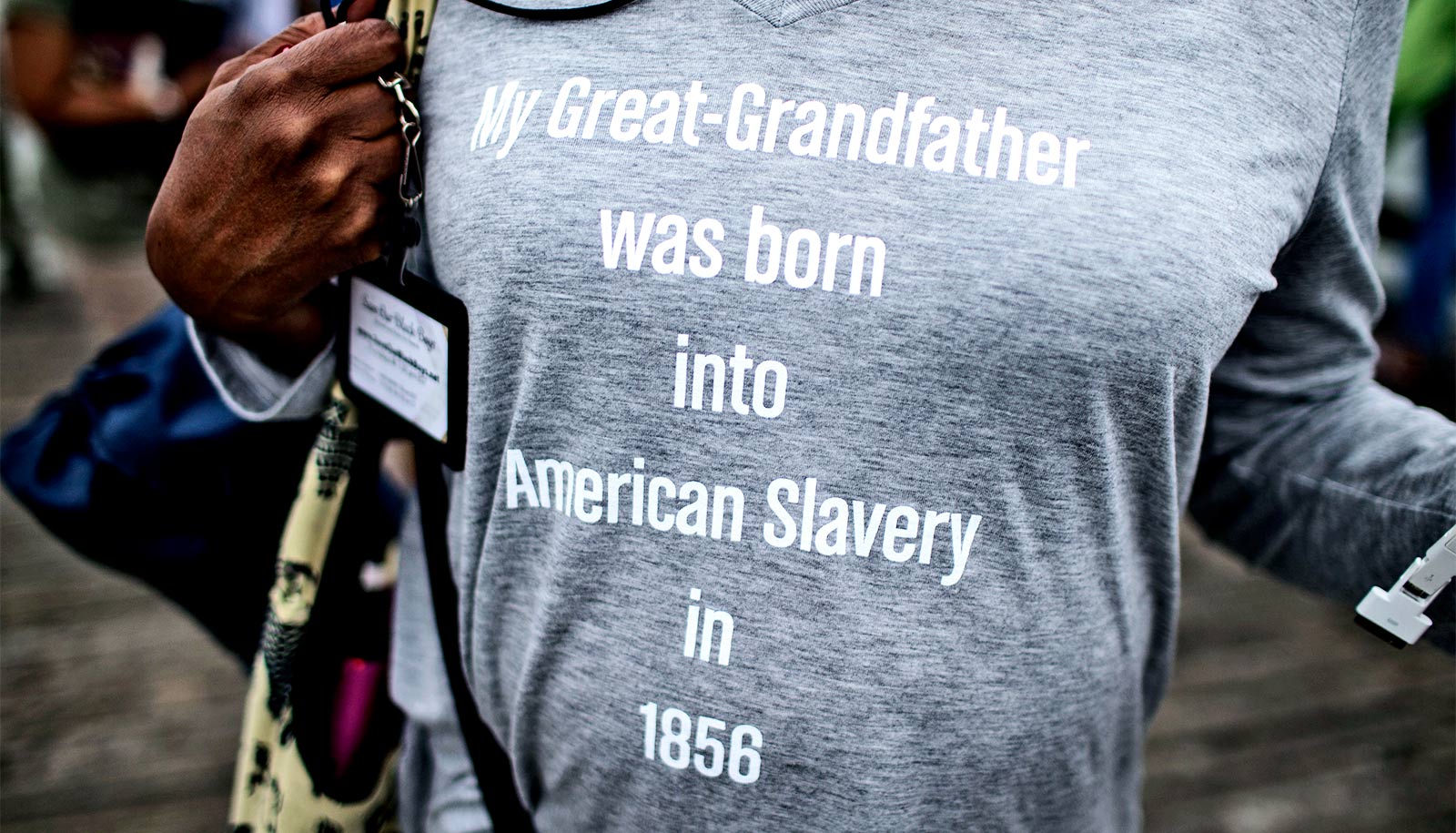

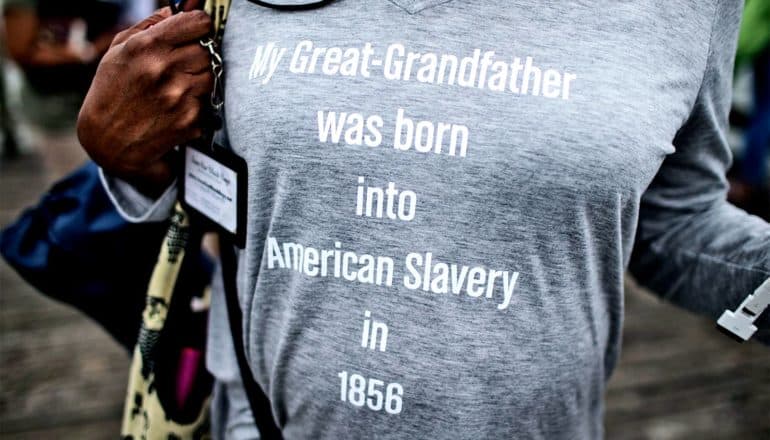

Jacqueline Galloway Blake shows a shirt honoring her great-grandfather during the 2019 African Landing Commemorative Ceremony on August 24, 2019 in Hampton, Virginia. The event marks the 400th arrival of the first African Slaves to English North America in 1619. (Credit: Zach Gibson/Getty Images )

Can historical records change minds about reparations?

"We often think about slavery as old history, as history that's completely disconnected from us. And that's simply not the case."

Historical records could help us move toward more constructively addressing slavery’s legacy in the United States, says journalist Rachel L. Swarns.

“Growing up in Staten Island, New York, I lived just a few blocks away from a convent that ran a bookstore and a community festival that was a highlight of my childhood summers,” recalls Swarns, professor of journalism at New York University and a contributing writer for the New York Times.

“My mother, my aunts, three of my uncles, and both of my sisters were all educated by Catholic nuns. My mother and her family, who emigrated from the Bahamas to New York, even lived for a while on a farm run by Dorothy Day, the founder of the Catholic Worker movement and a candidate for sainthood.”

Yet until four years ago, “when I started reporting on the Jesuit priests who sold 272 people to help keep Georgetown afloat,” Swarns says, “I knew nothing about the priests and nuns who bought and sold human beings.”

Swarns, who is black and Catholic and who goes to Mass with her family on Sundays, researched and wrote a series of stories in 2016 about Georgetown University, the Jesuit priests who founded and ran the college, and their ties to slavery. Since then, she has continued her research, reporting last year on the Catholic nuns who bought and sold enslaved people and the efforts that convents and other religious institutions are making now to atone for their participation in the American slave trade.

“People ask me whether this work has affected my faith. At first, it was astounding to me,” she says. “I soon realized that I shouldn’t have been surprised. After all, the Catholic Church, like so many American institutions, was deeply rooted in what was essentially a slave society.”

Her investigations were a part of a recent wave of public examination of the permanent and deep scar slavery has left on the nation—one that has led to renewed debate over whether and how institutions with historical ties to the slave economy can make amends today.

The topic took on newfound visibility in 2014, when author Ta-Nehisi Coates, now a distinguished writer in residence at the Carter Journalism Institute, authored “The Case for Reparations” in The Atlantic, helping to resurface consideration of compensating descendants of enslaved peoples. Five years later, Coates testified before the House Judiciary on behalf of HR 40, a bill that established a commission to study and develop reparation proposals. In 2016, Washington, DC saw the opening of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, which explores, in painful detail, the institution of slavery and its aftermath.

Today, there is widespread recognition of slavery’s impact in the 21st century. Last year, the Pew Research Center reported that more than 60% of Americans believe that slavery “affects the position of black people in American society today.” However, divisions on racial progress remain, with nearly 80% of black adults believing the US hasn’t made enough progress in giving black people “equal rights”—compared to under 4o% of white adults who feel this way.

The New York Times‘ 1619 Project—a series of essays examining the myriad ways that slavery was and continues to be woven into the American experience—has spawned a podcast, a high school curriculum, and an upcoming book.

Prior to joining the faculty at NYU, Swarns spent 22 years as a full-time reporter for the New York Times, where she served as a senior writer and a Washington correspondent, and became the first African American to serve as bureau chief in South Africa. She later penned American Tapestry: The Story of the Black, White, and Multiracial Ancestors of Michelle Obama (Harper Collins, 2013), which traces the former first lady’s forebears back to the 1800s, identifying, for the first time, the white ancestors in Mrs. Obama’s family tree through archival research and DNA testing.

She is also a coauthor of Unseen: Unpublished Black History from the New York Times Photo Archives (Blackdog and Levanthal, 2017), which unearthed hundreds of powerful photographs that had languished unseen and unpublished for decades.

Here, Swarns explains how using the abundance of historical records can help us move toward more constructively addressing slavery’s tangled web of injustices:

The post Can historical records change minds about reparations? appeared first on Futurity.

Share this article:

This article uses material from the Futurity article, and is licenced under a CC BY-SA 4.0 International License. Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.

Related Articles:

How would reparations for African Americans actually work?

Feb. 24, 2020 • futurityReparations could’ve cut the spread of COVID-19

Feb. 24, 2021 • futurityLinks/images:

- https://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/17/us/georgetown-university-search-for-slave-descendants.html

- https://www.nytimes.com/by/rachel-l-swarns

- https://www.nytimes.com/2016/04/17/us/georgetown-university-search-for-slave-descendants.html

- https://www.futurity.org/frederick-douglass-sheet-music-1916362/

- https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/06/the-case-for-reparations/361631/

- https://www.congress.gov/111/bills/sconres26/BILLS-111sconres26es.pdf

- https://www.futurity.org/national-anthem-racism-1354912-2/

- https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/06/17/most-americans-say-the-legacy-of-slavery-still-affects-black-people-in-the-u-s-today/

- https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/14/magazine/1619-america-slavery.html

- https://www.harpercollins.com/9780061999871/american-tapestry/

- https://www.blackdogandleventhal.com/titles/dana-canedy/unseen/9780316552967/

- https://www.futurity.org/slavery-reparations-records-reporting-2270652/

- https://www.futurity.org