the combined layout only until 1931. The Südschleife was used for the ADAC Eifelrennen from 1928 until 1931 and from 1958 until 1968, as well as for the Eifelpokal and other minor races.

The Südschleife was rarely used after the Nordschleife was rebuilt and updated in 1970 and 1971, and was finally destroyed by the building of the current Nürburgring Grand Prix circuit in the early 1980s. Today only small sections of the original track remain.

Track description

The shared start/finish area of the Nürburgring complex consisted of two back-to-back straights joined together at the southern end by a tight loop. The entrance to the 7.747 km (4.814 mi) Südschleife lay on the outside edge of this hairpin and was signposted as the road to Bonn. It immediately dropped sharply downhill and under a public road before winding through a heavily-wooded section.

Tight corners soon gave way to fast downhill sections with flowing bends until, at the outskirts of the nearby town of Müllenbach, the track turned sharply right northwards and began a long climb up the hill.

At the end of this run came a right hairpin turn which led to a long left curve around the bottom of a hill. This led onto the back straight of the start/finish area. At this point it was possible to continue onto the Nordschleife or take two sharp right-hand turns in order to enter the starting straight once again.

Photographs of the track in use show that trees and hedges were not cut back in many areas, being allowed to grow right up to the trackside. Although the Nordschleife had very little in the way of run-off areas, the Südschleife seems to have had none at all, which was likely to have been a factor in the choice of circuit for major events.

Sections of routes

| km | Section |

|---|---|

| 0 | Start and finish |

| Connection south sweep | |

| 1 | |

| Bränkekopf | |

| 2 | Aschenschlag |

| Seifgen | |

| 3 | |

| Bocksberg | |

| 4 | Müllenbach |

| Rassrück | |

| 5 | |

| Scharfer Kopf | |

| 6 | |

| Gegengerade | |

| 7 | |

| Nordkehre | |

| 7,747 | Start and finish |

The route sections bore the following names, among others Bränkekopf, Aschenschlag, Seifgen, Bocksberg, Müllenbach und Scharfer Kopf.

Stichstraße shortcut

In 1938 a small section of new track (the Stichstraße) was laid which allowed drivers nearing the end of the Südschleife to bypass the start/finish straights and take a right turn which led back to the start of the downhill twists. This shortened a lap to around 5.7 km (3.5 mi). This layout was used for tourist rides and for testing.

Remaining sections

The current Grand Prix circuit required the complete destruction of the start/finish area but at a point around 1 km (0.62 mi) into the Südschleife, a modern public road now follows the route, although the bends have been eased and the vegetation does not come as close to the road as it did when the track was open.

This public road continues into the town of Müllenbach but leaves the route of the old track on the outskirts. Nothing remains of the famous corners there.

The road up the hill still exists and is sometimes used to allow access to parking areas for the Grand Prix track. The lower sections are no longer maintained.

Surviving sections, and the parking lots, are still used in competition. The Cologne-Ahrweiler Rally often uses the Südschleife in competition.[48]

Layout history

Current circuit configurations

- Grand Prix Circuit (2002–present)

- Sprint Circuit (2002–present)

- Müllenbach Circuit (2002–present)

- Combined GP Circuit with Mercedes-Arena (2002–present)

- 24 Hours Circuit (Combined GP Circuit without Mercedes-Arena) (2002–present)

- Combined Sprint Circuit with Mercedes-Arena (2002–present)

- Nordschleife (1983–present)

- Rallycross Circuit (2021–present)

Previous configurations

- Nordschleife (1927–1966)

- Gesamtstrecke (1927–1966)

- Südschleife (1927–1973)

- Nordschleife (1967–1982)

- Gesamtstrecke (1967–1973)

- Südschleife (1973–1982)

- Betonschleife (1927–1982)

- Grand Prix Circuit (1984–1994)

- Comparison between Nordschleife and Grand Prix Circuit (1984–1994)

- Grand Prix Circuit with F1 Chicane (1995–2001)

- Comparison between Nordschleife and Grand Prix Circuit (1995–2001)

- Karting Circuit (1995–2001)

- 24 Hours Circuit (1984–2001)

- Rallycross Circuit (1991–1997)

Nürburgring Nordschleife

As of May 2023, the fastest official race lap records at the Nürburgring Nordschleife are listed as:

Nürburgring Südschleife

The fastest official race lap records on the Südschleife are listed as:

| Category | Time | Driver | Vehicle | Event |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Südschleife: 7.747 km (1927–1982) | ||||

| Group 7 | 2:38.600[86] | Helmut Kelleners | March 707 | 1970 Internationales AvD - SCM-Rundstrecken-Rennen Aachen Nürburgring |

| Group 5 | 2:43.200[87] | Jürgen Neuhaus [de] | Porsche 917 Spyder | 1971 6th International 300 km race |

| Formula Two | 2:47.000[88] | Brian Redman | Lola T100 | 1968 Eifelrennen |

| Group 4 | 3:01.800[89] | Paul Hawkins | Ford GT40 | 1968 Internationales ADAC-Eifelpokal-Rennen Nürburgring |

| Group 3 | 3:28.100[90] | Jürgen Neuhaus [de] | Porsche 911 S | 1967 ADAC-Hansa-Pokal-Rennen Nürburgring |

Modern Nürburgring

As of October 2023, the fastest official lap records at the modern Nürburgring circuit layouts are listed as:

Lap times recorded on the Nürburgring Nordschleife are published by several manufacturers. They are published and discussed in print media, and online.

- For lap times from various sources, see Nürburgring lap times.

- For lap times in official racing events, on several track variants from 20.830 km (12.943 mi) up to 25.947 km (16.123 mi) see List of Nordschleife lap times (racing).

The lap record on the Südschleife is held by Helmut Kelleners with 2:38.6 minutes = 175.85 km/h (109.27 mph), driven with a March 707 in the CanAm run of the 3rd International AvD SCM circuit race on 18 October 1970.[202] Previous record holder was Brian Redman, who achieved 2:47.0 minutes = 161.03 km/h (100.06 mph) in the Formula 2 race on 21 April 1968 with a Ferrari.[203]

- Formula racing

- ADAC Formula 4 (2015–2022)

- Auto GP (2001–2004, 2007, 2013–2014)

- BOSS GP (2007–2008, 2010, 2012, 2024)

- European Formula Two Championship (1967–1973, 1975–1983)

- FIA Formula 3 European Championship (2012–2018)

- Formula 3 Euro Series (2003–2012)

- Formula One

- Formula Renault Eurocup (2006–2009, 2011–2012, 2014–2015, 2017–2020)

- International Formula 3000 (1992–1993, 1996–2004)

- GP2 Series (2005–2007, 2009, 2011, 2013)

- GP3 Series (2011, 2013)

- World Series Formula V8 3.5 (2006–2009, 2011–2012, 2014–2015, 2017)

- Sports car racing

- 6 Hours of Nürburgring / 1000 km Nürburgring (1953, 1956–1991, 2000, 2004–2017)

- 24 Hours Nürburgring (1970–present)

- ADAC GT Masters (2007–present)

- BPR Global GT Series (1995–1996)

- European Le Mans Series (2004–2009)

- FIA GT Championship (1997, 2001)

- FIA GT1 World Championship (2010, 2012)

- FIA Sportscar Championship (1998–2001)

- FIA World Endurance Championship (2015–2017)

- GT World Challenge Europe (2013–2016, 2019–2021, 2023–present)

- International GT Challenge (2024)

- International GT Open (2010, 2012–2014)

- Lamborghini Super Trofeo Europe (2012–2021, 2023–present)

- Porsche Supercup (1995–2007, 2009, 2011, 2013)

- Renault Sport Trophy (2015)

- Veranstaltergemeinschaft Langstreckenpokal Nürburgring (1977–present)

- World Sportscar Championship (1953, 1956–1984, 1986–1991)

- Touring car racing

- Deutsche Tourenwagen Masters (2000–present)

- Deutsche Tourenwagen Meisterschaft (1984–1996)

- European Touring Car Championship (1963–1980, 1982–1986, 1988, 2001)

- European Touring Car Cup (2016–2017)

- NASCAR Whelen Euro Series (2014)

- Super Tourenwagen Cup (1994–1999)

- TCR Europe Touring Car Series (2016, 2021–2022)

- TCR Germany Touring Car Championship (2016–2022, 2024)

- World Touring Car Championship FIA WTCC Race of Germany (1987, 2015–2017)

- World Touring Car Cup FIA WTCR Race of Germany (2018–2022)

- Motorcycle racing

- FIM Endurance World Championship (1977–1985, 2001)

- Grand Prix motorcycle racing German motorcycle Grand Prix (1955, 1958, 1965, 1968, 1970, 1972, 1974, 1976, 1978, 1980, 1984, 1986, 1988, 1990, 1995–1997)

- Sidecar World Championship (1955, 1958, 1965, 1968, 1970, 1972, 1974, 1976, 1978, 1980, 1984, 1986, 1988, 1990, 1995–1997, 1999, 2005)

- Superbike World Championship (1998–1999, 2008–2013)

- Rallycross racing

- FIA World Rallycross Championship World RX of Germany (2021–2022)

- Cycling

- UCI Road World Championships (1927, 1966, 1978)

- Rad am Ring (2003–present)

2024 events

- March 23: Nürburgring Endurance Series

- April 6: Nürburgring Endurance Series

- May 4: Nürburgring Endurance Series

- May 24–26: BOSS GP Nürburgring Classic

- June 1–2: Intercontinental GT Challenge Nürburgring 24 Hours

- June 7–9: Rock am Ring

- June 15–16: Porsche Sports Cup Deutschland [de]

- June 22: Nürburgring Endurance Series

- June 28–30: TCR Germany Touring Car Championship ADAC Racing Weekend Nürburgring

- July 6: Nürburgring Endurance Series

- July 12–14: FIA European Truck Racing Championship International ADAC Truck-Grand-Prix, ADAC GT Masters

- July 19–21: Rad am Ring

- July 26–28: GT World Challenge Europe, Lamborghini Super Trofeo Europe, French F4 Championship, McLaren Trophy Europe

- August 3: Nürburgring Endurance Series

- August 9–11: Oldtimer Grand Prix

- August 16–18: Deutsche Tourenwagen Masters, Prototype Cup Germany [de], ADAC GT4 Germany, Porsche Carrera Cup Germany

- August 30–September 1: IDM Superbike Championship [de]

- September 5–8: Ferrari Challenge Europe

- September 13–15: Nürburgring Endurance Series

- September 20–22: ADAC 1000 km Revival

- October 3–6: RGB Saisonfinale

- October 11–13: TCR Germany Touring Car Championship ADAC Westfalen Trophy

- October 19–20: Nürburgring Drift Cup

The Nürburgring is known for its frequently changing weather. The near-fatal accident of Niki Lauda in 1976 was accompanied by poor weather conditions and also the 2007 Grand Prix race saw an early deluge take several cars out through aquaplaning, with Vitantonio Liuzzi making a lucky escape, hitting a retrieving truck with the rear wing first, rather than the fatal accident that befell Jules Bianchi seven years later at Suzuka. In spite of this reputation, the Nürburg weather station only recorded an average of 679.3 mm (26.74 in) between 1981 and 2010.[204] Contrasting this, the relatively nearby Ardennes racetrack of Spa-Francorchamps in Wallonia, Belgium has a much rainier climate, as can be implied by data from the village hosting the track called Stavelot and the village of Malmedy, through which the circuit passes.

Nürburg has a semi-continental climate with both oceanic and continental tendencies. It does however land in the former category (Köppen Cfb). Due to the Nordschleife's varied terrain and elevation, weather may be completely different on either end of the track. The elevation shift also makes thermal differences a strong possibility. The modern Grand Prix circuit also has sizeable elevation changes between the start-finish straight and the lowest point on the opposite end of the track, but the geographical distance and actual elevation gain between the two are lower. Annual sunshine is in the 1500s, which is low by European standards, but only slightly gloomier than the nearest large city of Cologne located on a plain. Contrasting that, Nürburg has cooler weather year-round due to the higher elevation of the Eifel Mountains than the Rhine Valley.

| Climate data for Nürburg, 485 m asl (1981–2010 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 13.5 (56.3) |

15.6 (60.1) |

20.7 (69.3) |

25.8 (78.4) |

30.4 (86.7) |

33.3 (91.9) |

34.9 (94.8) |

36.0 (96.8) |

30.2 (86.4) |

25.2 (77.4) |

18.8 (65.8) |

12.6 (54.7) |

36.0 (96.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 2.6 (36.7) |

4.3 (39.7) |

7.7 (45.9) |

12.3 (54.1) |

16.4 (61.5) |

19.7 (67.5) |

21.6 (70.9) |

21.4 (70.5) |

17.0 (62.6) |

12.5 (54.5) |

6.6 (43.9) |

2.8 (37.0) |

12.2 (54.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 0.3 (32.5) |

1.6 (34.9) |

4.2 (39.6) |

8.0 (46.4) |

11.9 (53.4) |

15.0 (59.0) |

16.9 (62.4) |

16.6 (61.9) |

13.0 (55.4) |

9.2 (48.6) |

4.3 (39.7) |

0.6 (33.1) |

8.6 (47.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −2.1 (28.2) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

0.7 (33.3) |

3.6 (38.5) |

7.5 (45.5) |

10.1 (50.2) |

12.2 (54.0) |

11.9 (53.4) |

9.0 (48.2) |

5.9 (42.6) |

2.0 (35.6) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

4.9 (40.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −18.6 (−1.5) |

−17.4 (0.7) |

−12.4 (9.7) |

−6.4 (20.5) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

2.1 (35.8) |

5.0 (41.0) |

3.6 (38.5) |

1.1 (34.0) |

−5.3 (22.5) |

−10.8 (12.6) |

−18.1 (−0.6) |

−18.6 (−1.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 48.0 (1.89) |

51.2 (2.02) |

50.6 (1.99) |

47.4 (1.87) |

60.6 (2.39) |

53.8 (2.12) |

68.9 (2.71) |

77.7 (3.06) |

57.0 (2.24) |

54.1 (2.13) |

57.5 (2.26) |

51.5 (2.03) |

678.3 (26.71) |

| Average precipitation days | 9.5 | 10.6 | 10.9 | 9.4 | 9.9 | 9.8 | 11.4 | 9.5 | 9.6 | 10.5 | 12.0 | 10.8 | 123.9 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 56.7 | 72.1 | 116.6 | 166.9 | 187.0 | 205.3 | 204.4 | 193.3 | 147.1 | 105.7 | 46.5 | 43.0 | 1,544.6 |

| Source: Météo Climat [205][206] | |||||||||||||

- List of Nürburgring Nordschleife lap times

- List of Formula One circuits

- Circuit de Spa-Francorchamps (nearby historical circuit in Belgium).

- Eifelrennen

- "Nürburgring Information - ETRC". Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- "Maps of Nürburgring configurations". The Fast Lane. 30 August 2005. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- Eveleigh, Ian (27 July 2009). "Birth of an icon: 1927: The Nürburgring". evo: The Thrill of Driving. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- Vintage Nürburgring vintage-nuerburgring.de. Retrieved 18 October 2007.

- "Some love for the Grand Prix circuit". AUSringers.com. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- "Result list of the Nürburgring Mercedes 190 exhibition race of 12 May 1984". PistonHeads.com. Archived from the original on 16 June 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

- Rallye Racing June 1984. Rallye Racing.

- "German promoter 'not willing to pay F1 hosting fee': Ecclestone". Deutsche Welle. Reuters. 6 March 2015. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- Schrader, Stef (25 February 2015). "Nürburgring Willing To Lose Money To Host The F1 German Grand Prix". Jalopnik. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- "FORMULA 1 ARAMCO EIFEL GRAND PRIX STARTS AT THE NÜRBURGRING". Nuerburgring. 24 July 2020. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- "Nürburgring Warning". Ben Lovejoy. Retrieved 9 July 2008.

- Top Gear series 5, episode 5

- "Nick Heidfeld drives the Nordschleife – part 1". AUSringers.com. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- "VIDEO: Mercedes F1 W02 around the Nordschleife". AUSringers.com. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- "VIDEO: Mercedes-Benz F1 W02 on the Nordschleife". AUSringers.com. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- "Bridge-to-Gantry. Retrieved 2013-04-15". Bridgetogantry.com. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- Andrew Thompson and Co. Archived 14 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine on Nordschleife insurance

- Admiral insurance policy, page 20: "We will not cover you or be liable for [...] Any accident, injury, loss, theft, or damage which takes place while your car is: [...] used on the Nurburgring Nordschleife [...]"

- "The Bongard Club". www.facebook.com.

- "Driving regulations" (PDF). www.nuerburgring.de. 2015.

- Braun, Peter (3 November 2013). "The Nurburgring - Bad for the performance and bad for the car industry". Digital Trends. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- Stumpf, Rob (19 February 2021). "Here's Why Automakers Are Publishing Two Different Nurburgring Times". The Drive. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- Fallah, Alborz (23 March 2017). "Nurburgring lap times are now meaningless". Drive. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- "Nürburgring is the be-all end-all for auto-manufacturer testing". Autoweek. 17 September 2015.

loose partnership called the Industry Pool, comprising 30 OEMs, nine tire manufacturers, five parts suppliers, and four associations. … rent the 'Ring four days a week, 16 weeks a year (normally two weeks a month between April and October). On those days, the track belongs exclusively to pool members from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. … pool members use Top Line Development, a service that provides drivers for durability testing

- Haupt, Andreas (26 August 2019). "Marketing-Turbo für den Porsche Taycan" [Marketing Turbo for the Porsche Taycan]. Auto motor und sport (in German).

Zusammen im Industrie-Pool für 18 Wochen im Jahr.

- Perkins, Chris (24 August 2016). "Why Cars Developed at the Nurburgring Are Good On the Road". Road & Track. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- Enright, Andy (21 May 2019). "Does the Nürburgring really ruin road cars?". WhichCar. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- May, James (11 June 2009). "Why the 'Ring?". Top Gear Blog. Archived from the original on 14 June 2009.

- Resnicj, Jim (20 October 2017). "Fast and Loose: There's No Oversight for Nurburgring Lap-Time Claims". Car and Driver. Retrieved 31 May 2023.

- Cleeren, Filip (18 June 2021). "Nordschleife corner named after late Nurburgring ace Schmitz". Autosport. Archived from the original on 18 June 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- "Nürburgring – Formula I racetrack". ETF Group. Archived from the original on 8 February 2013. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- "German state guarantees loan for Nürburgring". Autoweek. 1 August 2012. Archived from the original on 4 August 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|agency=ignored (help) - "Race track up for sale". autoblog.com. 18 February 2013. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- "Nürburgring for Sale". ShareTheNurburgring.com. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- DeGroot, Nick (30 October 2014). "Nurburgring sold to Russian billionaire". Motorsport.com.

- "Die "Grüne Hölle" ersetzt Rock am Ring". www.t-online.de. 3 June 2014. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- "Wenn der Vorverkauf zum Festival zweimal startet". www.ksta.de. 8 April 2015. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- nuerburgring.de. ""Grünes Licht" der FIA für Sicherheits-Maßnahmen an der Nordschleife". www.nuerburgring.de (in German). Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- "VLN-Auftaktrennen unfallbedingt abgebrochen". VLN.de (in German). 28 March 2015. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- "Race Cancelled After Fatal Accident". Ausringers.com. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- "Nicka Lauda's crash in 1976". Ausringers.com. Retrieved 7 July 2013.

- "Streckenprofil Nuerburgring Nordschleife". Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- "Black day for motorsport". Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- "June 24, 2013: Dear reader!". Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- "32nd Int. ADAC Zurich 24-hour race - 24-hour race at the Nürburgring". Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- "Sieg und neuer Rundenrekord für Alzen-Motorsport". 24 September 2005. Archived from the original on 22 December 2010. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- "24 Hours of Nürburgring 2003" (PDF). 3 July 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 January 2011. Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- "51. ADAC TotalEnergies 24h Nürburgring Lap by Lap Race" (PDF). 21 May 2023. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- "We attacked, set fastest lap and distance record — "Winner of the 24h Nürburgring/ Nordschleife 2009"". 25 May 2009. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- "37. ADAC Zurich 24h-Rennen 2009". Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- "WTCR 2021 » Nürburgring Round 2 Results". Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- "ETC Cup 2016 » Nürburgring Round 5 Results". Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- "Porsche Supercup 2011 >> Rennergebnis Porsche Supercup Nürburgring Nordschleife". Archived from the original on 1 April 2016. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- "ETC Cup 2016 » Nürburgring Round 6 Results". Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- "VLN: Strycek: New touring car record, but overall victory missed". 11 November 2000. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- "ADAC 24 Stunden Rennen Nürburgring support race". Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- "ADAC Grosser Preis der Tourenwagen, ADAC 24 Stunden Rennen Nürburgring support race". Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- "29. Int. ADAC Zürich Agrippina 24h Rennen". Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- "Nurburgring". Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- "1983 Nurburgring 1000Kms". Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- "1983 Eifelrennen". Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- "1983 Nurburgring German F3". Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- "THAT WAS WILHELM KERN'S SECOND COUP. WITH MARCEL TIEMANN, WINNER OF THE 2ND RUN OF THE LONG-DISTANCE CHAMPIONSHIP". 6 April 2002. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- "1983 Nurburgring ETCC". Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- "1982 Eifelrennen". Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- "Nürburgring 1000 Kilometres 1974". Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- "DRM Nürburgring Eifelrennen 1981". Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- "Nürburgring 1000 Kilometres 1982". Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- "Interserie Nürburgring 1973". Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- "Nürburgring 1000 Kilometres 1981". Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- "DRM Nürburgring Eifelrennen 1982". Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- "Nürburgring 6 Hours 1974". Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- "Nürburgring 1000 Kilometres 1970". Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- "1969 Eifelrennen". Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- "Nürburgring 6 Hours 1970". Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- "Nürburgring 1000 Kilometres 1966". Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- "Nürburgring 1000 Kilometres 1964". Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- "1939 Eifelrennen". Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- "Nürburgring 500 Kilometres 1966". Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- "Nürburgring - Sports, Prototypes and Can-Am 1970". Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- "1971 VI Internationales 300 Km Rennen". Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- "1968 Eifelrennen". Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- "Eifelpokal Nürburgring 1968". Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- "DARM Nürburgring Hansapokal 1967". Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- "2016 FIA WEC 6 Hours of Nürburgring Race Final Classification by Class" (PDF). Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA). 24 July 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- "2009 Nürburgring GP2". Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- "2015 Nürburgring Formula Renault 3.5 Race 2 (40' +1 lap) Final Classification" (PDF). 13 September 2015. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- "2013 Nürburgring GP3 - Round 7". Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- "2017 FIA WEC 6 Hours of Nürburgring Race Final Classification by Class" (PDF). Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA). 16 July 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- "2002 Nürburgring F3000". Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- "2012 F2 Round 6". Retrieved 23 May 2021.

- "DTM 2020 » Nürburgring Grand Prix Round 9 Results". Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- "Formula Le Mans Nürburgring 2009". Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- "Formula Le Mans 2009 standings". Archived from the original on 8 January 2023. Retrieved 1 August 2023.

- "2015 Nürburgring Renault Sport Trophy Prestige Race (25' +1 lap) Final Classification" (PDF). 13 September 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2023.

- "2020 Formula Renault Eurocup Nürburgring Race 2 Statistics". Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- "2021 Nurburgring GT Endurance". Retrieved 3 May 2021.

- "2017 Formula Renault Eurocup Nürburgring Race 1 Statistics". Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- "FIA GT1 World Championship Nürburgring 2010". Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- "2023 Lamborghini Super Trofeo Nürburgring Race 2 Provisional Results" (PDF). 30 July 2023. Retrieved 30 July 2023.

- "ADAC Westfalen Trophy - Finale ADAC Racing Weekend 2022 ADAC Formel 4 Provisional Result Rennen 3" (PDF). 16 October 2022. Retrieved 16 October 2022.

- "2021 Trofeo Pirelli Nürburgring Race 1 (30 Minutes) Final Classification" (PDF). 28 August 2021. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- "2017 Porsche Cup Deutschland Nürburgring (Race 1)". Retrieved 30 October 2022.

- "2005 Formula BMW ADAC Nürburgring (Race 2)". Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- "2012 Nürburgring Eurocup Mégane Trophy Race 1 (40' +1 lap) Final Classification" (PDF). 30 June 2012. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- "FIA GT1 Championship Nürburgring Nürburgring GP-Strecke, Länge: 5148 m. 26. - 29. August 2010 ADAC Formel Masters Ergebnis Rennen 3" (PDF). 29 August 2010. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- "2021 TCR Europe Race 2 Nürburgring" (PDF). 5 September 2021. Retrieved 5 September 2021.

- "2023 Clio Cup Series Nürburgring Race 2 Final Results" (PDF). 30 July 2023. Retrieved 30 July 2023.

- "Nurburgring - RacingCircuits.info". Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- "Nurburgring map, history and latest races - Motorsport Database - Motorsport Magazine". Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- "2015 FIA WEC 6 Hours of Nürburgring Race Final Classification by Class" (PDF). Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA). 30 August 2015. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- "2008 European Le Mans Series Nürburgring". Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- "ADAC Westfalen Trophy - Finale ADAC Racing Weekend - Prototype Cup Germany - Final Result Rennen 2" (PDF). 16 July 2022. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- "Nürburgring, 30-31 August 01 September 2013 Superbike - Results Race 1" (PDF). World Superbike. Dorna. 1 September 2013. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- "2023 Fanatec GT World Challenge Europe Nürburgring Race Final Classification" (PDF). 30 July 2023. Retrieved 30 July 2023.

- "Nürburgring, 30-31 August 01 September 2013 Supersport - Results Race" (PDF). World Superbike. Dorna. 1 September 2013. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- "AvD-Oldtimer-Grand-Prix 2020" (PDF). 9 August 2020. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- "2023 Lamborghini Super Trofeo Nürburgring Race 1 Provisional Results" (PDF). 29 July 2023. Retrieved 30 July 2023.

- "2012 Nürburgring ADAC Formel Masters Result List Race 2" (PDF). 16 September 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- "Nürburgring 1000 Kilometres 2004". Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- "Blancpain GT World Challenge Europe Round 8 GT4 European Series Race 2 Nürburgring" (PDF). 1 September 2019. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- "AvD-Oldtimer-Grand-Prix 2020" (PDF). 8 August 2020. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- "AvD-Oldtimer-Grand-Prix 2020" (PDF). 8 August 2020. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- "AvD-Oldtimer-Grand-Prix 2018" (PDF). 11 August 2018. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- "AvD-Oldtimer-Grand-Prix 2019" (PDF). 11 August 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- "AvD-Oldtimer-Grand-Prix 2019" (PDF). 11 August 2019. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- "AvD-Oldtimer-Grand-Prix 2019" (PDF). 11 August 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- "British GT Championship Nürburgring 2012". Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- "2020 48. ADAC TOTAL 24h-Rennen ADAC Formel 4 Provisional Result Race 1" (PDF). 25 September 2020. Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- "AvD-Oldtimer-Grand-Prix 2019 R12" (PDF). 11 August 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- "AvD-Oldtimer-Grand-Prix 2019 R3" (PDF). 11 August 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- "AvD-Oldtimer-Grand-Prix 2018 Race 10" (PDF). 12 August 2018. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- "36. ADAC- Zurich 24h-Rennen ADAC Formel Masters Ergebnis Rennen 1" (PDF). 24 May 2008. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- "AvD-Oldtimer-Grand-Prix 2018 Race 3" (PDF). 12 August 2018. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- "AvD-Oldtimer-Grand-Prix 2018 Race 8" (PDF). 12 August 2018. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- "Nurburgring Classic 2017" (PDF). Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- "AvD-Oldtimer-Grand-Prix 2019 R6" (PDF). 11 August 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- "AvD-Oldtimer-Grand-Prix 2019 R2" (PDF). 11 August 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- "AvD-Oldtimer-Grand-Prix 2019 R5" (PDF). 10 August 2019. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- "AvD-Oldtimer-Grand-Prix 2016 R7" (PDF). Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- "2014 Nurburgring Auto GP". Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- "2015 Nurburgring European F3 - Round 29". Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- "2004 Nürburgring Euro F3000". Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- "DTM 2019 » Nürburgring Short Round 15 Results". Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- "DTM 2017 » Nürburgring Short Round 14 Results". Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- "34. Int. ADAC Truck Grand Prix Nürburgring Sprint, length 3629 m 19. - 21. July 2019 IDM Superbike 1000 Result Race 1" (PDF). 20 July 2019. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- "2023 ADAC Truck Grand Prix Nürburgring ADAC GT Masters Race 2" (PDF). 16 July 2023. Retrieved 16 July 2023.

- "2018 Nürburgring ADAC Formel 4 Result List Race 1" (PDF). 4 August 2018. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- "Belcar Nürburgring 2002". Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- "DTM Nürburgring Porsche Carrera Cup Deutschland 05 August 2023 Race 1 Nürburgring" (PDF). 5 August 2023. Retrieved 6 August 2023.

- "26. Int. ADAC TRUCK-GRAND-PRIX 08. - 10. Juli 2011 Nürburgring GP - Sprintstrecke, Länge 3629 m ADAC Formel Masters Ergebnis Rennen 1" (PDF). 9 July 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- "2004 Formula BMW ADAC Nürburgring (Race 2)". Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- "2022 ADAC GT4 Germany Race 1 Nürburgring" (PDF). 6 August 2022. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- "2014 Nürburgring 200 Race 1". Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- "TCR DE 2022 » Nürburgring Short Round 8 Results". Retrieved 7 August 2022.

- "2023 DTM Nürburgring - NXT Gen Cup - Race 1" (PDF). 6 August 2023. Retrieved 17 February 2024.

- "35. INT. ADAC TRUCK-GRAND-PRIX Nürburgring, length 3629 m 14.-17. July 2022 Goodyear FIA European Truck Racing Championship Provisional Result Race 1, 16.07.2022" (PDF). 16 July 2022. Retrieved 30 July 2022.

- "35. INT. ADAC TRUCK-GRAND-PRIX Nürburgring, length 3618 m 14.-17. July 2022 Prototype Cup Germany Lap Analysis race 1, 16.07.2022" (PDF). 16 July 2022. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- "2013 Nürburgring ADAC GT Masters Results Race 2" (PDF). 4 August 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- "2017 IDM Nürburgring IDM Superbike 1000 Rennen 2" (PDF). 14 May 2017. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- "2013 Nürburgring ADAC Formel Masters Result List Race 2" (PDF). 4 August 2013. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- "2017 IDM Nürburgring IDM SSP600-STK600 Race 1" (PDF). 13 May 2017. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- "2017 IDM Nürburgring IDM Supersport 300 Rennen 1" (PDF). 14 May 2017. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- "2000 1000 km of Nürburgring Race Results" (PDF). 9 July 2000. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 October 2005. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- "2001 Nürburgring F3000". Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- "SportsRacing World Cup Nürburgring 1999". Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- "FIA GT Championship Nürburgring 1997". Retrieved 3 May 2022.

- "FIA Sportscar Championship Nürburgring 2001". Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- "DTM 2001 » Nürburgring Grand Prix Round 2 Results". Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- "Nürburgring 4 Hours 1996". Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- "FIA GT Championship Nürburgring 2001". Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- "2001 FC Euro Series Nürburgring - 9th September, Round 3". Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- "Porsche Supercup 2000 Round 4: Nürburgring, 21st May". Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- "1992 F3000 Nürburgring Race Statistics". Retrieved 7 December 2022.

- "Interserie Nürburgring 1994". Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- "Nürburgring 1000 Kilometres 1988". Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- "Deutsche Tourenwagen Meisterschaft 1994 » Nürburgring Grand Prix Round 14 Results". Retrieved 7 December 2022.

- "4 h Nürburgring 1998". Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- "STW Cup 1999 » Nürburgring Grand Prix Round 12 Results". Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- "2001 Porsche Cup Deutschland Nürburgring". 6 May 2001. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- "Nürburgring 500 Kilometres 1988". Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- "ADAC GT Cup Nürburgring 1993". Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- "Interserie Nürburgring 1991". Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- "Interserie Nürburgring 2001". Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- "DTM 2001 » Nürburgring Short Round 7 Results". Retrieved 7 December 2022.

- "2001 Porsche Cup Deutschland Nürburgring 2". 26 August 2001. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- "ADAC GT Cup Nürburgring Supersprint 1993". Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- "Interserie Nürburgring Supersprint 1974". Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- "Interserie Nürburgring Supersprint 1975". Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- "Interserie Nürburgring 1982". Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- "DRM Nürburgring Supersprint 1981". Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- "DRM Nürburgring Supersprint 1982". Retrieved 9 December 2022.

- "Rennsport Trophäe Nürburgring Supersprint 1982". Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- "DRM Nürburgring Supersprint 1976". Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- "DRM Nürburgring Supersprint 1977". Retrieved 20 July 2022.

- "3. Int. SCM Rundstreckenrennen 1970". 10 February 2005. Archived from the original on 10 February 2005. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- Behrndt, Michael; Födisch, Jörg-Thomas; Behrndt, Matthias (2009). ADAC-Eifelrennen [die Geschichte der traditionsreichsten Motorsportveranstaltung Deutschlands seit 1922]. Königswinter: Heel. ISBN 978-3-86852-070-5. OCLC 458746509.

- "German climate normals 1981-2010" (in French). Météo Climat. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- "German climate normals 1981-2010" (in French). Météo Climat. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- "Nürburg Weather Extremes" (in French). Météo Climat. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

Notes

Works cited

- Behrndt, Michael, Födisch, Jörg-Thomas: 75 Jahre Nürburgring. Eine Rennstrecke im Rückspiegel. Heel Verlag, Königswinter 2002, ISBN 3-89880-083-0.

- Födisch, Jörg-Thomas; Ostrovsky, Robert (2000), Der Nürburgring : Die legendäre Rennstrecke von 1927 bis heute (in German), Königswinter: Heel, ISBN 3-89365-841-6

- Förster, Wolfgang "Faszination Nürburgring – Gestern und Heute" Heel-Verlag, Königswinter, 2011, ISBN 978-3-86852-496-3.

- Kräling, Ferdi, Messer, Gregor: Grüne Hölle Nürburgring – Faszination Nordschleife. 1. Auflage, Delius Klasing, Bielefeld 2011 ISBN 978-3-7688-3274-8.

- Nixon, Chris (2005). Kings of the Nürburgring: Der Nürburgring: A History 1925-1983. Isleworth, Middlesex, UK: Transport Bookman Publications. ISBN 0851840701.

![]() Media related to Nürburgring at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Nürburgring at Wikimedia Commons