Solution for remotely monitoring oil wells wins MIT $100K

MIT startup Acoustic Wells earned the grand prize at the annual entrepreneurship competition.

The winner of Wednesday’s MIT $100K Entrepreneurship Competition was a startup helping oil well owners remotely monitor and control the pumping of their wells, increasing production while reducing equipment failures that can lead to methane emissions.

Acoustic Wells, a team including two MIT postdocs, was awarded the grand prize after eight finalist teams pitched their projects to judges and hundreds of attendees at Kresge Auditorium. T-var EdTech, a company developing phonics-based devices that help children learn to read, earned the $10,000 audience choice prize.

The MIT $100K, MIT’s largest entrepreneurship competition, celebrated its 30th anniversary this year and featured talks from $100K co-founder Peter Mui ’82 and MassChallenge founder John Harthorne MBA ’07, who won the $100K grand prize in 2007.

Mui reflected on how much the program has grown since he and his classmates first had the idea in 1989, back when it was the MIT $10K. Harthorne talked about the inspiration he got as an MBA candidate from his MIT classmates tackling some of the world’s biggest problems.

“MIT taught me to dream big, and that’s what this event is all about,” Harthorne said to the crowd at the sold out auditorium. “Every one of the teams competing tonight could go on to do great things.”

Improving oil well pumping

The majority of North America’s 1.4 million oil wells are run by independent owners operating batches of hundreds or thousands of aging wells. Working with thin profit margins and unreliable equipment, the owners rely on small teams of workers to manually inspect each well in a yearlong, labor-intensive process.

When setting up their pumping equipment, each owner must strike a balance: If they set up the wells to pump too slowly, they risk leaving oil in the ground and losing much-needed revenue. If they pump too fast, they risk breaking their equipment and causing pollution.

“The result [of pumping too fast] is similar to when you’re drinking with a straw from a cup and there’s nothing left, so you hear that bubble sound,” Acoustic Wells co-founder and CEO Sebastien Mannai SM ’14 PhD ’18 told the audience. “The same thing happens with oil wells, but on a much bigger scale.”

In the case of oil wells, those “bubbles” are pockets of methane that enter the pump and cause it to fail, unleashing unnecessary greenhouse gases in the process.

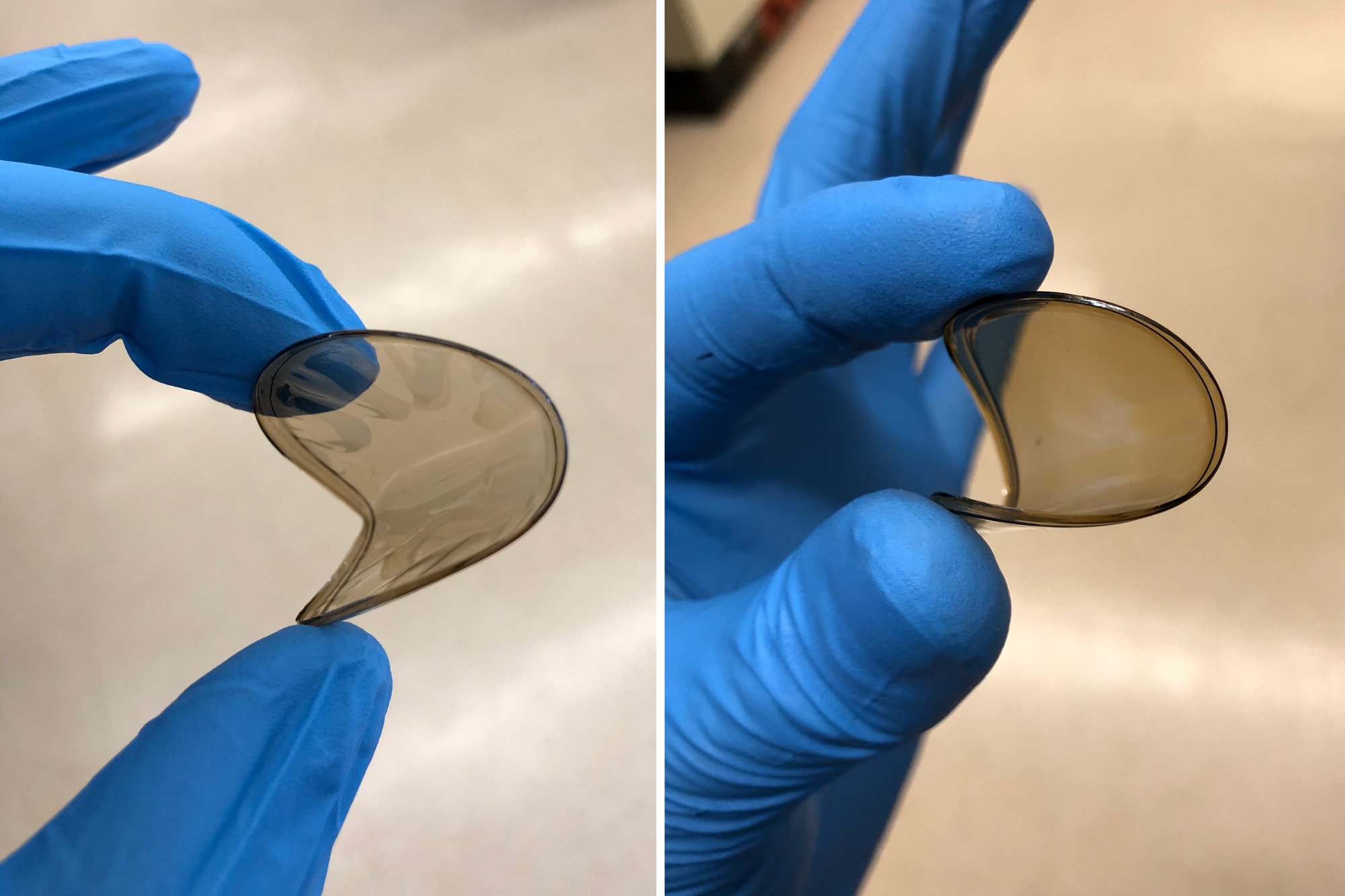

To address this problem, Acoustic Wells is developing an “internet of things” device and an online dashboard to help well owners control their equipment using real-time pumping data.

Mannai, a postdoc in the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics, compared the device’s sensor to a stethoscope. It works via a microphone connected to the pump above the ground. The microphone records the sound of the pump and sends that data to a cloud-based system for real-time analysis. Owners can view that data on a dashboard and send orders to the well to change its pump settings, simplifying the inspection and control processes.

The company has already conducted field tests with an early version of its solution on 30 wells across Oklahoma, Texas, and Louisiana. In those tests, the solution increased production and reduced the failure rates of wells, Mannai says.

The team, which also includes Charles-Henri Clerget, a postdoc in the Department of Mathematics, and Louis Creteur of the company Leanbox, will use the winnings from the $100K competition to develop its user dashboard and continue to scale its user base.

The company is initially targeting owners with at least 100 wells. It plans to sells its sensors with a monthly subscription, charging owners on a per-well basis.

Overall, Acoustic Wells believes its solution could save independent well owners $6 billion annually while preventing the methane equivalent of 240 million tons of carbon dioxide.

Teaching kids to read

T-var EdTech has developed a product called The Read Read that acts as a sound board when blocks of letters are placed on it, in order to mimic phonics, a proven method for teaching children to read.

Phonics has historically required adults to sound out letters and words with children as they read. The process is time-consuming and best done one-on-one. The Read Read allows children to use phonics on their own.

The letters that come with the device represent the major English speech sounds. Children place the letters on the device and, when touched, it sounds out the letters. In the first version of its device, the company has placed braille underneath large, black letters that contrast with the white block to help children who are blind or visually impaired learn braille.

In a pilot with the Perkins School for the Blind, students previously classified as nonreaders learned to read using the company’s device, according to founder Alex Tavares, a graudate of Harvard University’s Graduate School of Education.

The company has begun preselling to parents and schools and has partnered with LC Industries, one of the largest employers of adults with visual impairments in the U.S.

“Phonics works, but it’s not scalable in its current implementation,” Tavares told the audience. “The Read Read scales phonics by allowing kids to practice independently. Finally, phonics is accessible to all kids.”

Wednesday night’s competition was the culmination of a process that began in the winter for semifinalist teams, who received funding and mentoring to develop comprehensive business plans around their ideas.

The event was run by students and supported by the Martin Trust Center for MIT Entrepreneurship and the MIT Sloan School of Management.

This year’s judges were TJ Parker, co-founder and CEO of PillPack; Mira Wilczek ’04 MBA ’09, president and CEO of Cogo Labs; Thomas Collet PhD ’91, president and CEO of Phrixus Pharmaceuticals; Tanguy Chau SM ’10 PhD ’10 MBA ’11, an investor and co-founder of Corvium; and Katie Rae, the CEO and managing general partner of The Engine.

Reprinted with permission of MIT News