Mavka: The Forest Song – Ukrainian animation echoes the ecocide of wartime

Sometimes I feel that after Chernobyl our land is cursed. Hearing about French children watching Mavka in a Parisian cinema, I felt hope.

Feb. 27, 2024 • 7 min • Source

As a child, I remember watching FernGully: The Last Rainforest (1992) with a sense of horror. I grew up in Ukraine, playing on construction sites, picking up dandelions and cigarette butts on city playgrounds and breathing in the smoke of nearby machine plants. So I felt tremendous sympathy for the forest fairies and was devastated by the scenes of mass tree felling by the evil humans.

I didn’t recognise the dissonance of watching the cartoon in a concrete nine-storey apartment block that had recently risen on the meadows devoured by my city. At the time, I even loved the polluted city more than my grandparents’ idyllic lakeside home. There was more to do on the littered sidewalks, glistening with the multicoloured film of oil byproducts. But a desire for nature to prevail took root.

On a family trip to the forest the weekend that followed, I refused to cut mushrooms and tried to catch a glimpse of magical life under the ferns and occasional pine trees of the Ukrainian steppe. FernGully’s ecological message had prevailed through my concrete-covered childhood.

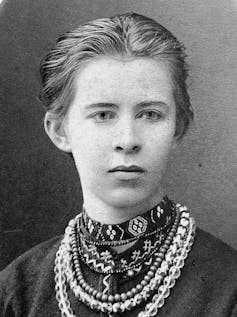

Ukrainian nature has had its own eco-stories. In 1911 Lesya Ukrainka, a young Ukrainian woman who’d spent most of her short life in a sick bed, used her imagination to travel into the wilderness of folklore. She wrote a play, The Forest Song, about Mavka, an eternal forest nymph who falls in love with a young man from the village and finds herself torn between two worlds. Her lover’s family builds a house on the brink of the forest, slowly cultivating it into a field.

In the early 20th century, happy endings were rare in Ukrainian (or, perhaps, any) fiction. Mavka ends up compromising her principles, paying with her blood for allowing humans to cut the ancient trees. She grows disillusioned with humans as her lover trades his musical talents for household comforts, marrying a local widow, who proves better at farming.

Mavka gives her body to “the one-who-sits-in-the-rock”, a spirit of natural vengeance and disasters, and pays her revenge. Her former lover becomes a werewolf and freezes to death under a tree.

Ukrainka depicted the forest as a safeguard of joy and primordial memory of the land. Nature grows increasingly fragile as the old agreements between humans and spirits break.

Adapting The Forest Song

As a child, I was sure that FernGully was an echo of The Forest Song. With one significant difference – in the cartoon the man becomes a positive influence on nature.

The new animated adaptation of Ukrainka’s play, Mavka: The Forest Song, took 10 years to produce. It faced multiple financing problems, not to mention the full-scale invasion of Ukraine by Russia. I feared that the filmmakers might reduce Ukrainka’s story to a Disney-style feel-good tale. I was right.

Spirits became cat-like animal side-kicks and Mavka’s lover became her slightly annoying assistant – and nobody dies in the end.

What surprised me most was the unexpected success of Mavka, both among Ukrainian and international audiences. Watching the animation in Paris, my Ukrainian friends reported roaring laughter and applause from the little French viewers. The animation was screened in 148 countries and dubbed in 32 languages.

Ecocide in Ukraine

The Russo-Ukrainian war has made Ukrainian law recognise ecocide as a crime, punishable by a prison term of up to 15 years.

It is almost inconceivable to imagine the Russian officers who blew up the Kakhovka dam and caused the destruction of thousands of homes being prosecuted in the near future. But Ukrainian eco-activists, biologists and lawyers are determined to bring this question into the international law too.

From the beginning of the invasion, Ukrainians have used animals and nature to engage the world audience. Attention was drawn to the Kakhovka dam through videos of volunteers rescuing animals from the water. Fundraisers organised by the Kharkiv bat activists who save bats affected by the war have attracted international attention.

Nature has become both one of the most painful and most visible reminders of the war. Mavka uses animals in similar fashion, converting “the one-one-who-breaks-dams” (one of Mavka’s love interests in the original play) into Swampy, a “kitty-frog” who follows her every step. It also features a lynx, an endangered species from Chornobyl that has become extremely rare.

I sympathise with this innocent manipulation. The forests where I tried to find FernGully characters as a child have been heavily mined since the occupation of the Kharkiv region in 2022.

Most recently in February 2024 oil byproducts spillage caused by a Russian-Iranian drone, leaked into two of the three Kharkiv city rivers, endangering the water and killing wild ducks and other species.

The same drone attack killed seven people. Yet, it feels almost impossible to interest a world audience with the alien images of a Ukrainian family burnt alive. Nature, however, is something that we all share.

Sometimes I feel that after the Chornobyl disaster our land is cursed by the ancient gods of nature (Mavkas and mermaids) to eternal suffering. Hearing about French children watching Ukrainian Mavka in a Parisian cinema, I felt hope. Perhaps someday they will recall Mavka, like I remembered FernGully, with an understanding that action needs to be taken to make our coexistence with nature more harmonious.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.

Viktoriia Grivina does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.